The other public health crisis attacking our lungs

For the past year, the world has been worrying about a virus working its way into our bodies and attacking our lungs. Yet, for much longer, certain air pollutants have been lurking in our streets and skies and damaging the systems that let us breathe. These pollutants, long tracked by stations across the U.S., have been tied to a multitude of heart and lung conditions.

One of the five main air pollutants considered in air quality readings, nitrogen dioxide or NO2 is produced by combustion reactions, for instance those that take place in motor vehicles.

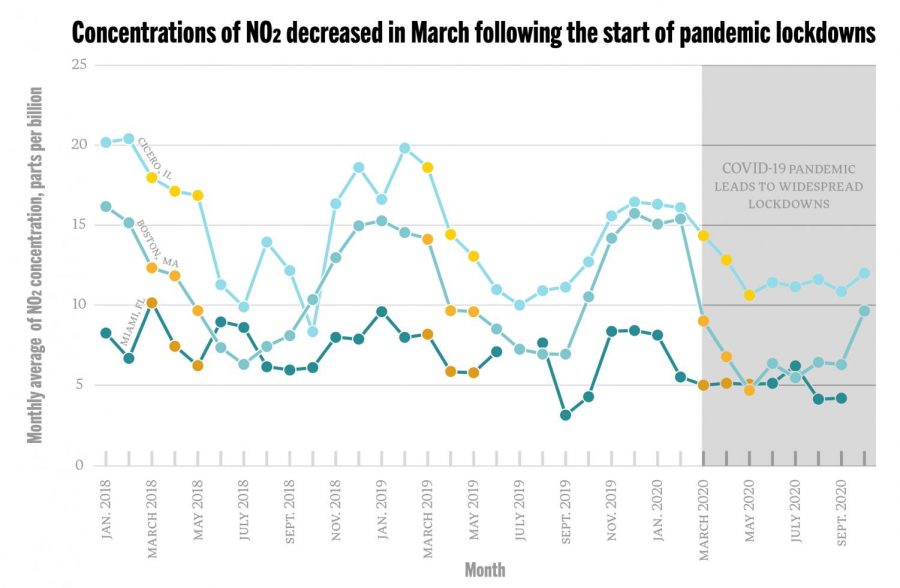

When the COVID-19 pandemic reached the U.S. and started running rampant, many towns, cities and states imposed lockdowns in an effort to slow the spread. As a result, instead of commuting every day, many people stayed home, limiting the pollutants, including NO2, coming from their motor vehicles. Over the first stage of lockdowns from March through May, this change in behavior led to lower levels of NO2 in the air.

In Massachusetts, Gov. Charlie Baker first declared a state of emergency March 10, 2020 and for the next several months severe restrictions were placed on what residents could and could not do.

As the strictest restrictions were put in place and activities known to generate large quantities of NO2 happened less frequently. Pollutants in the air seemed to clear.

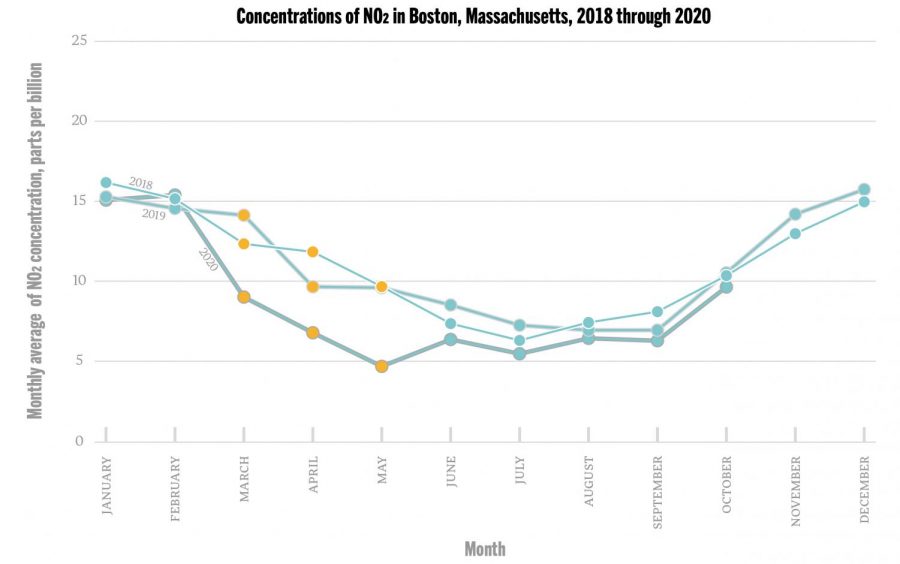

In March 2018, the average concentration of NO2 measured in Boston at a site in Dudley Square was 12.32 parts per billion. In March 2019 it was 14.17 parts per billion. In 2020, as the pandemic ramped up, the average concentration of NO2 measured in Boston dropped into the single digits at just over nine parts per billion.

