The mass vaccination center at Reggie Lewis is an accessibility success, but a lagging one

In one way, the establishment of mass vaccination centers across Boston took Black organizers by surprise. The vaccine was ready much faster than most people expected. But in another, it felt like Deja-vu. Just like with testing centers, the communities hit the hardest weren’t near the first, or the second vaccination center established.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, government bodies have acknowledged the disproportionate economic and medical affect the pandemic has had on people of color, but Black community leaders say it’s been a struggle to get the City of Boston to adequately address those disparities. The issue of accessibility to services like testing arose immediately as government-run testing sites were set up far from majority-Black communities, where case numbers were highest.

The same pattern with testing center accessibility also emerged with vaccination centers. The designation of the Reggie Lewis Center as a mass vaccination site, a major success for advocacy groups like the Black Boston COVID-19 Coalition (BBCC) — who formed at the beginning of the pandemic to bring the interests of Black and minority communities in Boston to the forefront — didn’t come until the end of February. The lag in accessibility reflected depressed vaccination rates among Black communities of Boston, often attributed to vaccine hesitancy.

At the beginning of the pandemic, even before healthcare professionals understood exactly how the SARS-COV2 virus affected the body, the medical community expressed their fears about how the existing inequities in the healthcare system would lead to worse outcomes for Black patients. In Boston, the neighborhoods of Dorchester, Mattapan, Roxbury and Hyde Park were reporting some of the highest case numbers, but that’s not where the first testing centers were opened.

“People felt like early on there wasn’t enough testing going on for Black and brown people,” said Cheryl Clyburn Crawford, a steering committee member of the BBCC and executive director of MassVOTE. She said she remembers thinking, “if the greatest impact is in Dorchester and Roxbury, why don’t we have testing in those neighborhoods?”

Clyburn Crawford said this initial failure reinforced a historic sentiment of distrust among the Black community in the medical establishment. But as the public health infrastructure was viewed with skepticism, the BBCC’s organizing efforts bolstered trust in their communities. The BBCC collected surplus PPE from schools and construction crews to hand out to essential workers in Dorchester, Roxbury and Mattapan for free and gave out boxes of food and gift cards for essential products to residents.

It wasn’t until the fall of 2020 that city officials took action to acknowledge the mismatch in the pandemic response across communities. Then-Mayor Marty Walsh announced the formation of the Health Disparities Task Force in October 2020, seven months into the pandemic. The task force, a team of 25 religious and business leaders, school administrators and health care professionals, was charged with addressing inequities in health care, testing and data tracking for minority communities in Boston.

Despite the city’s stated focus on disparities, nine months into the pandemic, the positive test rates were still highest in minority communities. So when the conversation turned to vaccination centers, “we thought it odd that the first place you put a mega center was in Foxborough,” said Clyburn Crawford. “The next place you put one is Fenway. When are we going to get it in the heart of where it’s happening?”

The first mass vaccination center, opened on January 18 at Gillette Stadium, is only accessible to Boston residents by car. The second, originally at Fenway Park and later transitioned to the Hynes Convention Center, is accessible by public transit but far from the neighborhoods of Dorchester, Mattapan and Hyde Park.

On January 8, City Councilors Andrea J. Campbell and Ricardo Arroyo ordered a hearing on the already disproportionate vaccine roll out in Boston. The BBCC and city councilors proposed the Reggie Lewis Center as a new mass vaccination center to increase accessibility. “We said put it right here at the Reggie,” said Louis Elisa, a BBCC coalition member. “We as a community fought like hell to get it here 20 years ago.”

As pressure from BBCC members and national figures like Representative Ayanna Pressley mounted, the city announced a mass vaccination center would open at the Reggie Lewis Center in Roxbury, right next door to the first testing center accessible to minority communities.

Hesitancy or Inaccessibility?

Once the mass vaccination site in the Reggie Lewis Center opened on February 27, it was time to convince people to use it. The BBCC sprang into action once again.

