Cold air poured through the windows of my parents’ 1996 Toyota Corolla. I sat in the back seat, arms outstretched, intoxicated by the crisp breeze as 50 Cent’s “In Da Club” pumped through the car’s speakers, sending vibrations up my 7-year-old forearms.

The year was 2003, and this was one of my first distinct hip-hop memories.

Author Tim Foley as a child (left) and then in 2017 (right).

50 Cent was from Jamaica, New York, about a 20-minute drive from where I grew up. When I was a kid, it was never too hard for me to think of a rapper who came from nearby. My friends wore Rocawear clothing to school – a brand started by Brooklyn’s Jay-Z. Everywhere you went, you would see murals honoring artists like Biggie Smalls or Big Pun (from Brooklyn and the Bronx, respectively).

A decade after that back-seat vignette, I moved to Boston, and I had a feeling it was going to be different. I had never heard of any rappers from Boston before. What kind of a place was I going to? Was there even hip-hop in Boston?

Five years into my time here, I’m still an oblivious New Yorker, but I finally set out for answers. A lifelong Bostonian helped to put it in perspective.

“We have more talent, at multiple levels, than we’ve ever had,” Dart Adams said, referring to Boston’s rap scene. Adams is a South End native who has taken on the role of mentor for many of the city’s up-and-coming emcees. He is a hip-hop writer and historian who has a lot of influence on the community level.

“It’s to the point now where people would ask me, ‘Who would you feel comfortable putting on a bill with national acts?’ And I could just run off a list, and I would have to write it down and recite it to them because it’s that many people,” Adams said. “I’d throw Latrell James on with anybody. I’d put Dutch ReBelle on with anybody. I have no problem with putting [Troy] Ave on in front of anybody.”

Still, I was left with a number of questions: How is it possible that all of these artists have been grinding on with their careers, consistently putting out excellent music this whole time, while somehow still flying under the radar? What forces are at play here that are preventing them from becoming household names? And what needs to happen in order to set the opportunities in place to change this?

“There’s not yet a Boston Meek Mill,” said Brendan McGuirk, making reference to the rap sensation that sprung out of Philadelphia’s underground when he signed to Rick Ross’ Maybach Music Group label in 2011. McGuirk is a freelance journalist for Metro Boston, specializing in culture and entertainment, and he talked a lot about a theme that plays a central role in this conversation: stigma.

This is definitely part of why we don’t hear about Boston’s hip-hop scene. There is a clear reputation here, and rappers probably don’t want to be associated with it.

“When people say ‘Boston,’ people think of sports teams, they think of Southie, and they think of white guys with accents,” McGuirk said. “That’s like a really pervasive and strong iconography. And of course, there’s a tremendous amount of erasure in that image … so as it relates to the music scene, in some ways I think it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

“How you gon’ lie about the place that you’re from?”

Back in 2003, a laundry list of Boston emcees collaborated to put out a song called “Home.” Under the collective name, “Kreators,” legends like Guru, Ed O.G., and Akrobatik graced the track, along with a bunch of less-known artists like Big Juan, who posed a relevant question in the first line of his verse. The lyric hits close to home when we talk about this issue of regional representation:

How you gon’ lie about the place that you’re from? / The house you grew up in, / The block that you hung?

Murray Forman, a Northeastern professor and renowned hip-hop author, shared the song with me.

“In that track, ‘Home,’ there’s that line where they sort of say, ‘This ain’t just a college city – things are real in the streets,’” Forman said. “Boston’s reputation is a lot of things, and they really are deeply sedimented. But it’s not a hip-hop city – hip-hop has always had to play second fiddle or take a back seat to these other initiatives that Boston does have a strong reputation for.”

Let’s take a moment to step back and unpack some of the origins of Boston’s reputation. A good place to start is in 2017, when “Saturday Night Live”’s Michael Che called Boston the most racist city he had ever been to. The comment sparked widespread conversation, and even received significant coverage when The Boston Globe’s Spotlight Team dove into some investigative reporting about the city’s history.

“Boston’s reputation is a lot of things, and they really are deeply sedimented.”

