Urban educators struggle to support students post-pandemic

Public schools in Lynn and Boston are working to find a balance between supporting students’ emotional needs and getting them back on track academically

A teacher in the urban community of Lynn for more than 20 years, Nancy Mades-Byrd has seen dramatic changes in her students following virtual learning, much of which she attributes to the trauma of the pandemic.

“For that first year back, I saw behaviors in eighth graders that I’ve never seen before,” she said. “They were bringing comfort toys to school and playing with them and using them. …For me as an educator, and I’m a mother and a veteran teacher, it made me feel like they were really scared because they were regressing to more childlike behaviors. They were in freeze mode.”

More students than ever are going through mental health crises, according to a report published by the American Psychological Association. And for those who aren’t experiencing overt crises, they have still missed out on important social development due to online learning and pandemic stress. Mades-Byrd said it’s impossible to recreate the “intangibles that make a classroom work” online, inhibiting students’ ability to form meaningful relationships.

Even those who don’t work in the classroom daily have noticed these changes in students.

“I can say anecdotally that what I have experienced is definitely a social stagnation,” said Tiffany Magnolia, a member of the Lynn School Committee and the leader of her daughter’s Girl Scout troop. “It’s like everyone is a year behind where they should be. It’s almost like time stood still for them. It passed, but they didn’t continue to evolve socially and emotionally.”

Once students were able to return to classes in person, some struggled to readjust, with Mades-Byrd seeing how her students were less talkative and social than in years past. Shira Doron, an infectious disease expert at Tufts University, said that the mask requirements hindered some students’ social development even after virtual learning was over, especially for students who are hard of hearing or have speech impairments.

“There’s stories about children who have been essentially living for two years in a complete state of isolation because they had no idea what was going on around them,” Doron said. “Stories about children who had speech impairments and that mask just made it that much harder for their teachers and their peers to understand them, so they would really just stop talking altogether. But also children on the autism spectrum who had sensory issues that made mask-wearing really, really uncomfortable.”

Recovering from this social stagnation isn’t the only thing on educators’ minds, with standardized test scores declining around the country. Some educators are focused on pushing harder to make up for lost academic time, as some students say they didn’t learn as much or as effectively in a virtual environment.

“I definitely learn more in school because you get distracted when you’re on Zoom,” said Olivia Erwin, an eighth grader from Attleboro, when asked about the difference between virtual and in-person learning. “I prefer being in school, but I don’t think the Zoom was very challenging.”

Although Massachusetts still leads the country’s rankings with the most students proficient in both reading and math on the National Assessment of Education Progress, or NAEP, there was a significant decline from the 2019 scores to the 2022 scores. The Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment Exams, or MCAS, showed that only around 40% of students are meeting or exceeding expectations in math and reading, compared with closer to 50% in 2019.

Educators are working to find a balance between supporting students’ emotional needs while still getting them back on track academically.

“It’s really hard because there is tremendous pressure on us to bring these kids back up to where they were academically,” Mades-Byrd said. “But at the same time they’re saying, ‘We recognize you have traumatized children in your classes, and you are going to for the next 10 years. So we’re going to give you training, and we’re going to allow time for social and emotional learning to help these kids who we know have trauma. But at the same time, you better get those scores up.’”

Some parents have picked up on the struggles that individual teachers are dealing with, and not all parents feel that they are supported by administrators either.

“I think there’s a massive disconnect between BPS [Boston Public Schools], the administration, versus, at least our experience, with BPS teachers,” said Johannah Haney, the mother of a sixth-grader in Jamaica Plain. “And the difference is that the teachers were extraordinarily thoughtful and nuanced about how they approached the return to school. The communication from teachers, at least the teacher that she had in fourth grade when they went back, was superb. Versus the administration, who I feel like did not truly have the best interest of students at heart.”

Megan Costello, a senior adviser in the BPS Office of the Superintendent, said students were on a hybrid schedule for the later part of the 2020-2021 school year, which was an adjustment for everyone involved.

“That was really challenging for our educators, but they were phenomenal through it to really try to make sure students had as much support as possible,” she said. “We definitely did see how even being in person a few days a week really helped kids reconnect and learn material, obviously every student learns differently.”

In Lynn, school officials say they are developing curricula that are sensitive to the trauma of COVID-19 experiences. Magnolia, who is the chair of the curriculum subcommittee of the Lynn School Committee, said she is working to make sure that social and emotional development will not suffer as teachers push students to catch up academically.

“What’s clear now is that if all we focus in on is academics, then we’re going to compound the stress of the pandemic,” she said. “Students can’t perform well when they don’t know where their next meal is coming from, or they’re facing homelessness, or English is just not frequent enough for them. Our last school committee meeting, in which we had the MCAS report, one of the things that I specifically said is that if we don’t strike a balance between accelerating our academics and the social and emotional, we’re actually going to suffer more with the academics by pushing them too much.”

