Burgeoning ‘intentional communities’ throughout Boston relieve residents’ loneliness in pandemic times

Explore Boston’s intentional communities with our StoryMap. Click on “Start Exploring” to begin. Map by Rachel Gore.

While people all over the country were experiencing the crushing isolation that came with the pandemic last year, residents of Boston’s so-called intentional communities were able to avoid some of it.

“An intentional community is somewhere between a chosen family and a monastery and a sitcom,” laughed 39-year-old Isaac Everett, executive director and a founding member of the Charles River Episcopal Cohousing Endeavor, or Creche. “We’re held together by something much deeper than sharing space. It’s not just roommates. We’re making the intentional choice to invest deeply in each other’s lives, to be vulnerable with each other and to be inconvenienced by each other.”

Intentional communities — groups of individuals who choose to live together or share resources on the basis of shared values — are not new in the United States, but they were historically located in rural areas. Today, they are gaining traction in urban areas. According to a directory maintained by the Foundation for Intentional Community, a nonprofit organization that supports the development of communities worldwide, the Greater Boston area has 11 intentional communities. Since the foundation only lists communities that add themselves to the directory, the number is most likely an underestimate.

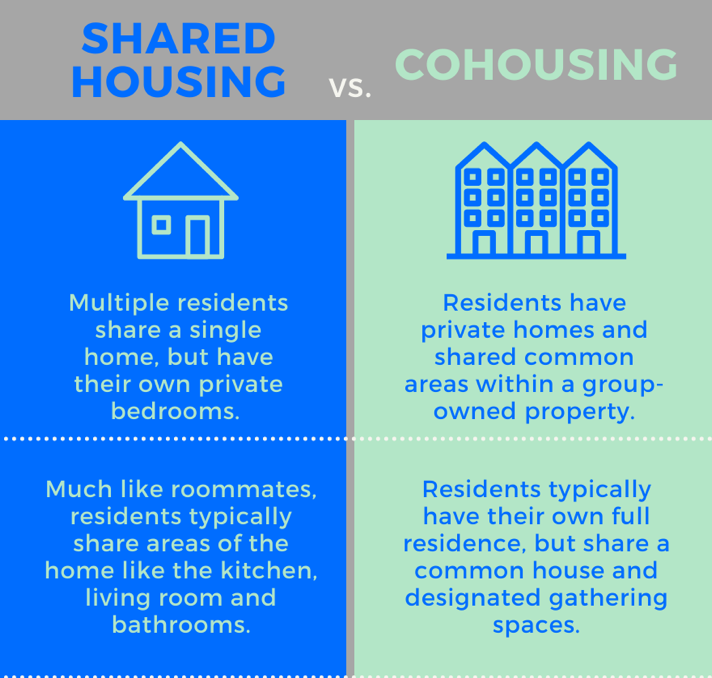

Intentional communities come in several forms, such as shared housing communities, where multiple residents share a single home, cohousing communities, which have private homes centered around shared common spaces, and ecovillages, which are rooted in ecological sustainability. They can be religiously affiliated, but aren’t always.

During the pandemic, residents of intentional communities faced issues around how to maintain a sense of community and live in harmony during a global pandemic. Even so, they overwhelmingly say that such obstacles are worth overcoming.

With any group of individuals living together, interpersonal conflict is inevitable from time to time. In some communities, the added stressor of COVID-19 strained households beyond repair.

Creche is a Boston-based nonprofit that, in partnership with The Episcopal Church, operates three intentional communities in Dorchester, Allston and North Cambridge. Each Creche community has its own Episcopal partner congregation in the Boston area, which so far include St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, Emmanuel Church and The Crossing.

As three Creche homes thrived, the pressure of living under quarantine became too much for a fourth house in Newton to overcome. The residents chose to dissolve the intentional community, which Creche plans to relaunch in the same house this fall.

The Millstone Co-op, a seven-person shared housing community in Dorchester, experienced similar tension among residents.

“Millstone almost disbanded in the summer,” said Kavita Malstead, 25, a resident of the community since January 2020.

When the pandemic struck, Malstead was the only Millstone resident who continued to report to work in-person. Additionally, social distancing guidelines meant residents largely stopped socializing with friends and family who do not live at Millstone. The overwhelming amount of time together and loss of external social outlets caused interpersonal strife that affected the harmony of the entire household.