The trend continued in April and May. In 2018, April’s monthly average was 11.88 parts per billion. By the end of April 2020, now more than a month into the pandemic and lockdown measures, the monthly average of NO2 was nearly half that at 6.778 parts per billion. The averages for May 2018 and 2019 hovered around 9.6 parts per billion. In 2020 it was less than half that.

Much of the knowledge surrounding air pollution and its effects in relation to COVID-19 is still hypothetical. With the official pandemic declaration less than a year old, more research is still needed, but any change in the concentration of pollutants could impact communities where pollution is especially high.

Generally, increased levels of air pollution have been linked to negative health effects, and certain pollutants can be tied to certain recorded consequences. In the case of NO2, the effects are found mainly in areas of the lungs where oxygen enters the blood.

“Air pollution has been shown to negatively affect people’s health, and that’s through several different kinds of health indicators,” said Helen Suh, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Tufts University. “It’s been associated, causally, with increased mortality — especially from cardiopulmonary disease, so cardiovascular diseases and also from respiratory diseases.”

Exposure to NO2 has been associated with increased respiratory symptoms, increased rates of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and generalized decrease in lung function.

While concentration of a single pollutant can and does have effects on people, Suh said a pollutant’s effects can’t be evaluated by itself.

“Air pollution doesn’t just occur by itself; it’s like a soup, right? [NO2] just one of the components of the air pollutant mixtures, so it will co-occur with other pollutants,” Suh said. “Maybe NO2 is more potent when it occurs with another pollutant; or maybe it is additive, like you just have a risk from one pollutant and the risk from NO2 and they do that together; or do they cancel each other out? There’s all sorts of things like that; they call them synergistic effects.”

But air pollution isn’t just an issue in the lab or in data sets; for some, the issue and its effects hit close to home. Sonja Tengblad founded and heads the East Boston chapter of Mothers Out Front, a national organization of mothers who are fighting climate change, for precisely this reason.

“I wanted to start a Mothers Out Front team where I live in East Boston after my son was born and after I became super depressed about climate change — it all really hits home when you have a kid,” Tengblad said. “I started a chapter here and realized pretty quickly we couldn’t address anything related to climate change until we talked about the air quality where we live because it affects everyone but people of color more.”

The issue of air pollution is inextricably intertwined with the concept of environmental racism, the idea that communities of color in the United States face higher levels of hurt from environmental factors. According to the city’s “Boston Neighborhoods in Context”, in the case of East Boston in 2015, 58% of residents were Hispanic and only 32% of residents were white, compared to 19% of residents being hispanic in Boston, and 45% of residents being white.

Tengblad said a lot of the air pollution in East Boston comes from air traffic at Boston Logan International airport and ground transportation to and from the airport.

Mothers Out Front has been working with state Rep. Adrian Madaro to push forward “An act improving air quality in airport environmental justice communities, “ or SD 2323, which Tengblad said calls for HEPA filters to be placed in public schools, an air quality sensor network to measure a fuller pollution profile and a health study.

“It’s one of those things that unless you really know what it smells like it can really go unnoticed and then once you know what it smells like you can’t not notice it,” Tengblad said.

For East Boston residents, the improved air quality in the early days of the pandemic was noticeable. Tengblad and her family went back to Minnesota for six months, but she kept hearing from other members of Mothers Out Front that the air quality improved.

But the changes don’t seem to have been enough, nor have they seemed to last. In October 2018, the average concentration of NO2 was 10.36 parts per billion. In October 2020 it was 9.65 parts per billion. In East Boston, the air still smells black and burns residents’ nostrils.

“I was actually walking around with my son today and it was so bad and I just wanted to cover his mouth somehow,” Tengblad said “A lot of moms talk about that but their kids now recognize it and they feel the need to like run inside or run away from the playground. So definitely once you start noticing it’s hard to escape.”

Note from the authors: The authors of the article chose to compare the concentrations of NO2 specifically in the period of March, April, and May between pre-pandemic years (2018, 2019) and the year of the pandemic (2020) based on the methodologies of a couple scientific studies they looked at.

Generally, after May, lockdowns had been loosened enough that any effects seen would be minimal. The study linked above looked at a six-week period between March 15 and April 25. The authors wanted to look at a similar span of time and compare it to the relative levels in years previous (the values for March 2020 are lower than the values for March 2019 or 2018, etc.).