After another long night of studying, Jace Shneyderman finally made it back to their dorm building on Boston University’s campus. Like most nights, Shneyderman wasn’t wearing a leg brace despite experiencing intense pain.

As the second-year biology major entered the elevator and pressed the button for the second floor, two girls joined Shneyderman. One immediately turned to the other and audibly voiced her disdain for people who take the elevator up only one or two floors, except when the person has a visible physical impediment, if they use a brace or crutches for instance.

Shneyderman was too exhausted to say anything, but the dirty looks and comments were nothing new. Although Shneyderman looks capable of taking the stairs, the 18-year-old lives with Type 1 diabetes and peripheral neuropathy — a condition that causes nerve damage in the hands and feet. Shneyderman often takes the elevator to the second floor to conserve walking strength. At a school of over 30,000 students, Shneyderman finds it difficult to feel understood, and since no one can see their discomfort, Shneyderman is frequently judged for being lazy.

“If somebody can walk, don’t assume they can do that all the time,” said Shneyderman. “You don’t know what people have to work through to be where they are.”

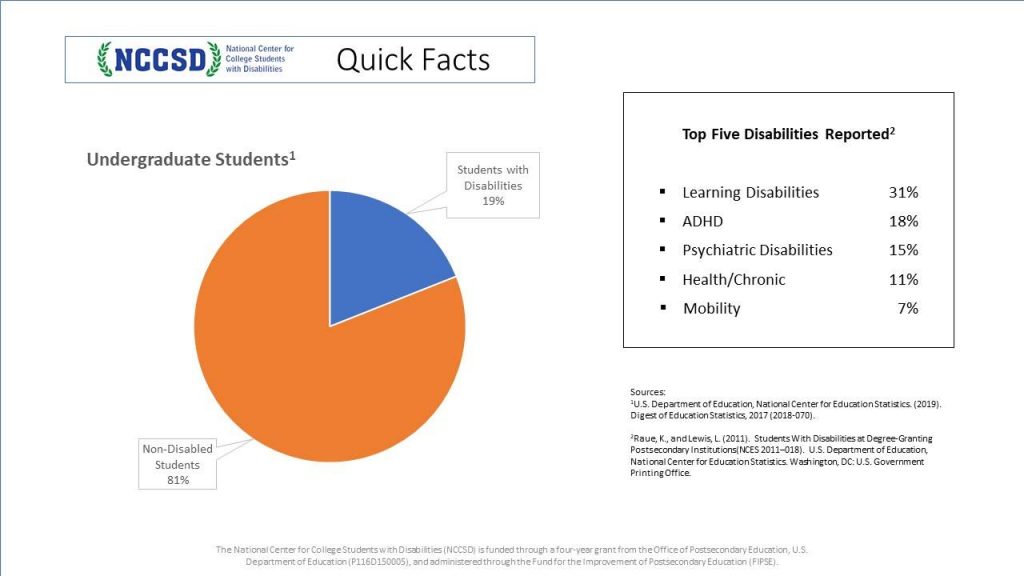

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), 19.4% of undergraduate college students reported having a disability, including non-visible disabilities, in the 2015-2016 school year, the latest cohort for which data is available. A non-visible disability is any physical, mental or emotional impairment that is not immediately apparent.

When students with non-visible disabilities begin college, they enter a new chapter of self-reliance. They must find inclusion on their own, while facing “ableism,” or discrimination against people with disabilities. In high school, students with disabilities are spoken for by their parents. But when they enter college, they must advocate for themselves and they can feel lonely. Experts say this won’t change until the reality of disabilities becomes part of the conversation on college campuses.

“Disability services isn’t the only place that provides information about disability. You should be learning about disability in your classes. You should be talking about it and reading about it in critical ways. It is very rare for students to be doing that,” said Wendy Harbour, the director of the National Center for College Students with Disabilities.

Based out of North Carolina, the NCCSD is the only federally funded center in the U.S. for college and graduate students with any disability, visible or not.

Harbour said it is hard to feel included when a student always feels different and faces rejection on campus. These students often blame themselves, rather than ableism, for feeling alienated, leading them into a negative cycle of pulling away and further isolation.

There has been progress with the implementation of programs for students with non-visible disabilities, but stigma on campus remains.

Think College, a national organization devoted to improving higher education for people with non-visible intellectual disabilities, reports that there are currently 281 programs active in colleges nationwide for students with intellectual disabilities. But, these programs are only operating in 5% of colleges in the U.S., said Cathryn Weir, program director for Think College. She said this number is rising, but the degree to which these students are included in their campus community varies greatly. Even where programs are provided, Weir said there is a lack of access to the social inclusion other college students have.

“Systems have been set up without persons with disabilities in mind. They get excluded or become an afterthought. To a certain degree, it is a university’s job to make sure the culture is accommodating and inclusive,” said David Scanlon, associate professor in teacher education and special education at Boston College.

