From Boston Children’s Hospital to the Olympic trials: How Dana Giordano got her life back on track after cancer

The 27-year-old Boston resident is one of 30 women in the nation to qualify for the June 18 Olympic Trials in the 1,500 meters and the 5,000 meters. To secure a spot on the US team, she must finish with one of the three fastest times.

The glaring sunlight poured through the windows, warming the living room of her grandparents’ coastal cottage. It was a hot, August afternoon in Martha’s Vineyard, and 14-year-old Dana Giordano wanted nothing more than to swim in the crashing waves and enjoy the fleeting summer sun. But instead, she sunk into the sofa, reached for the television remote and switched on the 2008 Beijing Olympics — her sole form of entertainment amid a painstaking recovery from ovarian cancer.

She kept her eyes glued to the TV screen, watching in awe as Michael Phelps set records in the swimming pool and 16-year-old Shawn Johnson tumbled across the gymnastics floor. Even while confined to her trusty living room chair, nursing the 9-inch vertical scar that stretched across her abdomen, teenage Giordano couldn’t help but envision herself on the illustrious Olympic stage.

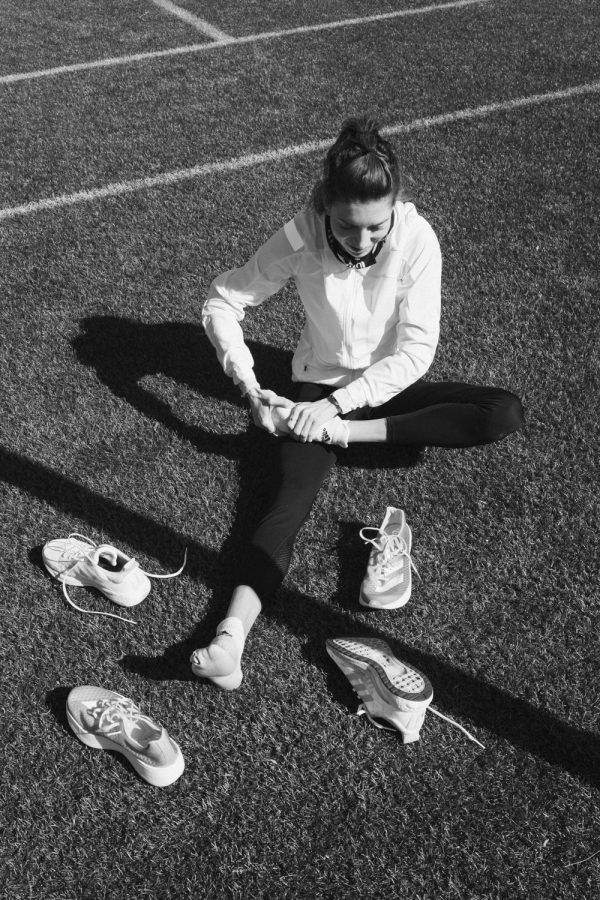

But today, some 13 years later, the 27-year-old Boston resident may very well be competing on that stage. Now fully-recovered and running professionally with the Boston Athletic Association and Adidas, she is one of 30 women in the nation to qualify for the June 18 Olympic Trials in both the 1,500 meters and the 5,000 meters. To secure a spot on the U.S. team, she must finish with one of the three fastest times.

“It would be such a dream come true,” Giordano said, a lifelong dream that she would have achieved in spite of every obstacle in her path. The cancer survivor now bears her scar with pride and seeks to prove that she is just as capable and determined as any other athlete on the track.

“I like her chances,” said Dave Szostak, Giordano’s high school track coach who continues to mentor her and support from the sidelines. “They say that the U.S. Olympic track team is one of the hardest teams in the world to make, but she’s got that will, that determination… I think she’s going to have as good of a chance as anybody.”

Giordano has been a fierce competitor since a young age. She spent her afternoons in the backyard of her childhood home in Bernardsville, New Jersey, playing one-on-one soccer with her father and three siblings, among whom she is the second-oldest. She credits her father with fostering the tenacious spirit that has characterized her career as an athlete.

“I was the soccer goalie at some point when I was super young,” she said. “[My dad] taught me that you’ve got to act like a bear, you’ve got to grab the ball … I was definitely that funny kid who took it all really seriously.”

Athletics became a quintessential element of the Giordano family lifestyle. Weekends were spent skiing in the nearby mountains or driving to the far edges of New Jersey for tournaments in the children’s respective sports.

Giordano initially experimented with both soccer and hockey, but ultimately found her stride as a runner in middle and high school. In a Q&A with Chris Chavez, her close friend and producer of the Citius Mag Podcast Network, she describes her relationship with running as “one of those cheesy love stories where the two heroes meet in kindergarten, and don’t realize they are in love until many years later, when everything clicks and they can’t imagine being with anyone else.”

