Coronavirus could sideline important period poverty bill

Activists concerned that legislative agenda dominated by COVID-19 will delay menstrual equity, yet again.

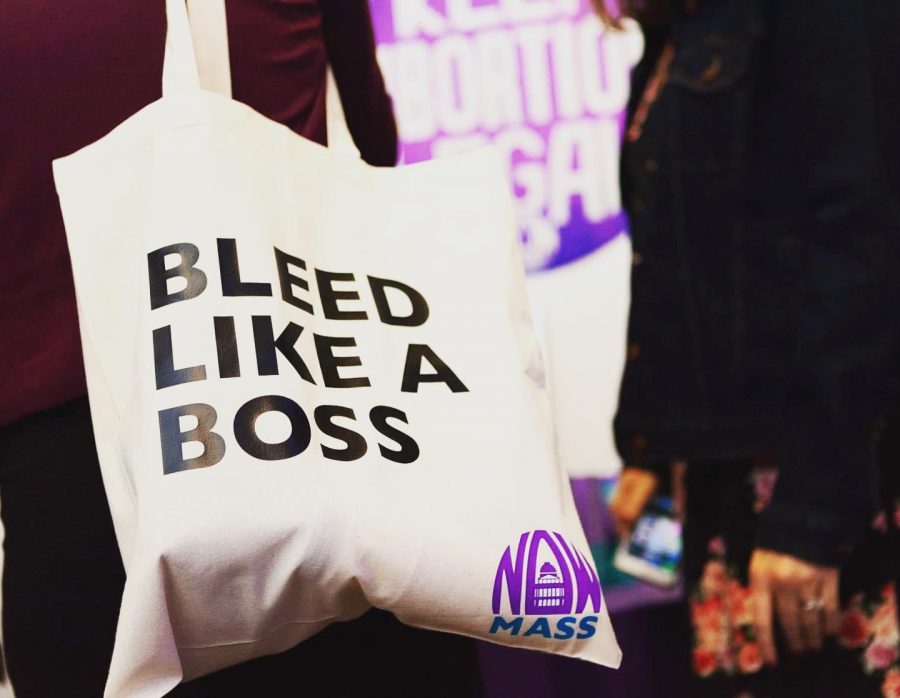

Photo: Mass NOW’s Facebook page

Mass NOW members hand out these bags to raise awareness about period poverty.

Menstrual equity is not an issue often debated up on Beacon Hill.

But activists across Massachusetts are leading a movement against period poverty — lack of access to menstrual hygiene products — and fighting to open up political dialogue on what is still considered a taboo subject.

“Menstrual equity is not a new issue,” said Sasha Goodfriend, president of the Massachusetts chapter of the National Organization for Women, or Mass NOW. “We’ve been menstruating for our entire existence as a species, and yet it is new to be talking about menstrual equity as a public policy issue.”

Goodfriend and other advocates have been working with state representatives to pass the I AM bill, which aims to increase access to free sanitary towels and tampons in public schools, homeless shelters and prisons.

Now, in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, they worry that the bill will be sidelined during the upcoming legislative session.

“Legislature on the state level is one thousand percent consumed with addressing the virus,” Goodfriend said. “We are going to continue our lobbying in the digital ways that we can, but the feedback that I’ve heard from legislators is that realistically, right now, we just need to address this crisis before we can address anything else.”

The bill was co-written by Mass NOW and lead sponsors Sen. Patricia Jehlen and Reps. Jay Livingstone and Christine Barber. It was reported favorably by the Joint Committee on Public Health in December, and is now sitting in the Joint Committee on Health Care Financing. If reported favorably there, it will move to the floor for a vote this session.

Financial concerns about how the state will afford to provide free menstruation products have been largely alleviated, thanks to a cost analysis conducted by Kimberly Blair, a recent graduate of the Boston University School of Public Health and co-founder of the school’s Period Project.

U.S. consumers spend more than $2 billion a year on menstrual hygiene products. Blair’s analysis, which she presented to the Joint Committee on Public Health, concluded that passing the bill would cost the state about $3,000 per school, $9,600 per shelter, and $47,300 for all state prisons during the first year of implementation. The bill would impact more than 230,000 menstruating students across 849 schools, as well as about 10,000 homeless people and 500 prison inmates.

“There’s not actual pushback on the idea, and our legislators have also been surprisingly supportive,” said Diya Khullar, a 21-year-old Northeastern student and menstrual equity activist. “I think it’s one of those issues that most people understand, they just don’t think about it until someone brings it up.”

Delayed conversation and legislative action is not surprising, Goodfriend said, given that lawmakers in this country have predominantly been male non-menstruators, and menstruation remains a heavily stigmatized topic.

As a student with endometriosis, which can cause excessive menstrual bleeding, Blair has experienced this stigma in schools first-hand.

“I got into a lot of trouble over my period, which would have been very easily resolved if these products were just accessible to me in the school bathroom,” Blair said. “All the shame and stigma that came with talking to teachers that didn’t understand endometriosis and didn’t understand what I was going through could have been avoided.”

Mass NOW organized a protest against menstrual inequality outside Boston’s City Hall last October.

But, just as the movement seemed to be gaining traction up at the state house, a new challenge has arisen. With issues related to the coronavirus pandemic consuming the legislative agenda, bills like this one will likely be delayed.

“The challenge is really going to be keeping the pressure on the higher legislative body to pass the bill, especially now with everything being stopped because of coronavirus,” Goodfriend said. “It’s a matter of keeping this an urgent matter and a priority.”

Khullar hopes that the bill will remain a priority despite the pandemic, noting that its provisions are more important now than ever before, as the global pandemic exacerbates socioeconomic inequality and makes it harder to access menstrual products. People who have lost their jobs or have seen a dramatic cut in their pay as a result of the virus, will find it increasingly difficult to afford these items, while stockpiling by shoppers is making it harder to find them in stores.

“With the virus, we are thinking about necessities like toilet paper and paper towels, healthcare, public health and housing now more than ever,” Goodfriend said. “The fact of the matter is that menstrual products are also a necessity, and so we need to treat them as such.”

Proponents are optimistic that the bill will pass eventually if not this session, and they hope that the menstrual equity movement will continue to move toward consideration as an essential social and political conversation.

“I think once people realize that this issue is actually pervasive in a lot of other areas of life, it’s just going to keep gaining momentum,” Khullar said.