Millstone residents ultimately made positive changes to the community dynamic and were successful in avoiding disbandment. They spread out people’s bedrooms to give one another some space and bonded over living room workouts, gardening and cooking.

“I think we are an example of a co-op that got over that hump and made some changes, figured it out. It’s definitely an ongoing process,” Malstead added.

The Beacon Hill Friends House, a shared housing community rooted in Quaker values, also experienced conflict between residents. “It’s been a challenging year for most people, and we’ve been experiencing some conflict… [but] I don’t think conflict is always something bad and needs to be avoided. We can see if we can find something stronger on the other side,” said Jeff Edenberg, operations director at Beacon Hill Friends House.

Despite these challenges, intentional communities largely embraced being together throughout COVID-19. During the pandemic, many Creche home residents lost their jobs. But thanks to the support of their intentional community through the redistribution of household expenses and rent relief fundraising, losing a place to live was out of the question.

There are “all kinds of ways that people are really stepping up to make sure that everyone’s needs are met and I’m really, really proud to say that not a single person has had to leave a Creche house because of financial hardship,” said Everett.

Rather than face the devastating loneliness that much of the world was plunged into during COVID-19, Creche residents are navigating a very different obstacle. “How do we keep our community alive when we can’t get away from each other? That’s like the completely opposite problem,” said Everett.

Fortunately, they’re finding ways.

“For the last year, we’ve been able to have movie nights and play board games and order pizza together, and just aren’t experiencing the extreme isolation that a lot of people are,” he explained. When churches cancelled in-person services on Easter Sunday in 2020, Creche home residents took it upon themselves to celebrate the holiday through song, prayer and feasts.

In shared housing communities like those run by Creche, residents generally have their own private bedroom in a furnished home but share other areas of the house like the kitchen and living room. The term shared housing comes from the Foundation for Intentional Community, but some shared housing communities refer to themselves as cohousing, cooperatives or co-ops.

Looking beyond shared housing, another type of intentional community is co-housing. Co-housing communities are designed with private homes, condos or apartments and shared common spaces.

Like shared housing communities, co-housing communities are no strangers to conflict. But they also share stories of times they’ve embraced community, even as a pandemic drove them apart physically.

Infographic by Rachel Gore.

When two residents of Cornerstone Village Cohousing in Cambridge graduated from high school in 2020, in-person graduation ceremonies were not possible. That didn’t stop the community from hosting their own socially distant graduation celebration.

“We spread out on the lawn and we gave them mock diplomas until the ones [from their schools] arrived,” said Carol Agate, a retired judge and Cornerstone resident.

Compared to shared housing residents, cohousing communities experienced greater levels of social distancing among residents themselves. Only some residents were comfortable enough to attend that graduation party and the monthly birthday celebrations that took place outdoors. They suspended community meals, closed common rooms and shifted meetings to Zoom.

And when long summer days faded into a dark winter, outdoor gatherings grinded to a halt. At that point residents largely socialized in smaller pandemic pods. Still, they benefited from casual conversations triggered by inevitable run-ins at the mailboxes or elsewhere in the community.

Now, thanks to the recent wave of warm weather, outdoor gatherings are slowly resuming.

“I think the winter has been more isolated, but now the kids are out playing again and that sort of brings everybody out into the sun,” said Cornerstone resident Judith Adler.

Bay State Commons Cohousing, an in-construction intentional community in Malden with an anticipated move-in date of late 2021 or early 2022, experienced a similar shift away from in-person gatherings. Although the future residents of Bay State Commons have yet to move in, they hosted in-person meetings and events to get to know one another prior to the pandemic. The separation caused by COVID-19 inspired them to work even harder to stay connected.

“The fact that we can’t physically be together really motivated people to figure out what we can do virtually,” said Lydia Thrasher, a future resident of Bay State Commons. “We can get together and do talent shows, we can present travel slides [and] we’ve had a few events where people actually got food delivered to everybody,” she added.

Another future resident, 38-year-old Elizabeth Youngblood, echoed the sentiment that the Bay State Commons community is working hard to stay connected. “It feels like it’s already a community, like it has new people joining [and] it’s fun to bring them in and connect with them and feel welcome,” she said.

But to achieve togetherness as a society doesn’t mean one has to move to an intentional community. “Intentional communities are wonderful experimentation centers for how we can create different societies. There’s a lot that can be learned from the existence of them that can be applied to creating community wherever you live,” said Cynthia Tina, co-director of the Foundation for Intentional Community.