By Catherine McGloin

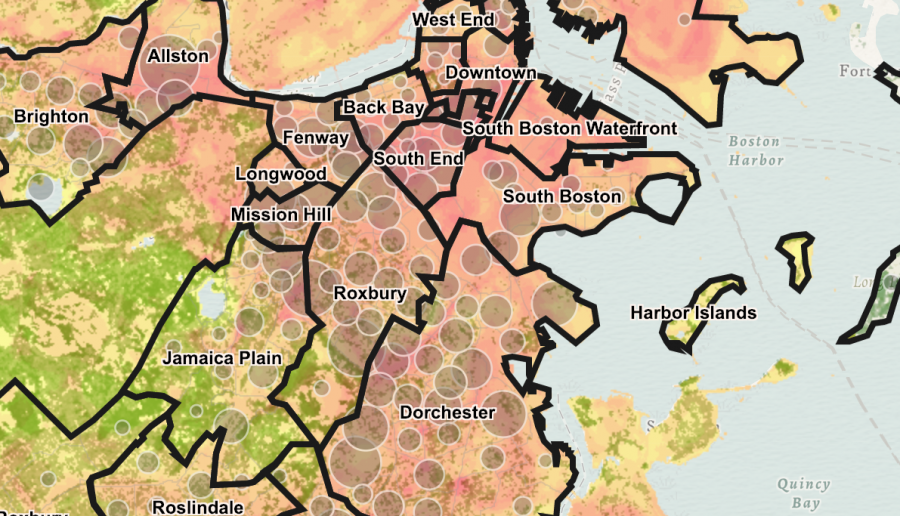

For Jim Vrabel, 70, Mission Hill in the 1970s was a patchwork of local activist organizations. Each was fighting to address a separate issue, but ultimately united by one main goal: improve living standards for the neighborhood’s multi-racial, predominantly working-class residents.

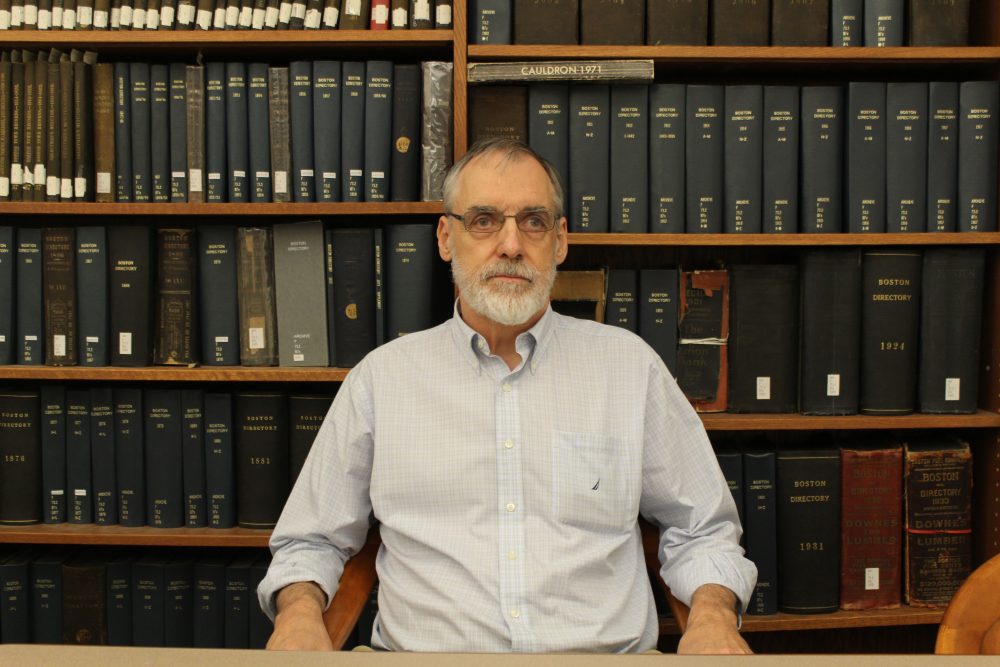

“Everybody was in there own mini-neighborhoods,” said Vrabel, an author and local historian who spent 25 years working in the mayor’s office, the redevelopment office and the Boston School Committee. “But they knew people from the whole Hill. And we worked together, sometimes competed, sometimes cooperated.”

After graduating from Northeastern University, Vrabel bought his first home on Lawn Street in 1974, placing him in an area of Mission Hill known as “the back of Hill.” It was defined then as the land between the New England Baptist Hospital and Heath Street.

It was here that Vrabel helped found the Back of the Hill Community Corporation, which organized tenants to fight against institutional expansion from the Lahey Clinic and the Ruggles Baptist Church. The clinic and church had purchased land in the neighborhood, demolished hundreds of homes and, as Vrabel said, “left a kind of wasteland of vacant lots.”

His group was one of several that formed in Mission Hill during the ‘70s in response to similar threats. The Roxbury Tenants of Harvard fought encroachment from Harvard University. Meanwhile, Mission Main Public Housing organized themselves to combat the growing threat of displacement in their part of the neighborhood..

“It was an exciting time,” said Vrabel. “There were meetings every night, you could be out until midnight every night at neighborhood meetings if you wanted to. And some people were.”

After protesting outside U.S. Senator Edward Kennedy’s office and gaining the support of Mayor Ray Flynn, the Back of the Hill Community Corporation successfully pressured the Lahey Clinic into selling their land which. The areas were subsequently developed by the builders and bricklayers union, who built hundreds of housing units on the site.

While Vrabel believes they helped solve an issue, their actions have had unintended consequences. “In some ways maybe we did too good of a job,” he said. “This ushered in the gentrification and the influx of college students that has happened in Mission Hill since.”

It is a fine balance, one Mission Hill is still trying to find.

“The struggle is to not only make the neighborhood better for poorer, working class people,” he said, “but to also make sure poor and working class people can continue to live in that neighborhood.”

About this project

The Scope’s student journalists spoke with community members in Mission Hill. #MissionHill100 is a collection of their stories.