Since President Donald Trump’s return to office in January, and his administration’s focus on immigration enforcement and deportation, some Bostonians are increasingly eager to show their support for immigrant communities.

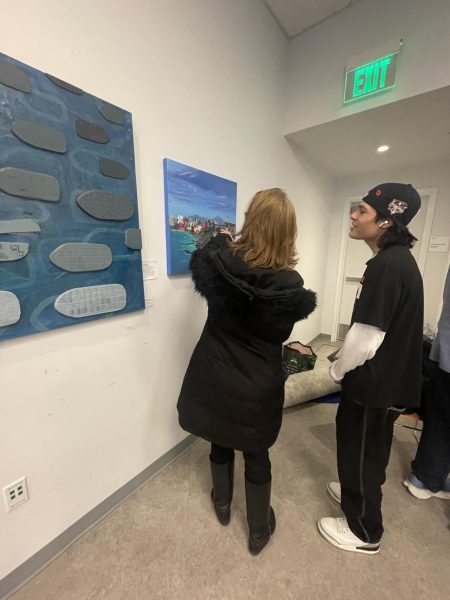

In early February, over 60 attendees packed the small space at Boston Public Library’s Roslindale Branch for an opening reception of an art exhibition, “Immigration: Joys and Hardships.” Filled with work by artists from Morocco, India, Puerto Rico and more, the show is made all the more poignant by the artists’ own immigration stories printed on the walls.

Vivienne Shalom, one of the exhibit’s curators, kicked off the event with a statement on the show’s political importance.

“In these times,” she said, “It’s great to know that Roslindale doesn’t just welcome immigrants. It celebrates them.”

Poet Henrietta “Queen” Hodge opened the program by singing one of her pieces to the tune of “God Bless America.” The song told the story of one of her relative’s journeys from Cuba to North Carolina and his eventual move to Boston.

A panel discussion with three exhibiting artists followed the reading. In her speech, artist Ankana spoke of the pressures and pain of assimilating to a new country. She is Axomiya, an ethnic group from South Asia, but after moving to the United States she found it hard to explain her identity to Americans and ended up oversimplifying it.

“I tend to just be lazy and say I’m from India,” she said. “Let’s be real, a lot of us assimilate and we lose a lot of ourselves in that.”

Ankana’s art on view is a painting called “Journey Home.” It’s a kaleidoscopic vision of red, black and yellow, containing words from her native language that symbolize her journey toward self-acceptance.

Ankana admitted that she can no longer read or write in her own language—a consequence of assimilation. She had to look up and re-learn the words that she wanted to include in her painting.

Next, Watertown resident Adnane Benali spoke about his life experience and its influence on his art practice. Decades ago, he moved to the U.S. from Morocco and spent his college years in Boston.

Benali’s art takes the form of intricate miniature doors, each one hand-crafted with American cedar wood. His use of local wood—combined with the Moroccan architecture—is a clear message to viewers that even in a new place, memories of home remain.

Benali encouraged visitors to look at the doors not just as art, but as symbols of shared humanity.

The event closed with two poetry readings, including Nancy Marks’ piece, “Reflection/Confession,” a poem with antifascist sentiment comparing her mother’s experience hiding in World War II-era occupied France to United States deportations in 2025.

“Forgive me if I forget it’s Massachusetts and not occupied France,” she recited. “When I rise, I hope I will like the person in the mirror.”

In an interview after the event, attendee and local artist Jameel Radcliffe said he was encouraged by the turnout and inspired by the artists on view.

“There’s a lot of people who showed up today,” he said. “I think it’s very exciting. There’s a lot of interesting work from artists I’ve never met or seen, which is amazing.”

Radcliffe even experienced a full-circle moment at the opening. A teen artist, Yaron Rodriguez, who he mentored through the nonprofit Artists for Humanity, had a painting called “San Juan” on view. It was Rodriguez’s first public exhibition outside of the program. He’s now starting to apply to colleges and is even considering the arts as a field of study.

Artists at the event were thrilled to have their work on view. Yet immigration is a sensitive topic, especially now, and attaching an artist’s name to art in a public space comes with some risk.

“We were a bit nervous about what was going on in this country,” Shalom said in an interview, “but we decided that it was really important at this time to share these stories.” The team, which also includes Phyllis Bluhm, Mary Russell and Vicki Bocchicchio, was cautious in its approach and sought to avoid putting artists at risk.

The exhibition, which runs through the end of March, demonstrates the commitment of the library and the event curators to showcase work by immigrants, even during tense times.

Correction: A previous version of this incorrectly identified the person who made the opening statement at the event.