A summer heatwave could hurt Boston neighborhoods already suffering from COVID-19

Dorchester and other urban communities tackling the spread of coronavirus may have to deal with extreme heat in coming months

As summer approaches and the social distancing measures necessitated by COVID-19 continue, Bostonians who lack consistent access to air conditioning in their homes face additional challenges and health risks.

July 2019 was Boston’s hottest month on record, with a dozen days of high temperatures over 90℉. A similar heatwave this summer could pose serious health risks.

According to the CDC, heat-related illnesses include heat stroke, dehydration and cramps. Senior citizens, young children and people with disabilities or pre-existing medical conditions may have a greater health risk. Prolonged exposure to extreme heat can reduce cognitive functioning and worsen existing cardiovascular and respiratory issues. In the worst cases, it could even be deadly.

“If we’re still in lockdown mode, and you can’t go outside and your house is hot, there’s going to be a lot more … health issues, mental health issues, physiological health issues, people with heart conditions or breathing conditions or asthma are all going to have problems,” said David Queeley, the director of eco-innovation of the Codman Square Neighborhood Development Corporation in Dorchester. “It’s not just a COVID issue. It’s a climate issue.”

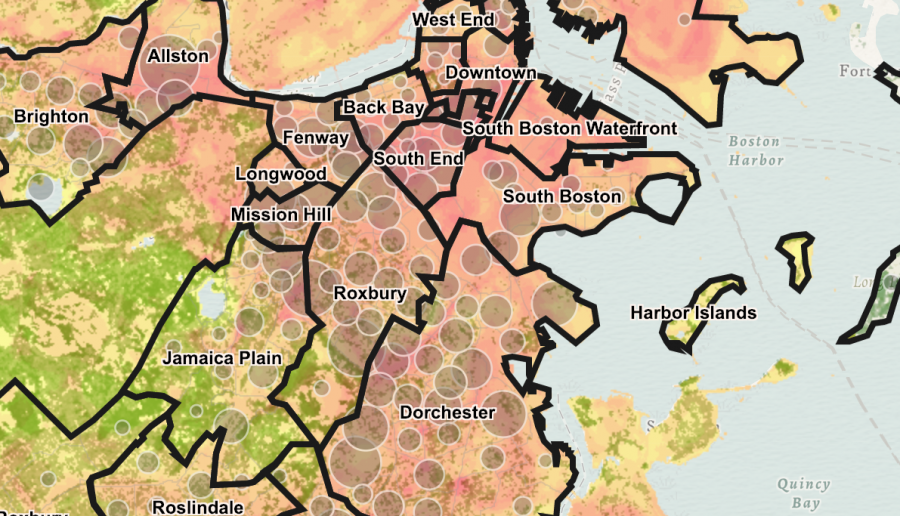

Summer heat is exacerbated by the urban heat island effect, when dense city areas made of concrete, asphalt and other heat-absorbing materials trap daytime heat, which lingers through the night. Without much green space or coastline to offset some of the heat and bring down temperatures, Boston’s inland neighborhoods – particularly Dorchester and Roxbury – can broil 24 hours a day.

These two neighborhoods are home to some of Boston’s most vulnerable residents. According to city data, Dorchester and Roxbury are among the neighborhoods with the highest populations of people of color, recent immigrants and people with low-to-moderate income. Residents may not be able to afford the energy costs of cooling their homes for long periods of time.

What’s more, Dorchester and Roxbury do not have many air conditioned public spaces where residents can cool off during heat waves. Though there are some commercial locations, like supermarkets and shopping malls, these are no longer freely accessible due to COVID-19. With a summer likely to be spent mostly indoors due to the pandemic, community organizers and city officials are working to find ways to help residents at greater risk for the impacts of extreme heat.

The City’s plans to keep cool

The City is working toward long-term goals of climate preparedness for vulnerable neighborhoods through its program Climate Ready Boston, launched in 2014. This includes planning for policy and green infrastructure guidelines that will address issues related to flooding due to sea-level rise and increased storm events, stormwater management and heat.

In the 2019 update to Boston’s Climate Action Plan, which sets goals for how the City will adapt to climate change, Mayor Martin Walsh wrote, “As we reduce emissions and prepare our communities for the impacts of climate change, we must place people first. This means designing and implementing policies for and with communities of color, low-income neighborhoods, youth, older adults, women, people with impairments, persons facing homelessness, and people with limited English proficiency.”

Yet Queeley said that many of Climate Ready’s efforts so far have gone to more affluent areas, along the coastline which tend to be less affected by the urban heat island effect and are more prone to flooding.

“Most of the energy [from Climate Ready] has been focused on coastal areas, but not so much in inland areas where heat is an issue,” Queeley said. “There have to be policy changes too, so there are cooling centers and resilience centers for people to go to in an emergency or a heat emergency.”

Since its founding, Climate Ready has prioritized the development of neighborhood-specific coastal flooding plans as a climate issue of immediate need, including one for Dorchester, which launched in fall of 2019. Climate Ready is also developing heat-related plans for Dorchester and the rest of the city.

The City also aims to engage people about adapting to climate change through Greenovate Boston, a program, launched in 2014, that works with residents to become leaders for climate action within their own communities.

