Advocates continue to urge the public to provide better support for people experiencing domestic violence

November 12, 2021

Domestic violence is all around us, whether it affects a coworker, a family member, a friend or even someone you pass walking down the street. It is unavoidable and has become increasingly prevalent during the coronavirus pandemic, suggests a survey conducted by researchers at the University of California, Davis.

1-in-4 women and nearly 1-in-10 men have experienced contact sexual violence, physical violence and/or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime, according to the CDC’s National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS). The fight to end domestic violence faces many challenges, including the lack of resources for victims, the difficulty in educating people about power dynamics and the gender and racial disparities within domestic violence.

“When people say to me, ‘I don’t know anyone that has been affected by domestic violence,’ I explain to them that usually means that no one has chosen to tell you yet,” said Greta Hagen, the director of philanthropy and engagement at RESPOND Inc.

RESPOND, Inc is New England’s first domestic violence prevention agency, providing a domestic violence shelter, a crisis hotline, support services, training and education to those in need.

The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence defines domestic violence as the “willful intimidation, physical, emotional, or sexual assault and/or other abusive behavior as part of a systematic pattern of control perpetrated by one intimate partner against another.” Domestic violence in the form of gender-based violence is one of the most pressing issues women face today, said Hagen.

Many might ask questions like, “Why doesn’t she just leave?” but questions such as these ignore the actualities of domestic violence. Associate Professor Margaret Drew of the University of Massachusetts School of Law, who has been practicing in the field of domestic violence since 1981, addressed this question.

Abusers use tactics to trap their victims. The abuser uses “isolation and financial control, so the [person experiencing] domestic violence comes to the mindset that they won’t be believed [and] that they are not credible [or] competent on their own,” Drew said.

The abuse goes way beyond physical violence or monetary dominance. Abusers often use children as leverage to continue the abuse. “If children come into play, often the victim will not leave their abuser to protect the kids involved and because they fear losing their parental rights,” said Drew.

Drew maintained it is essential to shift the perspective in how people view survivors of domestic violence. She said we must attempt to understand that most victims do not believe they are making unsafe choices.

People experiencing domestic violence often face daunting and impossible alternatives: stay in an abusive situation or risk losing everything in life they’ve grown accustomed to.

As stated by Drew, misogyny plays a key role in the survival of domestic violence today. There is a continuous lack of conversation around misogyny and sexism’s role in our society. Drew warned of a new wave of misogynistic ideals within media, culture and the executive branch of government.

“When Trump was elected in 2018, we elected misogyny,” Drew said.

Misogynistic language has become deeply embedded in modern-day culture, making it difficult for survivors of domestic violence to confide in others, report their abusers and get the help they need because society has been conditioned not to believe survivors.

Survivors are not believed because there are strong connections between these normalized daily behaviors, such mild harassment or passive aggressive comments, that women brush off and the more serious abuses. Therefore, “when a survivor is finally able to find their way out of the relationship, it’s essential that those they confide in believe their story,” said Drew.

Jessica Loftus, a social worker and Passageway’s program director for the Violence Intervention and Prevention Unit, echoed this sentiment, who attempts to foster healing connections with her clients.

Passageway is a free, voluntary, and confidential program operating in the Greater Boston area, providing empowerment-based advocacy, supportive counseling and case management services to support patients who have experienced or are experiencing dynamics of intimate partner violence.

When you take the step to believe someone’s story you can, “lift them up as an individual who is resilient and surviving and doing everything in their power to take care of themselves and their family because that is what they are doing,” Loftus said. “We must not mistake a survivor’s astounding strength for weakness.”

As a survivor herself, Loftus is devoted to promoting awareness of the severity of domestic violence. She hopes to bring recognition to “how violence is disproportionately impactful on Black and brown bodies in our communities and our culture.”

Loftus said that when confronting domestic violence and gender-based violence, it is important to think of the movement as a racial justice movement as well.

In a 2017 article, the previous CEO of YWCA USA, a nonprofit that works to eliminate racism and empower women, Alejandra Castillo wrote, “Black women experience intimate partner violence at a rate 35 percent higher than that of white women, and about 22 times the rate of women of other races.”

Therefore, to be an active opponent of domestic violence, we must recognize how identity comes into play and the trends in our cultural narratives.

One of the most significant challenges in ending domestic violence is the sheer shortage of resources. Emergency shelter systems are limited, small and always at capacity. Housing in Boston is costly, and people may not have the financial means to move out of an unsafe environment.

Maria Ortiz, the housing advocate assistant of a domestic violence shelter in Roxbury, considered this to be the most pressing issue in current times. She said that there are “simply not enough shelters for people, and the existing shelters are overwhelmed as COVID-19 has exacerbated domestic violence due to spouses quarantining together.”

Seeing a parallel with her childhood, Ortiz recounted the moments when her mother, a domestic violence victim, attempted to seek help in the 1980s when there were not many resources available.

“Very little was recognized about domestic violence at the time,” she said.

Ortiz’s mother had nowhere to go, was not treated for her mental illness and eventually killed her abuser and was sentenced to prison.

Ortiz shared her story in an attempt to emphasize the housing crisis that domestic violence survivors face. She warned that “when [victims] don’t have the means to move, this presents a huge barrier to the possibility of gaining freedom.”

If you or a loved one is in need, please call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at (1) 800-799-7233.

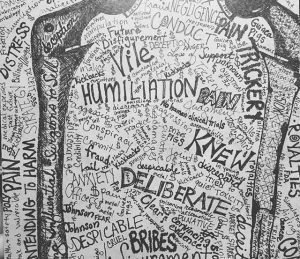

![Worcester, MA — Pearson’s recent piece “Lipstick on a Pig” contends with her self-perception. The title of the painting came to her first, “fixating in [her] head quite a lot,” Pearson said.](https://thescopeboston.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2-300x200.jpg)