She said her childhood was “pretty charmed” — until it wasn’t.

In the summer after eighth grade, Giordano noticed what she thought was a bit of extra weight. As she struggled to button her shorts, she said she felt “hilariously excited” — her thin, gangly figure was often a point of insecurity, and, like any other teenage girl, her greatest priority was fitting in at her local high school.

But on a summer getaway in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, that extra weight soon transformed into a sharp pain in her abdomen, which a stranger offered to treat with a Tums tablet. But that wouldn’t do much to help the 5 ½ pound malignant teratoma pushing on the walls of her ovary.

Giordano, now celebrating nearly 12 years cancer-free, laughed about the exchange.

“To think about that now is so funny,” she said. “They were like, ‘Yeah, you can have a Tums, it’ll help!’ I was like, ‘that didn’t help at all. Because it was a giant tumor. But thank you for the thought.’”

But she couldn’t always share her story with such a lighthearted sense of ease. For years, the trauma of her diagnosis, surgery and recovery was difficult to revisit — in fact, she only remembers bits and pieces of the moments leading up to her initial diagnosis.

“I was only 14 years old… I don’t have a lot of these tangible memories and moments from that time,” she said of her days in the hospital. “I just have a sense of panic and fear.”

She can conjure a memory of a gloomy hospital room, trying to stomach the chalky, bitter-tasting solution offered before her abdominal CT scan. She sat in shock as the doctor swung open the door, alerting Giordano and her family that the blood tests suggested a serious condition that required immediate transport to Boston Children’s Hospital.

The massive tumor was on the brink of rupture, an event that would send cancerous cells circulating throughout the entire bloodstream. It was “on its own war path,” Giordano quipped — she even nicknamed the teratoma “ALBY,” short for “alien baby.” The doctors at Boston Children’s Hospital performed emergency surgery to remove her ovary just one day after her diagnosis.

Her mother, Sue Giordano, to whom she is very close, described the ordeal as “terrifying.” Just eight years prior, she had watched her daughter’s grandmother lose her battle to the same disease. Giordano recalled a moment in which her mother gripped her hand and told her, “If I could be in your position, I would. I would do it for you.”

…

The three-month recovery period was particularly challenging for a young athlete so accustomed to constant movement and activity. While she had hoped to run in the annual Falmouth Road Race along the shores of Cape Cod, she could only muster enough strength to watch from the sidelines.

“She was so sick… she walked out with this little leg cane to hold her up,” Giordano’s mother said. “She watched the start, and it must have been really hard to be watching and wishing she were running in it. And to be unhealthy.”

Giordano became all too familiar with the sidelines upon returning to school in Bernardsville. She could barely carry three pounds of weight in her backpack, let alone re-acclimate to the athletic sphere — she often left her textbooks in classrooms overnight to avoid lugging extra weight to and from her home. Her high school soccer coach benched her for much of her freshman season, but this decision ultimately inspired her to pursue running wholeheartedly.

Szostak, who has coached track and field at Bernard’s High School for the past twenty years, immediately saw her potential in the sport.

“I remember telling her mom when she was a freshman like, ‘this kid’s special.’ She’s got a different level of desire that they don’t see very often,” he said. “I mean, I’ve really never seen it before in my whole coaching career.”

Throughout her high school track career, Giordano went on to win the state championship in the mile, become an All-American in the two mile and 3,200-meter races and eventually, catch the attention of recruiters from Dartmouth University. Ironically enough, when the International Olympic committee first announced that Tokyo, Japan would host the 2020 Summer Olympic Games back in 2013, he cracked a joke with Giordano in passing.

“You make it, I’m going to Tokyo,” he told her. The two shared a laugh — even for the track team’s most talented athlete, the prospect felt rather far-fetched. Little did they know they might be packing their bags for Tokyo more than a decade later.

But of course, these accomplishments didn’t come without setbacks. Giordano routinely spent hours in the car, driving to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City for checkups, only to discover a smaller tumor on her remaining ovary just one year after surgery. Doctors were concerned about both a cancer recurrence and her future fertility.

“I was so devastated,” she said, feeling as though one of her greatest fears had materialized. “All I wanted to do was be able to, you know, one year later, be able to put this all behind me.”

However, doctors successfully removed the tumor with no other complications just in time for the famous Falmouth Road Race. Though she was not able to run, she walked and jogged the seven-mile course in benefit of Boston Children’s Hospital.