Stigma faced by students

Toby Kaufman, a second-year biology major at Northeastern University, was diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder a year and a half ago. The 19-year-old doesn’t believe this label changed him, but he faces many students who misunderstand him and disrespect him.

Kaufman said he frequently breaks social norms by saying the wrong thing without thinking beforehand. Other students assume he is being intentionally rude because he doesn’t present as somebody who is disabled.

“Since nobody knows I struggle with some things, they misjudge me as a person,” he said.

When he’s in public, Kaufman said he’s always trying to mask his disability. He tries to present as someone who is neurotypical by thinking about what he is going to say before he says it. But at home he feels comfortable, he lets his guard down and makes more mistakes.

“I can drive people away because I can’t explain myself well enough before I get comfortable around them,” said Kaufman.

College students with non-visible disabilities often have trouble fitting in social groups around campus. “One challenge is that they spend a lot of time dealing with the fact that other people do not automatically see the disability. Many have stories about others thinking they are lazy, stupid, antisocial [and] rude,” said Harbour.

This is common for Lauren Mensch, a second-year communications major at Northeastern, who has to remind friends and colleagues that she needs to take frequent breaks because she gets tired quickly. She wishes she didn’t have to bring it up all the time, but if she doesn’t, she said people won’t adapt for her.

“People don’t accommodate for it the way they would if they could see it,” said the 19-year-old who was diagnosed with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, or POTS, three years ago. POTS is a condition that affects blood flow and is considered a form of dysautonomia, a disorder of the nervous system.

Mensch believes things would change if people were more aware of non-visible disabilities. “You get a lot of organizations doing things like breast cancer awareness. We are past the point of raising awareness for that. This is the peak time for raising awareness for dysautonomia,” said Mensch.

Kassandra Sherwood, a third-year finance major at Northeastern, said some of her close friends struggle believing her pain.

Last year, the 20-year-old was diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos Hypermobility, a connective tissue disorder, leaving her with extreme joint pain and fatigue. She has friends that assume she is mad at them after she rejects their request to hang out. But in reality, she says no because she is fatigued, hurting and needs to sleep.

“People don’t understand. I don’t look like anything is wrong with me, but I am tired,” said Sherwood.

To find inclusion and feel like they belong on campus, some students, like Sherwood, find it easier to just keep their disabilities hidden from others. “People with physical disabilities are automatically judged and treated a certain way because people see their disability before seeing they are human,” said Scanlon.

Samuelguy Strom, a second-year film and television major at Boston University, keeps his disability to himself.

“There is a sense of accomplishment if you are able to sort of put it away. At that point, you are not disabled if you are able to get away without telling anyone,” said the 20-year-old who was diagnosed with Asperger Syndrome, now known as Autism Spectrum Disorder, as a child. “There is a sort of paranoia that they have figured it out. I try not to dwell on that.”

Support grows for college students with non-visible disabilities

As students with visible and non-visible disabilities continue to enroll in college, they are looking for a wider range of resources besides alternative forms of textbooks or the other traditional services provided by campus disability offices. They are seeking complex social. emotional and personal support.

“Most disability offices are run by white women. Students are going to start to push that and ask why they aren’t seeing anyone who looks like them,” said Harbour. Students with non-visible disabilities want guidance from people they can relate to.

Technology will also play a role in helping students with disabilities gain independence. Apps may help them perform academic tasks, such as note-taking. Social media can help students with non-visible disabilities feel more connected to groups and minimize isolation on campus, said Johnson.

“The most powerful voice is the students themselves,” said Weir, who believes students have the greatest potential to change the current system. High school and college educators need to help students learn about their disability and practice running meetings, and gaining the skills that will benefit students with disabilities once they graduate, she added.

Educators are becoming better equipped to assist students with non-visible disabilities as understanding about their conditions and awareness of inclusivity grows. But there is still room for improvement.

Mensch said her learning suffered when faculty failed to understand her condition. A professor once gave a different version of Mensch’s exam to the disability resource center and failed to explain how she should complete it. Mensch had to go out of her way in order to get the same level of instruction that her classmates had received. “I can only do so many things in a day. I am much more limited than other people. Going to office hours [uses] more energy than I have to exert,” Mensch said.

Community matters

In terms of support, colleges have more to do to help students with disabilities feel like they belong. To build a truly welcoming and inclusive environment, Scanlon said colleges need to let the public know, whether it is through brochures, on campus or on their website, that there is academic support as well as a community available on campus.

“That is a big part of it. Making a commitment and making that public so people can be aware of it,” said Scanlon.

Students with non-visible disabilities said colleges are now succeeding in providing resources, accommodations and even job opportunities, but there is still a lack of community on campus. After coming from high school where they had a support network of friends and family, Shneyderman said it’s important to feel a sense of community.

“Disabilities are really isolating. It’s harder to feel like people understand, especially going into a new situation where you don’t have close friends like high school,” Shneyderman said. “It’s about helping each other find support on campus and having a place of people who get you.”