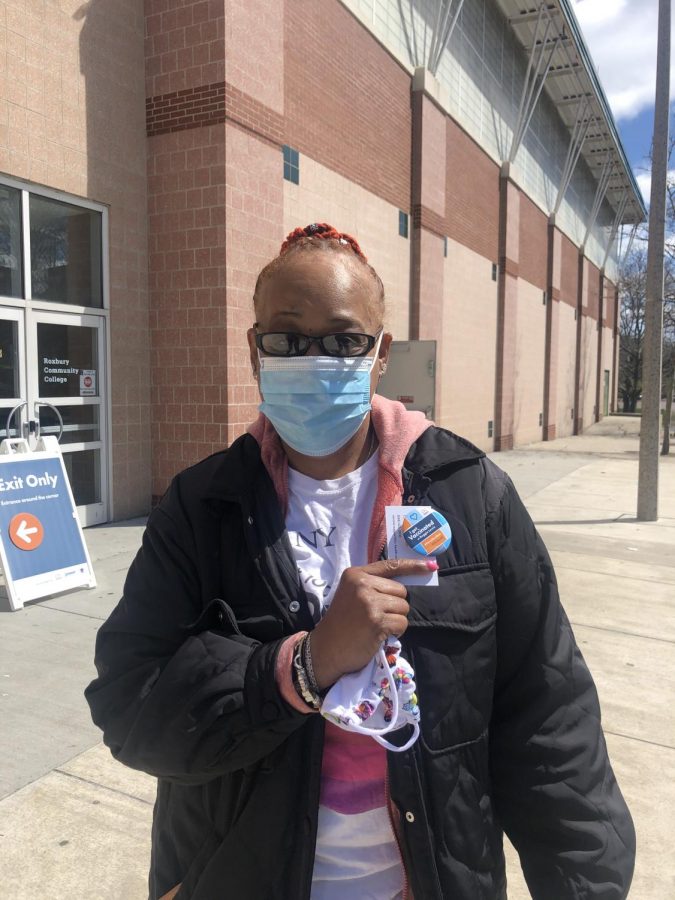

“If you asked me a while ago, I would have said ‘I’m not getting it,’” Stephanie Sims said as she exited the mass COVID-19 vaccination center at the Reggie Lewis Center after receiving her second dose.

“I had to stop listening to the craziness. I had to say, ‘this is about my health,’” Sims said. She plans to see her grandchildren in person and finally visit her mother in Georgia.

“Over a period of a month and a half we had townhall meetings Saturdays from 4 to 6 p.m.” Elisa said. The BBCC brought in Black and Latinx health care professionals to answer questions about testing and vaccination. They also established an outreach team to go into communities, specifically targeting barber shops, beauty parlors and churches, to educate residents on their vaccination options and pass out literature in nine different languages.

Part of the proposal for the Reggie Lewis vaccination center included setting aside a portion of the appointments so community outreach organizers could make on-the-spot appointments for people they reach. Elisa said the ability to secure an appointment within two to three days of outreach makes a difference for residents’ willingness to go. And, he said, the rate of missed appointments is between 6%-12%, less than the state average.

“The BBCC has never really pushed people to get the vaccine,” said Clyburn Crawford. “Our job is to make sure people know how to access it.”

As vaccines have become more accessible to minority communities in Boston there has also been a shift in the national data on vaccine hesitancy. Data released by the Kaiser Family Foundation revealed that white evangelicals and Republicans are now more likely to say they will “definitely not” get a vaccine against COVID-19 than Black or Hispanic respondents.

The KFF also stated that Black respondents reported more difficulty accessing the vaccine. But overall enthusiasm continues to grow across the board as appointments open up to more age groups, scheduling websites improve and more people see their relatives and friends getting vaccinated.

Like Sims, Clyburn Crawford was initially one of the skeptics. “Back in December I clearly stated I was not having this vaccine,” she said. There was a level of mistrust because of how the testing roll out occurred, but she came around as the BBCC education efforts continued and the prospect of receiving the vaccine became real. “I wanted to see my family.”

Clyburn Crawford said the success the BBCC has had with community partnerships and outreach should be a model for governments in the future. “A week prior to us starting our outreach, Massachusetts was 42nd in the country for vaccination of Black people. Right now, they’re at number 2 or 3.”