Che’s sentiments were certainly legitimate. Boston has always had a regrettable relationship with its residents of color, and it is important that the city be held accountable for that.

McGuirk said that Che’s critique of the city was fair – the Spotlight piece lists Boston as 73 percent white; significantly more than the other nine major U.S. cities noted in the graphic. But McGuirk added that the idea that Boston is a “white” city only maintains the lineage of white supremacy by reinforcing the invisibility of communities of color. I believe this is part of why Boston’s hip-hop is not talked about – many of the artists here are hesitant to identify with that imagery.

In fact, a lot of the Hub’s hip-hoppers end up deciding to pack their things and move elsewhere. Adams told me about “Bos Angeles” – a phrase used to describe a growing collective of Boston rap acts that have relocated to the West Coast.

Millyz is a local artist who changed location, in his case to New York, and he fervently self-identifies with Cambridge rather than Boston. He made an appearance on New York’s prolific “Funk Flex” radio show to kick a five-minute freestyle, during which he shouted out “617,” “978” and “508” – three area codes associated with the Greater Boston area – but did not once utter the proper noun “Boston.” Instead, he mentioned touring in San Diego and smoking on “California recreation.”

Millyz (above) identifies as a rapper from Cambridge instead of Boston.

Another example is Joyner Lucas, a very successful rapper from Worcester, Massachusetts, who last year released his album “508-507-2209.” Though the title is a clear reference to the locale, Lucas made no mention of the proximity to Boston throughout the 16-track project.

“Artists that came from Boston and blew up and moved to L.A. – they’re not going to say anything about Boston until they have to do a Boston show,” said Lakiyra Williams, a slam poet and rapper from Roxbury who goes by the artist name Oompa.

To me, this reveals artists’ aversion to linking their names with the city of Boston. It’s similar to my dad’s insistence that we’re from Queens, not Long Island, even though we’ve always technically lived two minutes outside of Queens’ border. Something about Long Island’s reputation deters my dad from calling it home – he doesn’t want us to be seen as snooty white folks who spend all of their time on the beach. It’s certainly fair for him to not want that association, but it’s based on another troubling example of regional iconography that denies the existence of all people of color that live in the area.

In Boston, this unwillingness to self-associate leads to a lack of exposure for the city, and it creates a disadvantage for local rappers who are still trying to break through. When artists leave Boston, it diminishes the support system that exists within the city itself.“I wish that, like for example, Cousin Stizz, looked back and was like, ‘Who’s the next artist coming out of Boston? Let’s reach out to them. Let me get them,’” Williams said.

Cousin Stizz is maybe the hottest name coming out of Boston today. Although he grew up in Dorchester, he moved to Los Angeles after signing to RCA Records. “But more than I need those artists to think about Boston artists now, I need the people that drove them to Los Angeles to realize that people are moving to Los Angeles.”

Before blaming Boston’s artists for not showing enough support to their home, it is important to look at the factors that forced them to leave in the first place. This brings me to the other stigma at work here – the one associated with the music itself.

Hip-hop has been historically viewed as a black art form, and because of that, people have always fed into all kinds of narrow-minded assumptions about the music. Chris Faraone, editor of DigBoston, talked about the discrimination that hip-hop has faced in the Hub.

“I wrote the first big story about this … in 2005, there really was nowhere to have hip-hop shows,” said Faraone, who ruffled a lot of feathers with his expository piece for DigBoston, which was called The Weekly Dig at the time.

“It’s not just live shows that were thrown out … this also applied to DJs downtown playing hip-hop music. And the way that they did this was that the police told clubs that if you have a club, you have to hire a police detail to watch outside the club. It’s really a backhanded way of them saying, ‘You’re not going to be able to do it.’”