In the years since, she has run the Falmouth Road Race six times, raising more than $24,000 for cancer treatment and research at the hospital. She raised $10,000 in 2018 alone in celebration of 10 years since her first surgery.

“I’m so grateful that I was able to do that,” she said. “That road race is something that has been this cornerstone of my running experience.”

As a Dartmouth athlete, Giordano won the team title at the conference championships, placed third in the 1,500 meters at the NCAA national championship and was named an All-American three times. But all this time, her Olympic dream lingered in the back of her mind. In the same year she graduated, she competed to qualify for the 2016 Olympic trials — but placed 31st, missing the qualification mark by just one spot.

“Oh my gosh, that could’ve been me,” she thought to herself, as the top 30 women advanced to the trials. She said the loss “got stuck in [her] head” for years, ultimately inspiring her to leave her post-college marketing job with Reebok and pursue running full-time in 2018.

“I was that close… I had to try,” she said. “As an athlete, you only have so much time. So, you’ve got to take advantage of the time that you have.”

Wayne Levy, Director of Athletic Programs at the Boston Athletic Association, saw Giordano practicing at a local indoor track and approached her with his card. Since working closely with Giordano as her team manager, he’s become most impressed with her range as an athlete.

“She’s unique, where she has the leg speed to be competitive in the 1500, but she can also move up to the 5000 and be competitive there as well,” he said. When it comes to the trials, he said, “I like to think that she has a good chance.”

And with the Tokyo trials fast-approaching, she is one step closer to that dream. She appreciated the COVID-19 quarantine period as an opportunity to take a step back, but her training is now back in full swing. To prepare, she runs between 10 and 14 miles each day and routinely visits the weight room, often accompanied by her roommate Heather MacLean, who runs professionally for Team New Balance Boston. They’ve since kept in shape throughout much of the COVID-era with at-home workouts and jogs through the empty Boston streets.

With the 2020 trials put on hold for a year, Giordano began to seek fulfillment in other realms. She continues to give back to Boston Children’s Hospital, the institution that facilitated her cancer treatment and recovery. In addition to the funds she has raised through the Falmouth Road Race, she has volunteered weekly since 2019 in hopes of “helping other children get well and chase their dreams.”

She also headlines her weekly podcast “More than Running” on the Citius Mag Podcast Network, which spotlights female runners who have been sidelined from traditional sports coverage. Her mother said she draws inspiration from NBC sportscaster Mary Carillo’s human interest stories during the Olympics.

“Women only receive about 4% of sports media coverage across all sports, which is wild,” she said. “Then, if you take out like Naomi Osaka, Serena [Williams] and a couple other people, it’s even worse…. So, I just wanted to be a part of the solution to the problem… I’m just hoping to inspire people.”

Some of her favorite guests include Tiffany Chenault, the leader of “Black Girls Run Boston” who is nearing her goal of completing a half marathon in every U.S. state, and Roberta “Bobbi” Gibb, the first woman to cross the finish line in the Boston Marathon back in 1966 wearing a bathing suit top for a sports bra.

Chavez sees her dynamic personality, witty sense of humor and inspiring backstory drawing her a sizable fanbase. With more than 10,000 followers on Instagram and nearly 50,000 followers on TikTok, Giordano has the world in her corner as the trials approach.

“Dana might not be the fastest runner… and she knows that too, because of the talent level, because of how advanced American distance running is right now,” Chavez said. “But she’s got a chance and she’s got so many people online or on the podcast, or who listen to the podcast, who are rooting for her.”

…

Giordano, her friends and her mentors alike know that placing within the top three at the trials is a long shot. However, Levy remains hopeful.

“She doesn’t have the standard for the 1,500. But I know she’s very capable of getting it … she’s definitely dedicated and a hard worker,” he said. “She shows up to practice every day. She’s the first one there and the last one to leave.”

Giordano’s personal bests clock in at 4:08.62 in the 1,500 meters and 15:53.96 in the 5,000 meters. She needs to shave just two seconds off of her current record to meet the 1,500 Olympic qualifying standard of 4:06.00.

“You have athletes that have times that are faster, but when it comes to the time to run the race, they don’t just give the three spots to the three fastest runners,” Levy continued. “Anything can happen.”

But if she has just one thing going for her, it’s her unrelenting positivity in the face of even the toughest hurdles.

“I admire her perseverance and confidence,” MacLean said of her roommate. “She’s never the type of person to go into a race, thinking that she’s not going to do well… she always has a positive mindset.”

As the trials inch closer and closer, Giordano and her supporters are embracing her status as a dark horse and trusting that nothing will break her stride.

“Dana’s had the health issues, she’s had the setbacks,” Szostak said. “But she’s never out of the race.”