How free meal programs in the Boston area are helping to ease food insecurity

Since the pandemic, Massachusetts has seen the greatest percentage increase in food insecurity in the country at 59%

When the clock strikes 4:45 p.m., children in the after-school program at the American Chinese Christian Educational & Social Services, or ACCESS, in Chinatown race to a counter outside of their classroom stacked high with prepackaged food trays.

They run excitedly back to their desks with their meal, which includes fresh fruit and a small carton of milk. Whether they’re nibbling on shredded carrots or struggling to peel their orange, Annie Tran, the director of children and families at ACCESS, knows that the children she cares for “may not acknowledge it, but they do appreciate these meals.”

When Tran was younger and attended after-school programs, she did not have a “display of healthy choices” for snacks, often receiving a palm-sized peanut butter and jelly sandwich or a packaged brownie. Remembering how she would still feel hungry after eating these snacks, she wanted to ensure that the children she serves now did not experience the same, in terms of both quantity and health of the food options.

“Because of these free meal programs being able to emphasize a lot on health, [the children] are not consuming so much cheaper junk food,” Tran said.

The free meal program offered by ACCESS works to combat food insecurity among the children of Chinatown. The organization, which primarily serves low-income families, works to make sure that children are consistently fed healthy food after a long day at school.

More than 100,000 Massachusetts children are food insecure and are facing the threat of hunger daily, according to Feeding America. The ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic aggravate these numbers, but there are now some remedies within the walls of school cafeterias with the help of volunteer and nonprofit organizations. Free meal programs in schools and other food delivery initiatives have played a huge role in the battle to end childhood hunger in the state, offering children healthy meal options and opportunities that they may not receive at home.

Food insecurity rates have been on the rise in the Bay State, especially amid the ongoing pandemic. Feeding America, a nonprofit organization that works to achieve hunger relief in America, reports that one in 11, or 119,300 children, face hunger every day in Massachusetts. The Greater Boston Food Bank, or GBFB, found that in eastern Massachusetts, food insecurity among children rose in 2021 by 117% — becoming one of the highest percentage increases for a food bank’s service area in the United States.

GBFB has also observed general upward trends in food insecurity for households with children. A June 2022 report found that 40% of Massachusetts households with children living in them encountered food insecurity in 2021. This is only a slight decrease from 2020 — where 42% of households with children faced hunger. Structural issues within employment and income flow can exacerbate these numbers.

“We see lots of wage disparities, working folks not earning a living, people working three jobs and not being able to provide for their families,” said Kate Adams, the public policy manager at GBFB. “These are some of the upstream factors that are contributing to food insecurity.”

The same 2022 report found that 32% of adults in Massachusetts experienced food insecurity in 2021 — a 68% increase from 2019. These rates were higher among marginalized communities in the state.

“We are in the midst of a hunger crisis unlike any other in our lifetime,” said Erin McAleer, the CEO of Project Bread, a Boston nonprofit that connects Massachusetts communities to reliable food sources, in an email interview. “Even before the COVID-19 crisis hit, far too many Massachusetts residents were facing food insecurity.”

Currently, there is a light at the end of a very long tunnel with this issue. Six states, including Massachusetts, have guaranteed free meals for all students attending a school participating in the National School Lunch Program, or NSLP, for the 2022-23 school year. Created in 1946, the NSLP is a federally assisted meal program that operates in 95,000 public and nonprofit private schools and, most recently, has offered free or reduced nutritionally balanced lunches to over 26 million American school children daily.

“Universal free school meals in Massachusetts have been an enormous success over the past two school years,” McAleer said in the email. “In March 2022, lunch participation was 42.3% higher for school lunch over pre-pandemic (March 2019) participation rates in schools not previously able to provide universal school meals. Statewide this represented an additional 53,744 more students eating lunch daily when free from the barriers of the old rules of the National School Lunch Program.”

As food insecurity becomes a more discussed issue, solutions become more urgent. With children attending school for a majority of the calendar year, free or reduced school lunches have become an emerging remedy to hunger throughout the region.

The Healthy, Hunger Free Kids Act of 2010, a successful law that focused on enacting policies to end childhood hunger and promoting the overall physical health of children through nutritious school meal programs, expired in September 2015, but the programs are still in operation. In July 2022, a reauthorization bill called The Healthy Meals, Healthy Kids Act proposed a strengthening and expansion of the 2010 act in terms of meal programs during the summer and at after-school care centers.

The Healthy, Hunger Free Kids Act contains the Community Eligibility Provision, which “allows the nation’s highest poverty schools and districts to serve breakfast and lunch at no cost to all enrolled students without collecting household applications.” In Somerville, Massachusetts, there are seven schools that are eligible for this provision, said Karyn Novakowski, the nutrition and sustainability coordinator for Somerville Public Schools.

The provision allows families to bypass the application process for free or reduced school lunches, a detail that may be important to many families in the district.

“There are some families who aren’t comfortable applying for free or reduced lunch or don’t know how to do it,” Novakowski said. “Even with all the support that we give to people who are non-native English speakers, there can still be a huge barrier. So I think it impacts a lot more kids than we realize to have free lunch for everyone.”

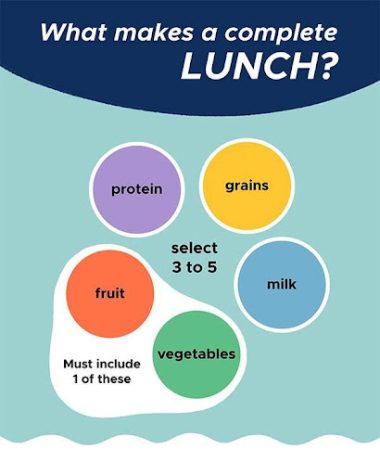

The Somerville school district has a standard set for healthy eating in cafeterias. Students are required to take a minimum number of components from certain food groups for each meal, ensuring that their diet is balanced and nutritious.

“A lot of the time, breakfast, lunch and after-school snacks served at school are the only meals that some kids are getting in a day,” Novakowski said. “So it’s really important to us that we offer a variety of choices throughout the week.”

This free meal program in Somerville provides students with the foundation to lead healthy lives in the future.

“I think one of the benefits is that we are able to provide not just a variety of nutrients, but a variety of different flavors that come from a variety of cultures,” Novakowski said. “When they go out into the world and they have to make their own choices about food beyond just what their family is able to provide, they will hopefully be more open to eating a variety of foods.”

Keira Kolostyak, a sophomore studying architecture at the Wentworth Institute of Technology, grew up with free breakfast and lunch at her middle and high schools in Massachusetts. She and many of her peers ate school lunches almost every day, something she believes was convenient to both child and parent alike.

“It can be a hassle to have your parents pack you a lunch. Of course, when you’re a kid, you don’t make your own lunch,” she said, later adding, “Free meals allow students to not feel pressured to have a packed lunch and their parents don’t have an added pressure of making it.”

Kolostyak also views free school meals as an equalizer among children, especially when the cafeteria can contain students from different income backgrounds.

“Say a kid has a lunch packed for them with a really nice meal; another kid may not have that same privilege,” she said. “I think that free meals create a way to keep the kids from feeling pressured to have a certain type of meal, because with them, all the kids just equally have one healthy meal.”

Food insecurity is an ever-present issue in local communities. With the help of committed volunteers and advocates working for policy changes, there is hope that affected parents and citizens can stop wondering when their next healthy meal may come around.

“Do I put food on the table for my kids or do I pay the electric bill?” said GBFB’s Kate Adams. “These are the kinds of questions that nobody should have to face.”