By Chris Triunfo and Casey Rochette

In May 2018, a bill that would have required schools to teach sex education failed in Massachusetts’ state legislature.

The Healthy Youth Act would have required schools to follow a curriculum that’s medically accurate, age-appropriate, LGBTQ-inclusive and comprehensive in covering contraception. But after months of inaction, House leadership failed to bring the bill up for a vote.

Massachusetts is one of 26 states where there is no requirement to teach sex education in public schools — and no way of knowing whether the schools that are teaching it are using unbiased, medically accurate information.

“[Students] deserve to learn the rules of engagement as designed by our laws and our norms,” said Gina Scaramella, executive director of the Boston Area Rape Crisis Center, who said that passing legislation that mandates sex education seems like a “no-brainer.”

In an attempt to fill the sex ed vacuum created by a lack of state policy, many college students have been getting involved in teaching. At Northeastern University, the non-profit organization Peer Health Exchange sends college students out to high schools to teach health education in Boston’s Public Schools.

Albert Coincella is a second-year at Northeastern and a new member who is working on passing his training. He grew up in East Boston and expressed excitement about working on something he never had access to.

“A lot of what we teach is something I wish I had learned when I was that age,” he said.

Peer Health Exchange is a national organization that was founded in 2003 to “give teens the knowledge and skills they need to make healthy decisions.” It trains college volunteers in chapters around the country to teach a comprehensive health curriculum in public high schools.

Louise Langheier, 36, co-founded Peer Health Exchange and it has only grown, now teaching nearly 150,000 students across the country.

“When I jumped in, I knew this would be a long-term endeavor, but it’s taken a very long time,” Langheier said. “To me, PHE is no longer a temporary fix. It’s a national community that has built so many relationships and helped so many people. And it seems to be only growing.”

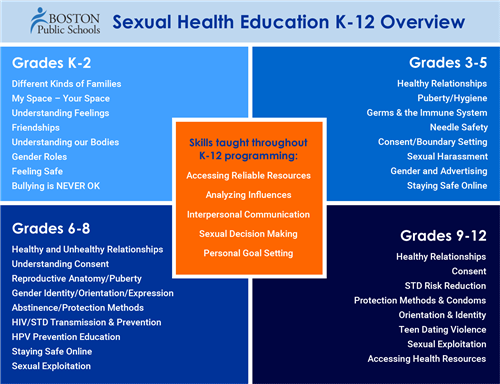

Many Massachusetts public schools do teach sex ed in the classroom. The health education policy for the Boston Public School District mandates that schools provide “comprehensive sexual health education that is LGBTQ inclusive.” In lower grades students are taught about gender roles and understanding their bodies, while upper-level students are taught about puberty, STDs, contraception and healthy relationships.

Through Peer Health Exchange, college students at institutions like Northeastern University, Boston University, Tufts and Harvard volunteer roughly 10 hours every week, learning the material and teaching it to ninth graders at more than 10 different Boston public high schools. The students at Northeastern are paired with the Parkway Academy of Technology and Health, Boston Community Leadership Academy and Urban Science Academy.

But the student volunteers face significant roadblocks, including pushback from conservative institutions.

The Massachusetts Family Institute, a Judeo-Christian advocacy group, is against the installation of any sort of sexual education in the state’s public schools, saying that it should be up to parents to decide whether or not their kids learn about sex.

“We promote parents’ rights regarding the education and welfare of their child. We provide resources outside of any school or public institution,” said Andrew Beckwith, president of the institute.

Beckwith said that passing legislation requiring sex-ed in schools would give too much control to the State Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Most of the bills that have been proposed thus far give the department power to set the rules, ensure compliance with the law and recommend favored curricula.

A desire for parental control over children’s sex education resonates in some households as well, something Peer Health Exchange is aware of. The organization tries to ensure that its curricula is fitting to all residents and students.

Jean McGuire, professor in Northeastern’s department of health sciences, said that it’s crucial that sex-ed advocacy groups be sensitive to families of all beliefs and ideas, and what they might want to teach their kids at home.

“You need to get engagement from the full spectrum of a community,” McGuire, who used to work at the U.S. Department of Public Health, said. “The impact of equity and communication goes a long way.”

Rep. Adrian Madaro (D-East Boston) agrees, but said that he sees families and public education as being two distinct issues.

“Nothing in the bill precludes families from teaching their children their own personal beliefs at home,” said Madaro. “If we’re only exposing young people to one side of that coin, that’s not comprehensive. The more information we can empower young people with the better.”

Madaro said he has witnessed significant momentum on issues of consent and sexual abuse on college campuses, and hopes to capitalize on that momentum in order to pass effective legislation in the future.

Peer Health Exchange has a mission of being anti-racist, anti-nationalist, anti-queerphobic, anti-transphobic, anti-sexist, anti-classist and anti-ableist in its teaching.

This resonates with some local officials, like Rep. Nika Elugardo (D-Roxbury) who said Peer Health Exchange’s method should be considered during the implementation of a statewide curriculum.

“Keeping low-income and socio-economic background in account and understanding that everyone comes from different cultures will help not only establish a curriculum, but keep it going,” she said.

Elugardo hopes to work on a new bill, which she considers to be a better and stronger version of the Healthy Youth Act.

“We’re still in the early days of this session,” Elugardo said. “But as always, it will come up. And I hope to advocate for it.”