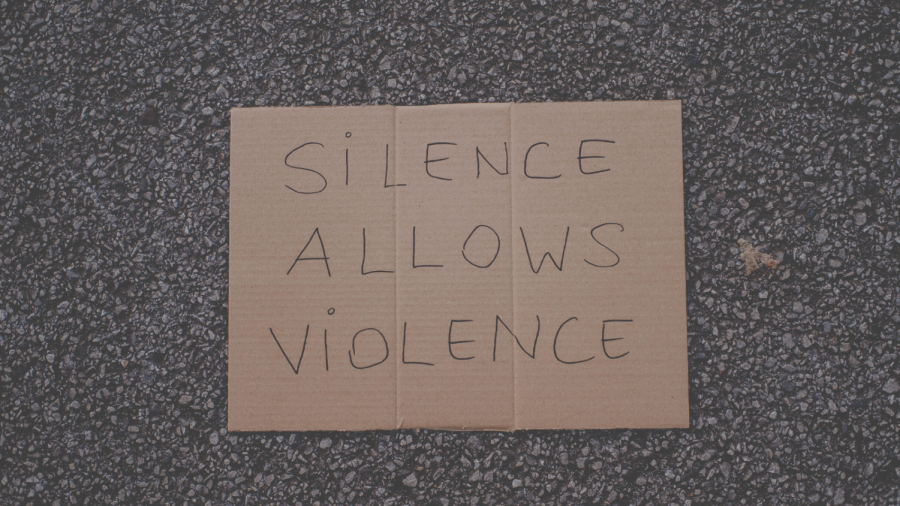

The demand for heightened security is based entirely in the idea that hip-hop crowds are more violent than other crowds.

“The truth is that, there’s no fucking statistics on these things so it’s just hunches,” said Faraone. “It’s a ridiculous thing … This is definitely racist, and in my experience complete bullshit – that hip-hop shows are more violent. I just don’t believe it.”

I believe that Faraone is right, and that this unfair representation of hip-hop acts is part of the reason there are disproportionately few venues in Boston that are willing to host shows.

Amelia Mason wrote an article for WBUR.org back in February titled “Is Boston Hostile to Hip-Hop?” that took a look at this very issue. Mason highlighted a number of artists who had been turned away by venues that “don’t book hip-hop,” citing security concerns as the main reason.

“The truth is that, there’s no fucking statistics on these things so it’s just hunches. It’s a ridiculous thing. This is definitely racist.”

DigBoston Editor Chris Faraone on the lack of Boston venues willing to host hip-hop shows

Lisa Finelli is the founder and CEO of Xperience Creative, an organization that has worked to promote hip-hop acts in Boston since its inception in 2015. According to Finelli, who worked in New York before coming here, Boston venues show a lot more concern about the “type of crowds” that hip-hop shows bring in. She echoed some of Faraone’s ideas about discrimination.

“I think racism plays a huge issue when it comes to booking hip-hop shows,” Finelli said. “There’s some of the smaller venues where a rock show is like, ‘Come on in,’ and a hip-hop show is like, ‘I’m going to look through your bags, here’s a [metal detector] wand, here’s this.’… I wish there was a little bit more respect in both directions.”

In the nearly 50 hip-hop shows that Xperience Creative has promoted, Finelli said only one fight has taken place. She said that security removed the person right away and that was the end of it. But despite the overwhelming peacefulness of these events, Xperience Creative will often not be asked to come back for another show.

Finelli cited a spoken word event that lost a venue’s support despite positive reception from the audience. She declined to say the name of the venue, for “legal purposes.”

“I can definitely say that there was an event that I did that was well-received, and the venue manager was not happy with the choice of words that my poets were using,” Finelli recalled. “I can’t help but think there’s a bigger thing there. If you’re allowing rock artists and metal artists and grunge artists to say whatever they want, what is the difference between a spoken word poet getting on stage and saying whatever they want?”

Finelli and Faraone’s arguments are absolutely valid. Given Boston’s history with racism, and given America’s history with hip-hop, there is no doubt that an ingrained tone of racial prejudice underlies a lot of the hostility the music faces. Williams agreed that racism plays a major role in all of this, but she also pointed towards classism.

The fact is, there are only a few venues in Boston that support hip-hop, and of those, even fewer will allow artists to perform without covering the costs for the event. Artists will have to sell tickets themselves to raise the money to pay for their events, or otherwise dish out the funds for it in order to be allowed to perform.

