City officials, community members fight against rising sea level in East Boston

Vulnerable due to its waterfront location, East Boston is at risk of severe flooding in the near future from rapidly rising sea level.

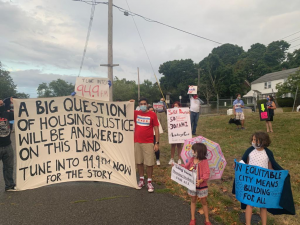

Photo: Kelly Thomas

East Boston

By 2070, nearly half of East Boston could be exposed to flooding during severe storms due to rapidly rising sea level, according to the city of Boston’s climate vulnerability assessment.

Preparing a community for potentially-catastrophic flooding is not a small task, one of the main challenges being who should play the largest role.

Chris Marchi, an East Boston resident who has been an environmental activist for over 20 years, believes the responsibility is everyone’s to share — including “city leaders and departments, state agencies, non-profit organizations, universities, the private sector and residents.”

“The issue is that someone needs to lead a collective effort, and we’re not very good at collaboration,” Marchi wrote in an email.

Home to over 45,000 residents, East Boston is situated on a peninsula — Chelsea Creek curls around the neighborhood’s north end and flows into Boston Harbor, which surrounds its other sides.

Though the entire city will experience the effects of climate change, East Boston is particularly vulnerable because of its waterfront location and the fact that the majority of residents are members of minority groups (low-income, immigrants, people of color or non-native English speakers). Future flooding in East Boston could also impact Boston Logan International Airport, located on the neighborhood’s east side, and interfere with transportation throughout the city and beyond.

Boston’s sea level could rise as many as eight inches by 2030, the city reports, a rate that will only accelerate in the coming years as carbon emissions trap heat in Earth’s atmosphere and cause seawater to expand and ice sheets to melt.

Sea level rise poses a significant threat to coastal communities in two main ways: increased flooding from storm surge — seawater that winds blow onshore during storms — and high tide, or “sunny day” flooding, which occurs when sea level rises significantly during an abnormally high tide. A three-foot sea level rise, predicted to happen by 2070, could cause monthly flooding during these high tide days in East Boston.

The city of Boston released its initial plans to combat the effects of climate change citywide, “Climate Ready Boston,” in 2013 after Hurricane Sandy slammed the Northeast the previous year.

The city released “Coastal Resilience Solutions For East Boston and Charlestown” in 2017, a report that details specific strategies to adapt East Boston for sea level rise, following a Nor’easter that brought significant flooding to the neighborhood earlier that year.

Some of the proposed initiatives for East Boston include constructing deployable floodwalls (one has already been built and tested below the Sumner Street overpass), building coastal berms (raised barriers made of natural materials like soil), elevating areas like the Mary Ellen Welch Greenway (which acts as a main flood channel into the neighborhood) and creating a network of connected waterfront green spaces to buffer storm surge.

These strategies have a “softer, green approach to resilience” that blends into the landscape, a stark difference from “gray” infrastructure like concrete seawalls that cities often build to combat flooding, said Richard McGuinness, deputy director for climate change and environmental planning at the Boston Planning and Development Agency, or BPDA. He said residents heavily preferred this approach in the planning process and said they wanted continued access to East Boston’s waterfront.

Investing to prepare the neighborhood for sea level rise could benefit the city’s long-term economic interests. Proposed short and long-term adaptation measures in East Boston would total a combined cost of $169-200 million and generate a net benefit of $472-591 million.

Another motivating factor for adaptation is East Boston’s role as a transportation hub for the city.

Boston Logan International Airport, located on the east side of the neighborhood, generated over $16 billion in economic activity in 2017. Though the airport is mostly outside the predicted flood area from sea level rise, inundation could eventually impact the MBTA Blue Line and the two major highways that run through East Boston, connecting the airport to the rest of the city.

These three pieces of infrastructure connect East Boston to the rest of the city by tunnels — low points particularly susceptible to flooding. A model from researchers at UMass Boston and the Woods Hole Group predicts the Ted Williams Tunnel, which connects Boston to East Boston, could flood almost every year by 2070.

Economic losses and transportation difficulties are not the only factors planning must take into account.

Because the majority of East Boston’s residents are socially vulnerable, they may have limited economic and social resources to relocate to higher ground or recover from a devastating flood event.

McGuinness said this aspect of the neighborhood is why East Boston was one of the first areas the city has honed in on from the start of their planning process.

“Focusing first on East Boston underscores that concern that we have for this community,” he said.

Critics, however, believe the city may not be centering these vulnerable residents enough in its initiatives.

