Policymakers, nonprofits leading the solutions for Boston’s affordable housing crisis

In a small basement apartment in Mattapan, Massachusetts, Symone Crawford and her husband raised three daughters while working full time. When Crawford set out to secure the stable home that her family needed and deserved, she found that her struggle to find affordable housing is not uncommon.

Boston has a long and painful history of racist, sexist and classist housing policies — as do most major cities in America. Boston currently has over 40,000 families on the waitlist for affordable housing, mostly made up of families of color similar to Crawford’s. But now, Boston policymakers are tackling this complicated housing crisis by prioritizing the city’s many diverse communities over just its wealthy.

“The Boston affordable housing crisis is affecting everyone,” said Symone Crawford, the director of homeownership education and of STASH at the Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance. “But it is more so impacting those that have been systematically disenfranchised for decades.”

For generations, housing policies in U.S. cities took one step forward and two steps back, as serving profitable families surpassed investing in those in need. Solving the crisis on the national scale consistently came to a halt in past endeavours due to the issue’s sensitive history and its estimated high cost to repair causing political decision-making gridlock, according to information from the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

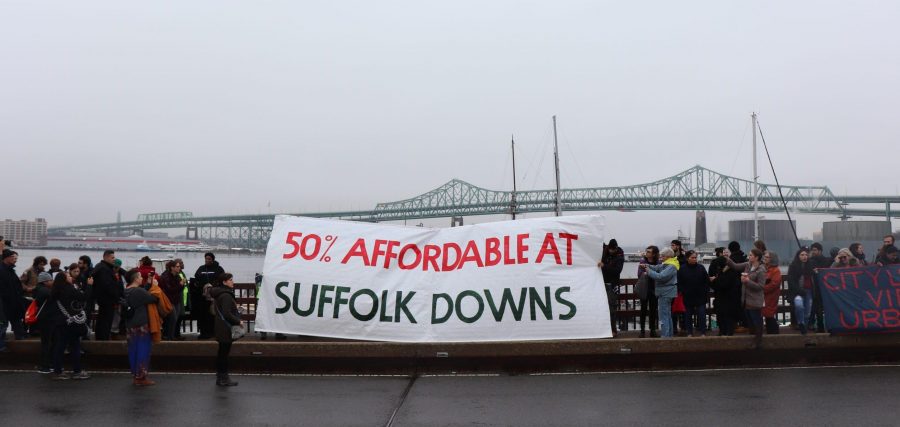

Despite the lack of progress on the national scale to increase access to affordable housing — especially for systematically disenfranchised communities — Boston politicians, nonprofits and residents have joined forces to address the issue through new and comprehensive policies.

What’s Being Done

One of the first major efforts to solve the affordable housing crisis from this new approach was the 2016 Community Preservation Act. The CPA is a community-wide endeavor funded by a 1% property tax-based surcharge on residential and business property tax bills and is used to improve historic preservation, affordable housing, open space and public recreation in Boston neighborhoods.

Leading the effort to enact the CPA at the time was Boston City Councilor Kenzie Bok. She represents District 8 and was elected in 2019 on her progressive housing policies centered on equity. Bok was formerly the senior advisor for policy and planning at the Boston Housing Authority.

“The Community Preservation Act has been a big part of my focus,” she said. “With affordable housing, if people can’t stay in the city, then everything we do to make the city great for people to live in doesn’t benefit them.”

A vital member in the advocacy for the CPA in its “Yes for a Better Boston Coalition” was the Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance. MAHA was founded on the mission to create affordable housing when Massachusetts began its dramatic housing price appreciation in 1985. While that mission remained, after organizers for MAHA reached out to their community, the nonprofit realized it had a vaster issue at hand.

“Disproportionally, it was women of color who responded. It was not just priced out, but it was also what they call ‘redlined out,’” said Thomas Callahan, the executive director of MAHA. “We realized we have another issue too: redlining and the banking industry’s historic discrimination against people of color.”

Earlier this year, MAHA released its “Homeownership Justice Vision: A Plan for ‘Good Trouble.’” This agenda includes bolstering MAHA’s participation in Boston’s ONE Mortgage Program, which addresses the former racial discrimination in the city’s mortgage lending. The Homeownership Justice Vision implements 12 more “race-conscious programs,” including plans to end exclusionary zoning and calls for canceling student debt.

“For far too long, Massachusetts has not done enough to confront an obvious and embarrassing problem,” reads the introduction to the Homeownership Justice Vision. The plan goes on to cite that Massachusetts ranks 46th in the nation for racial homeownership gaps, with the rate of white homeownership double that of people of color.