This “pay-to-play” platform, as it is colloquially called, ends up creating a jarring disparity in access, so that the opportunities always go to artists with more money. It robs up-and-coming acts of the chance to kick-start their careers, while keeping the power and influence in the hands of artists that already possess societal pull. It is an unfair system, and it does nothing to promote a sense of community.

Finelli said that even for local acts, it is much harder to find bookings in Boston than in other East Coast cities like New York, Baltimore or Philadelphia. She said that in other cities there are far more opportunities for hip-hop artists to be paid perform, or at least be able to perform without funding the cost themselves. This further reinforces the incentive for artists to leave Boston; it’s simply not profitable to stick around.

“One of the biggest issues in my eyes is that because of the lack of support for the artists, the labels, nationally, don’t take this market as seriously.”

Lisa Finelli, CEO and founder of Xperience Creative

Xperience Creative doesn’t subscribe to the pay-to-play model, and will not do business with venues that do. This narrows the already limited options for bookings in Boston. For instance, the Middle East nightclub in Cambridge is arguably the most prominent location for hip-hop shows in the area, but because it operates pretty much exclusively as a pay-to-play venue, acts promoted by Xperience can’t perform there.

Ned Wellbery, the CEO of Leedz Edutainment, is now also The Middle East’s booking manager. He downplayed the role of the venues in all of this, saying that the increasing commercialization of Boston’s hip-hop radio stations (if they deserve to be called that) and the general weakness of the city’s music industry are more responsible for the comparatively small hip-hop scene.

It’s true – JAM’N 94.5 and HOT 96.9 simply don’t cut it as hip-hop stations. I deduced this after about two weeks of listening while driving around Boston for my first job. Adams agreed with this as well, and he can speak on a far broader data sample than my six months of commuting:

“Here, we have stations that are stop gaps,” Adams said. “There’s JAM’N 94.5 – but it’s not an urban radio station … by any long shot. I don’t know why people keep thinking it is. We have HOT 96.9, but that format – even though it plays what some people would call ‘urban radio’ – it doesn’t cater to the same demographic.”

All that considered, I am not convinced that with today’s streaming platforms, radio has enough pull to be held wholly responsible for the injustice here. It doesn’t let the venues off the hook for racism or classism, and neither does the small size of Boston’s music industry. Let’s not forget – we are still talking about the city that gave birth to the likes of Aerosmith, the Pixies and The Cars. Boston’s rock and pop industries have yielded plenty of superstars. Why have hip-hop artists in the same city struggled so hard to attain that level of acclaim?

Finelli offered a strong reminder that the relationship between a city’s music industry and its venues is actually quite symbiotic.

“One of the biggest issues in my eyes is that because of the lack of support for the artists, the labels, nationally, don’t take this market as seriously,” she said. “It’s not always an ‘A’ market, you know, sometimes this market is B-listed.”

If Boston’s music industry is not thriving, the venues must be held accountable for that as well. This is not a one-sided issue, and there is no way to address it accurately without acknowledging the matters of discrimination that are at hand here.

Like cars to a plane

It’s no secret that Boston is segregated. Take a walk through the South End and into Roxbury; take a look at the faces. Look at the grotesque economic disparity – you see lavishness juxtaposed with destitution, rattling instances of gentrification, transplanted college students waiting at crosswalks next to weathered townies.

The city is a great bustling contradiction, and over time, this dynamic has created an atmosphere of tension. When we talk about the challenges faced by hip-hop artists, we are also talking about an overarching opposition to change held by those in the city who have long been in control. Boston’s hip-hop scene, for all intents and purposes, is stifled by wide-reaching disparities in opportunity and access.

“Hip-hop is about survival and is about resistance at its core.”

This means that any realistic process of change must start with concerted efforts to close those gaps. According to Williams, that’s the essence of hip-hop to begin with.

“Hip-hop is about survival and is about resistance at its core,” the Roxbury wordsmith said. “At the end of the day, the closed doors, I think, are about the way that people with money and power and resources look at hip-hop … And in turn, what they’ve done has disenfranchised the people who in Boston have been invisible anyway.”