Part of this effort, Magnolia said, is to incorporate social and emotional learning into the pre-existing curriculum by including reflection time where students can share their personal experiences and connect with each other. For some schools in Boston, like the one that Sharin Horvitz-Chung’s ninth-grade son attends, this included adding a separate wellness block in the weekly schedule — but this varied in success.

“It ended up being voted down by the teachers at the end of the school year because the schedule made it hard for them,” Horvitz-Chung said. “The families liked it, but the teachers didn’t.”

Lynn and Boston Public Schools are both facing additional pressures as large urban school districts with many lower-income families to support. Lynn’s median household income and per capita income both fall below the national average, with 14.9% of its residents considered “in poverty” as compared to 11.6% of the whole country. A whopping 17.6% of Boston residents are considered in poverty.

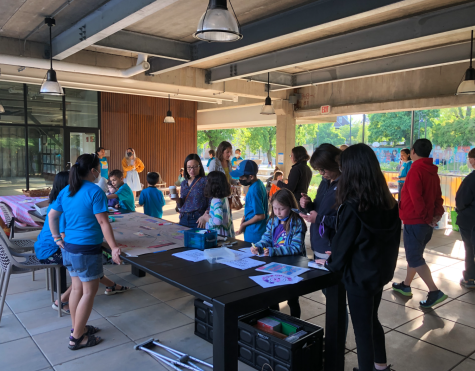

Both districts are benefitting from the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, or ESSER, as part of Congress’ Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. Some of the funding is being used to establish new programs to help students with their homework or encourage learning outside the classroom.

“Right now in our parent council discussions, a big thing is: What are we going to spend our ESSER funds on?” Haney said. “A lot of that is after-school activities. Our school is starting a math club, a writing club, and we didn’t have anything after school before. This is a big change.”

Haney’s school isn’t alone in introducing or improving their selection of activities outside of school. Horvitz-Chung said her son’s school created an after-school wellness program based on the block that they had eliminated from the school day, and Magnolia said the Lynn school district introduced an enhanced summer school open to all students last year.

On a more systemic level, Costello said that BPS has used some of its federal funding to invest in temporary staffing to help support the mental health and academics of the students. This includes additional tutoring, as well as ensuring that each school has at least one nurse, social worker and family liaison to offer emotional support to students.

Given the problems that students are dealing with coming out of the pandemic, “making sure our staff is very mindful of that is priority number one,” she said. “But then also making sure that there are the resources at the schools to refer students who might need those supports. If our students don’t feel safe, if our students don’t feel like they have a person and a trusted adult they can go to, they’re not going to learn.”

The Lynn school district’s most recent Student Opportunity Act Plan shows a similar commitment, with the goal of hiring 35 additional social workers by 2023. This would bring the social worker to student ratio down from 1:643 in 2021 to 1:250, meeting the National Association of Social Workers’ standards.

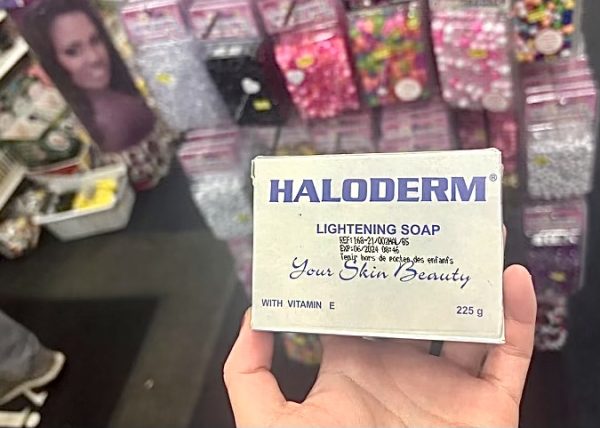

Magnolia said this kind of change can support the students — especially those who are low-income, had parents on the front line or who experience systemic racism — who experienced an outsized impact from the pandemic. For minority-majority districts, like Lynn and Boston with their 82.7% and 86% non-white student population, respectively, ESSER funds are making a big difference.

Tori Cowger, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard and one of the authors of a recent paper that looked at the effects of masking in Boston Public Schools, explained that a long history of systemic racism means that low-income Black and Latinx communities were especially impacted.

“Any sort of discussion about health and educational impacts for kids in schools really needs to start with a conversation about health equity,” Cowger said. “That conversation, I think, starts with the premise that school conditions were not equal even prior to the pandemic.”

With all these additional programs and staff, educators have hope that students will continue on the path of recovery, eventually returning to — or exceeding — pre-pandemic expectations for both mental health and academics.

Mades-Byrd is among these educators. She thinks her students are bouncing back, a refreshing sight after “basically speaking into the void” during cameras-optional remote learning and then teaching in quiet classrooms following students’ return.

“When we first came back they wouldn’t even talk to each other. Now they have fun, they play around with each other,” Mades-Byrd said. “They want joy, they want fun, they want to be out in the world in a way they were not asking to be out in the world before. They’re asking for field trips all the time. They weren’t out in the world for a long time, and they want the world.”