Bok began serving on the board at MAHA after working with the nonprofit to get the CPA passed. For her latest endeavor, Bok is collaborating with the Department of Neighborhood Development and the Boston Housing Authority to take advantage of recently discovered data from the Faircloth Amendment.

The initial passing of this national amendment placed a limit on the federal affordable housing units allotted to Boston, causing the city to lose much of its affordable housing at the time. Currently, however, the city is not utilizing approximately 2,500 allowed units, Bok said.

Bok plans to utilize these units and their federal subsidies in conjunction with Rental Assistance Demonstration and Inclusionary Development Policy to create sustainable affordable housing suitable for families making 30% or less of the Area Median Income in neighborhoods with historic segregation of people of color.

“We want to be the city that really preserves a place for low-income families,” said Kate Bennett, administrator and CEO of the Boston Housing Authority. “We’re very excited to actually create more units that have that very deep affordability.”

Deeply affordable housing refers to housing that targets a different socioeconomic group than traditional affordable housing, according to Inspirica, Inc., a group of housing advocates in Connecticut: affordable housing is designed for those who earn between 50% and 60% of the Area Median Income, whereas deeply affordable housing targets those who earn only 25% to 35% of the AMI.

The BHA joined Bok on this initiative in early 2020 after the pandemic revealed further impacts that housing disparities have on low- and moderate-income families. The organization found that its residents disproportionately struggle with food insecurity and health issues compared to those in higher income brackets, Bennett said. For the BHA, solving this requires utilizing Boston’s entitled federal assistance to achieve sustainable and deeply affordable housing.

Impact of New Policies

In 2020, the CPA collected millions of dollars to put back into the Boston areas where community members demanded improvements. The 40 recommendations for spending included rental units for the formerly homeless and a reduction in down payments and interest rates for first-time eligible homebuyers in the ONE+ Boston program, which is also supported by MAHA.

As for the city of Boston as a whole, while the housing crisis remains substantial, the number of individuals and families found homeless or in temporary housing decreased from 2020 to 2021, according to the Annual Homelessness Census. Additionally, prior to the pandemic, first-time homebuyers showed an increase throughout Boston and exceeded the national average in 2019, according to the Massachusetts Association of Realtors.

Mother. Daughter. Two homeowners. Generational wealth. #closingtheracialhomeownershipgap #buildingblackwealth #makingblackhistory #mapoli #bospoli #firstgenfriday #firstgenhome pic.twitter.com/3SKnug0TX7

— MAHA (@mahahome) February 12, 2021

Crawford became a first-generation homebuyer with the help of MAHA. She immigrated to the U.S. from Jamaica in the ‘90s and was introduced to MAHA through reference based on her low-income status. Crawford and her husband wanted a stable home for their family — regardless of the high housing prices in Boston.

“These are hurdles that are a big barrier to homeownership that the low- and moderate-income people — BIPOC people — have to navigate in order to become homeowners,” said Crawford. “If you have the desire, the means and you’re working a decent job, you should be able to afford to purchase a home if it is available. But it is just not as easy as that.”

Crawford ended up in a Homeownership University class in 2004, an education program she would later direct after graduating the Homebuyer 101 course and volunteering with MAHA for over 14 years. In 2020, MAHA had 3,198 combined graduates from its record-breaking Homebuyer 101 course and its Homeowner 201 and Condo Owner 202 courses.

In 2019, Crawford also became the director of MAHA’s newest program — the first of its kind in America — STASH. The program directly works to close the racial homeownership and wealth gap in Boston by providing first-generation homebuyers with the opportunity to accrue intergenerational wealth. Last year, 21 families purchased their first-generation home in this pilot program, with 65 on their way.

STASH matches the savings of a first-generation homebuyer who makes less than the AMI. After a candidate graduates MAHA’s Homebuyer 101 class and shows dedication to saving for a home, STASH pledges to assist those who “do not have the bank of Mom and Dad.”

“We need to make sure that we understand the difficulties that certain people endure in order to purchase their home and see what we can do to level the playing field,” she said.

Crawford attributes her three daughters having graduated from various Massachusetts colleges to raising them in a stable home where they did not have to worry about increasing rent prices and unexpected moves. Rather, her daughters focused on how they could reinvest in their communities as the organizations that helped them secure their home have done throughout Boston.

“I am a first generation homebuyer. My mom did not own a home and still doesn’t own her own home,” said Crawford. “My daughter, because of what she noticed and saw throughout my entire home buying process, purchased a home. All of this is because this process taught me how to be a community leader and to advocate for others”