Williams is one of the artists that has been working to change that through the power of the music itself. Her next show in Boston is on April 27 at Great Scott, and she is promoting the show through “a grassroots guerilla marketing campaign … to really highlight how Boston artists can sell out shows in their own city (that consistently holds them back),” according to an email from her manager, Amelia St. John.

In terms of confronting inequity, progress is slow, but it has to begin with small initiatives like these. Williams is also working with a digital media production company called HipStory, which is “dedicated to centering marginalized identities in media through music and film.” HipStory represents a number Boston’s hip-hop artists, helping to promote their work and curate events. This offers a lot of the support that is generally lacking for artists in the Hub.

“None of this is the artists’ faults,” said Marquis Neal, who helped to create the New Era of New England (NEONE), another organization that helps musicians gain access and exposure.

He asked me if I could name any groups I knew of, other than NEONE (pronounced, ‘anyone’) that were actively promoting hip-hop. I listed off Leedz Edutainment, Xperience Creative and HipStory. Then he asked me if I knew of any (other than Leedz) that had been in existence for more than five to 10 years.

I didn’t.

“Exactly,” Neal responded, “That’s the problem. The people that you’ve mentioned – these are people that are part of the change that is happening. We’re on the cusp of change, but prior to this last two years, there was nothing.”

Like Xperience Creative, NEONE works to make sure that hip-hop artists are being paid to perform rather than paying to play. Neal, along with Chimel Idiokitas and Steven Foley, provide mentorship for up-and-coming artists, catering to their individual needs. NEONE’s flagship hip-hop show, “The Pull Up,” had its third installment last month at ONCE Somerville, and it was a great success.

This dedication to artist development is crucial, and the mission of NEONE needs to be widely embraced in order to build up hip-hop culture here. I spoke with Jared Bridgeman, a Dorchester-born rapper better known by his artist name, Akrobatik. Twenty years deep in his hip-hop career, Bridgeman continues to put out music, while also teaching at University of Massachusetts Boston. He spoke about a generational rift that exists between artists in the city.

“I was 15 in 1990,” Bridgeman recalled. “You could go to, maybe, your local community center and find places to like, join up with break dance crews or learn from one of the older kids how to DJ and stuff like that. So, I think that there was nothing but opportunity.”

But as time has passed, that type of apprenticeship has waned, and Bridgeman said that support for young artists from the local community is not what it used to be.

“If you’re talking about, let’s just say 16 to 25-year-olds – depending on what level of guidance they have coming into it, they might just be coming in from scratch,” the emcee added. “If anything has devolved, it has been the appreciation for the culture itself.”

Bridgeman is one of the artists that is trying to change that. Williams named him and local lyricist Moe Pope as two mentor figures who continue to give back to Boston and bridge the generational gap.

Hip-hop is about community. It is about providing a voice for the voiceless, and opportunities to those that have never had them. In order to resolve the cultural tension in Boston, people are going to have to start overlooking their differences and working together. Only then will hip-hop be given the platform it deserves.

“I’ve been on a plane the last three or four days, going different places, and I looked out the window one day and I thought about the hip-hop scene in Boston,” Williams said. “When you’re in a car… you look at all the cars passing, and all of, like, the intersections and the highways and people passing. But when you’re in an airplane and you’re looking down, you really can’t see – you just see a bunch of cars moving, you don’t know anything specific. And I think of us in Boston as the cars.”

Perhaps that was me in the airplane, as I packed my bags to move from New York to Boston five years ago. All I can say is that I’m grateful to have been able to see the cars up close. To hear the diverse roar of the beautiful, complex engines, and to breathe in the burnt rubber. As I sat in the back of my parents’ 1996 Corolla, I had no idea how high up I was. But now that I know the magnitude of work that Boston’s rappers have been putting in, I desperately want to see them provided with the vehicles to elevate.

“Boston is a city that sleeps,” Adams said. “But I think that there’s going to be less and less resistance when people realize that you can do shows – you can do events here and you can make money – to begin … we need to close the gaps and inequity in terms of venues and spaces.”

Tim Foley is a 2018 graduate of Northeastern University’s School of Journalism and is now working as an educator in Washington, D.C.