Madhu Dutta-Koehler, director of the city planning and urban affairs program at Boston University, called the “Climate Ready Boston” plan fantastic and robust, but said the city’s approach is “too formulaic” and focuses too heavily on where Boston will face the greatest economic losses.

“It does not get to the heart of the matter, which is, ‘How are we going to take care of the ones who need it the most?’” she said.

Marchi is also critical of the city’s proposed initiatives. He said city departments tend to cater to the desires of their funding sources, especially large foundations, more than the “inputs, challenges and opportunities they’re exposed to in the neighborhoods.”

“Lost is the chance to build or enhance great city neighborhoods with equitable development that works for everyone,” he said.

Ben Peterson, community design director at the Boston Society for Architecture, said the city’s straightforward planning strategy could stem from the fact that because Boston serves such a large number of constituents, “their approach to this work has to be almost overly pragmatic” to ensure they don’t “promise something that can’t be delivered.”

Sanjay Seth, the city’s climate resilience program manager, said the city is consulting the opinions of residents in their next phase of planning.

Seth said the city is in the process of building a community advisory board for Charlestown and East Boston that they are encouraging both English and Spanish-speaking residents to apply to. He also said the city will compensate board members for their participation and provide translation services for non-English speakers.

“We’re in the process of interviewing folks, pulling them in and really creating a community advisory experience that offers a next level of engagement that the community asked for in our last planning process,” Seth said.

He also said the city hopes to include a diverse range of perspectives in its board. “We want to bring in people who might not have been in the last planning process,” he said.

Another challenge adaptation poses to marginalized people is the possibility of gentrification.

“Specifically thinking about water-resilient infrastructure, there’s a tremendous opportunity to create beautiful places at the same time, and those beautiful places become valuable,” Peterson said. “And, therefore, surrounding territory becomes more valuable.”

Much of the neighborhood’s new development is being constructed with sea level rise in mind.

One example, waterfront Clippership Wharf, is an apartment building that incorporates resilience strategies that include an elevated foundation, deployable flood walls and a living shoreline (a coastal edge with native plants that buffers incoming waves) adjacent to the property.

According to the Clippership Wharf’s website, the lowest rent price for a studio apartment as of Dec. 16 is $1860 a month, an amount unaffordable for many residents of East Boston, where the median household income in the neighborhood is $51,470 and the average rent of nearby affordable housing is $717 a month.

In addition to being unable to afford to live in newer, climate-adapted housing, lower-income residents may have limited resources to prepare their homes for impending flooding.

McGuinness said the city addresses these challenges in the BPDA’s latest planning initiative, “PLAN: East Boston.”

“One of [the plan’s] strongest objectives is to deal with this gentrification and loss of affordable housing and sort of maintain and grow that affordable housing,” he said. “But, it’s also climate resilience, awareness of these risks and what you can do to retrofit your properties.”

He said ensuring that retrofits don’t gentrify a building by causing landlords to raise rents is something that “needs careful attention” in the city’s planning process.

Over the past few years, community members have been fighting against a controversial proposal to place a $66 million Eversource electrical substation near the Chelsea Creek waterfront in East Boston’s Eagle Hill neighborhood — an area many are concerned will flood in the future as sea level rises.

On Dec. 7, 16 of Massachusetts’ elected federal, state and local officials — including U.S. Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey — sent a letter to the Energy Facilities Siting Board to request that they postpone upcoming hearings about the substation and “reopen the determination of need for the project.”

GreenRoots, a Chelsea-based nonprofit that has helped spearhead this fight, has been vocal about the substation’s possible environmental justice impacts.

The organization has been advocating for marginalized people in East Boston who have experienced negative environmental and health impacts from the nearby shipping industry and airport for years.

Noemy Rodriguez, a waterfront initiative organizer for GreenRoots and an East Boston resident, said past meetings and hearings about the substation have not provided any translation to Spanish. About 58% of East Boston’s residents are Hispanic or Latino and 46% have limited English proficiency, according to the BPDA, and as a result, she said, many Spanish-speaking residents who live near the proposed plant’s location are altogether unaware of Eversource’s plans.

“For us, this is an injustice of language,” said Rodriguez, who is a native Spanish speaker herself.

Another local nonprofit, The Harborkeepers, is also seeking to educate the neighborhood about the associated dangers of sea level rise and build coastal resilience.

The organization provides free education about climate change and preparedness strategies in schools, public spaces and other community areas — an initiative that Mary Corso, a board member of The Harborkeepers, said has been integral in raising residents’ awareness.

“A lot of people, really, never know any of this stuff,” she said.

Rodriguez said the flooding that will eventually inundate her own neighborhood is what drives her pursuit of justice for the community’s most vulnerable.

“We are fighting for something that we do not want to see,” she said. “It’s something that we are afraid of.”