Last fall, Greenovate began a series of in-person meetings to bring city officials and residents together to discuss racial and gender equity and brainstorm potential climate solutions, including measures to counter extreme heat.

“We understand that there’s a great immediacy just because the impacts are already being felt and they are already affecting certain communities versus others,” said David Corbie, the Greenovate Boston outreach manager. These meetings help city officials, including Climate Ready Boston, understand “those lived experiences and those stories from the community members, which then will fuel a lot of the work in terms of programs and policies.”

In addition, Greenovate has used an interactive map and an assessment on vulnerable areas from Climate Ready Boston to help residents understand the population data and climate factors that impact their communities.

Local groups gear-up for the heat

Neighborhood corporations that serve inland, urban neighborhoods in Boston have already begun conversations around heat preparedness for more vulnerable residents.

Codman Square, along with the Dorchester Bay Economic Corporation and the Southwest Boston Community Development Corporation, formed a grassroots climate justice initiative, called Fairmount Indigo CDC Collaborative, which began meeting in-person in early March.

Queeley’s organization, the Codman Square Neighborhood Development Corporation, works with residents in Dorchester around issues of urban development, affordable housing and climate preparedness. This includes converting portions of sidewalks into grass areas and working with the city to plant more street trees.

Because of COVID-19, organizations like Codman Square have suspended in-person group meetings and limited door-to-door services, which might reduce their impact.

Now with the summer approaching, the climate justice members are continuing their meetings using Zoom.

“There’s no replacement for having face-to-face meetings,” said Queeley. “There’s an energy and a desire to move forward. We were going to do it anyway. But now it’s great to hear feedback from people who want to meet via Zoom, and get out there and do something around climate.”

Read about how we’re covering COVID-19 and our sustained commitment to telling stories of hope, justice and resilience.

In Roxbury, neighborhood organizations are also adapting to fit residents’ needs during the pandemic. Madison Park Development Corporation is a nonprofit based in Roxbury that provides residents with programs related to nutrition, affordable housing, financial literacy, educational and work development and health and wellness resources. Typically, these events are held in the development corporation’s air conditioned buildings, but those spaces are now closed indefinitely due to social distancing.

Before the pandemic, the development corporation hosted art and theater events at Hibernian Hall, which has air conditioning. During a heat wave, their organizers would stay in contact with residents, many of whom are of older age, through phone checkups and delivering care packages, which included water and informational letters about ways to stay healthy through the heat.

But now, with public centers closed, staff at Madison Park are concerned about residents’ access to hand sanitizer, cloth face masks, food and water.

To cope with these challenges, Madison Park’s resident service coordinators have begun delivering supplies and checking up on residents regularly by phone. They also provide updates on the latest news regarding COVID-19, as well as guidelines on how and when to practice social distancing.

“We are doing 80-plus deliveries a week now, on a regular basis, making sure residents have their medications and their needs” said Leslie Stafford, an organizer at Madison Park. “The resident service coordinators distribute water, snacks and make sure things go round that [residents] have paper towels, water, all the cleaning tools.”

Although there is not yet a specific plan to deal with summer heat, Madison Park staff is determined to find a sustainable solution.

“Resident service coordinators have a good relationship with the residents and talk to them about what is needed,” said Javier Gutierrez, Madison Park’s director of health equity and resident engagement. “We want [our communities] to be physically isolated, but there’s no reason why they need to be socially isolated.”

A heatwave and COVID-19

During public health emergencies, including those related to heat as well as the current pandemic, the Boston Public Health Commission leads the city response in disseminating health and safety information and resources to residents.

Last summer, during the heat emergency in July, the city response was led by BPHC and included opening Boston Centers for Youth and Families community centers and pools to the general public, along with providing ways to stay healthy through the heat and multilingual fact sheets.

While the Scope reached out to the BPHC, they were unable to comment as they are exclusively dealing with emergencies related to COVID-19.

However, if the pandemic continues into the summer, opening public centers for heat relief while maintaining social distancing guidelines could pose new challenges, particularly to inland, urban communities with few ways to escape the heat.

Recently, the pandemic has affected communities, primarily residents of color and multilingual residents. In April, City Councilors At-Large Michelle Wu and Julia Mejia and District 5 City Councilor Ricardo Arroyo began planning for an equitable recovery for these communities.

“We could see this coming. And it’s awful and infuriating to know that communities who have been facing so many crises before are the first to suffer during this unexpected new crisis,” said Wu. “The huge mobilization of resources to try to stop and fix this pandemic needs to be accomplishing some of our other long-standing goals too, of really building sustainable resilient communities for everyone, so that next time this happens, whether it’s another public health pandemic or a natural disaster or extreme weather event, that we are ready and that people are able to continue to live and grow in their communities.”

Greenovate and Climate Ready Boston officials recognize that residents who were already the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change are also impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. These city organizations have been meeting digitally with neighborhood corporations and community leaders, including Queeley, for preliminary planning discussions about how the city and communities can coordinate relief efforts in the event of extreme heat emergencies within these inland urban neighborhoods.

“We should be using the disparities that this crisis has shown us to really say, ‘Let’s just do something. Let’s do things in a different way … from the ground up really to address the issues of citizens who have been disenfranchised for years,’” said Queeley. “It’s an environmental justice issue. It’s an equity issue. It’s a race issue.”