Scientists grapple with a possible new consequence of climate change: ‘Zombie’ viruses

“Climate change is changing how infections spread”

Scientists fear too much damage has already been done by the impact of climate change, and there’s no turning back: “zombie” viruses are coming back to life.

The Earth’s climate has been rising in temperatures drastically, with an average temperature of 58.55 degrees Fahrenheit, which is 1.9 degrees higher since 1880 based on NOAA’s temperature data. According to NASA, scientists have not seen a warming rate like this in the past 10,000 years.

What’s more concerning is that there are tiny 48,500-year-old viruses trapped under melting glaciers, and they are releasing into the atmosphere.

“Climate change is changing how infections spread,” said Brian Chow, a physician at Tufts Medical Center and the director of the Infectious Diseases Fellowship Program. “Part of this can be seen in the increase of the range of different vectors of mosquitoes, ticks and other things that can transmit diseases.”

While the viruses are only potentially harmful to humans, they are real threats to members of the global ecosystem, including animals, plants and other living organisms, Chow said.

Chow’s comments are backed by almost a decade of research on the possible crisis.

Researchers posted an updated study on Feb. 2, revealing that because of the sea levels and global temperatures rising continuously, eukaryotic viruses from ancient permafrost in the Arctic are reappearing. According to the results, seven of the reported 13 new “virus isolates” – viruses that were isolated from infected hosts – were found to be new members of the Pandoraviridae family. The Pandoravirus is a genus of a “giant virus” — the second largest virus in physical size of any known viral genus — that infects amoebas, a type of single-celled organism.

It was first discovered in 2013 by Jean-Michel Claverie and a team of French scientists. Claverie is a professor of genomics and bioinformatics at the School of Medicine of Aix-Marseille University in southern France and the director of the Mediterranean Institute of Microbiology.

Since permafrost is thawing every summer, viruses are regularly released into the environment, and it is impossible to estimate how long viruses could remain infectious once exposed to external conditions, Claverie said in an email. However, he said it is unlikely that these viruses would actually infect humans.

“They can decay quickly as soon as they are released because of heat, UV light and oxygen,” said Claverie, who is also head of the Structural and Genomic Information Laboratory, a unit of the French National Research Center.

David Knipe, the Higgins professor of microbiology and molecular genetics at Harvard Medical School, also found in his research that most viruses are not stable in terms of infectiousness once they thaw. However, there is one exception: if the ancient viruses reveal evidence relating to smallpox. Because smallpox has a very stable virus particle, it can freeze and dry, he said.

“It could be dried and weaponized [like] in the blankets given to Native Americans by the invading Europeans,” Knipe said. In 1520, when the Europeans invaded the lands of Native Americans, they brought smallpox with them, killing approximately 90% of the Indigenous people, according to PBS. And in one recorded instance, a European fort commander deliberately gave smallpox-infected blankets to some Native Americans after a dispute. Some experts believe this virus could be found within the permafrost, but it is hard to tell at this time.

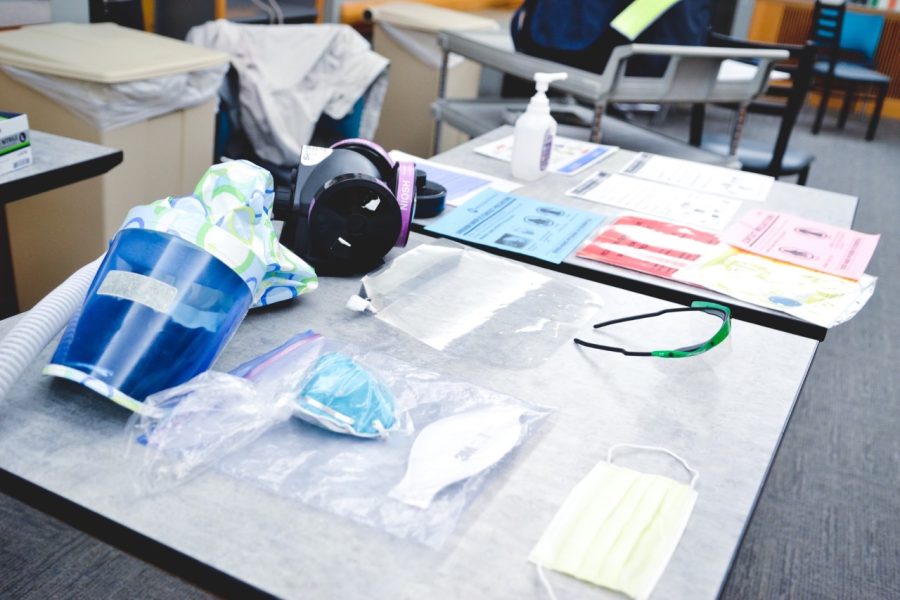

If ancient viruses were to reemerge, experts believe there are already preparatory measures for such a disaster because of the challenges overcome during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I think we’ve learned a lot of things from the pandemic,” Chow said. “We need to have our scientific and manufacturing infrastructure ready to go to combat any new biological threat.”

Another preventative strategy is the development of vaccines.

“Once we’ve determined which viruses might have a threat of reemerging through this pathway, the best way is to either develop or re-implement vaccinations against these viruses,” said Quinn Adams, a Boston University doctoral student in environmental health.

Peter Huybers, a professor of earth and planetary sciences at Harvard University, feels that the viruses are just another consequence of global warming, in addition to other issues like drought.

“It’s another unfortunate expected response to the overall warming patterns that we’re seeing,” he said.

Overall, this rise in temperature is nothing new and will only continue, creating a larger impact over time for infectious diseases.

“Things that were buried in the ice that are reemerging are more of a marker of the unprecedented retreat of ice that has been present with us for a long time,” Huybers said.