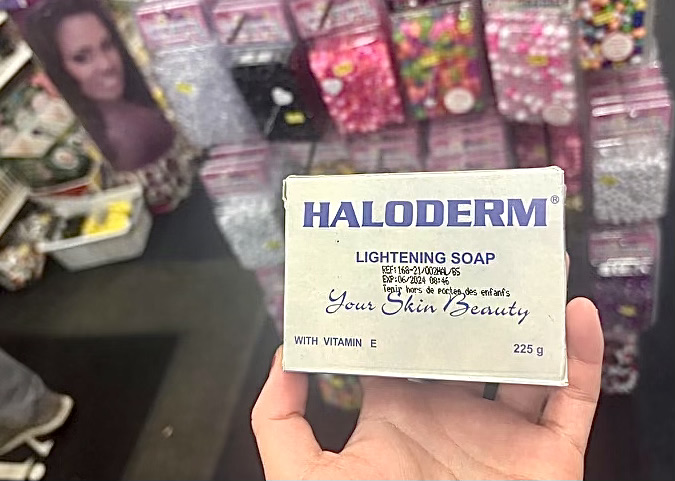

In the summer of 2020, Gabriel Andre Augustin purchased Haloderm clobetasol propionate 0.05% to lighten his skin. Kiki Beauty Supply, a company that has three locations around Boston, authorized the sale.

For eight months, the 26-year old from Cambridge applied the cream. On March 2, 2021, he was admitted to Massachusetts General Hospital for symptoms undisclosed in official public documents. According to an autopsy cited in a lawsuit filed by Augustin’s sister, Shanna Pringle, Augustin died the next day from cardiac dysrhythmia – a condition which can lead to heart failure – in association with chemical burns.

Pringle sued Kiki’s Hair City Inc., Kiki Beauty Supply Inc. and Beauty Supply Supermarket Inc. on behalf of her late brother. She charged that the businesses were responsible for Augustin’s wrongful death and requested monetary compensation for his suffering and medical bills, which totaled more than $50,000, according to court documents. On Dec. 19, 2024, claims against Kiki’s Hair City Inc. and Kiki Beauty Supply Inc. had been dropped. But claims against Beauty Supply Supermarket remain in effect.

Pringle could not be reached for comment and her lawyer Jordan Belliveau declined to comment.

Augustin’s death, though not yet verified to be a direct result of using a skin-lightening product, is not the first report of someone suffering a health crisis after using skin-lightening products.

All around the world, especially in Asia and African countries, people of color seek to lighten their skin for cosmetic reasons – under the pressures of a phenomenon called “colorism,” which is discrimination based on skin tone – in particular, favoring lighter skin tones. Unaware of the dangers these unregulated products may pose to their health, customers like Augustin can easily purchase prescription-grade products like Haloderm clobetasol propionate 0.05% over the counter in stores like Kiki Beauty. Even though a prescription is required for this drug in the U.S., stores often carry imported products from countries that have fewer regulations.

Experts say that the skin-lightening market is taking advantage of people of color, and putting their safety at risk, often unknowingly.

“Skin-lightening products exploit these vulnerabilities and prompt communities of color to chase after [a Eurocentric ideal] using unhealthy means,” said Chloe Gao, a visiting scholar at Boston Children’s Hospital, who studies double-eyelid surgery and other cosmetic interventions in East Asian populations.

In 2021, the global market for skin-lightening products was valued at $9.96 billion, according to a study by Grand View Research. The same study predicts that the global market for such products will reach $16.14 billion by 2030.

Kimberly Norwood, professor of law at Washington University, says that in a society where white people are at the top of the social hierarchy, skin-lightening products appeal to people who believe that lighter skin increases their likelihood of gaining certain educational, financial and social privileges. Black and Hispanic Americans are less likely than white Americans to complete four or more college years. They are also less likely to receive a promotion.

“It is often impossible to tell what a person’s ethnicity is. [But] it’s not hard to choose light over dark,” Norwood said.

Clobetasol, typically used to treat eczema, psoriasis and inflammatory skin diseases, is a topical steroid used on thick-skinned areas due to its potency and is a common ingredient in skin-lighteners. Another skin-lightening drug is hydroquinone, most commonly used for treating melasma and hyperpigmentation. Both medications have side effects that include burning, stinging, itching, irritation, dry skin and thinning of the skin. Both drugs interfere with the body’s immune response and or melanin production.

“One of the problems with long-term use of hydroquinone is it can actually cause irreversible abnormal pigmentation. I hardly use hydroquinone anymore,” she said. When she does, she prescribes Tri-Luma cream, which, in addition to hydroquinone, contains fluocinolone and tretinoin. Those ingredients help with adverse side effects by reducing irritation and skin turnover.

The risks are so high, Burnett said, that when she does prescribe the drug for things such as melasma and age spots, she requires her patients to follow up in person for refills so she can monitor potential misuse.

Burnett says that there is a market of illegal skin-lightening products in the U.S. that tend to be sold in smaller businesses, chains or corner shops. For example, most of the lotions and creams sold at Kiki Beauty Supply are $8-$20.

Nigerian citizen Oluwabunkunmi Akomolafe, 20, started using skin-bleaching lotions and soaps four years ago. Akomolafe’s friend had recommended these products and once she started using them, her confidence was boosted and she felt she couldn’t stop.

“I liked how it made my skin pop at first – the brightness. I liked how it made me feel,” Akomolafe explained, adding that she kept buying similar products for the next three years to lighten her skin. The practice didn’t seem harmful or unusual, she said, because it is common where she lives.

It wasn’t until she went on vacation and forgot to pack her creams and soaps that her body became extremely itchy and she knew something was wrong. A year ago, she made the decision to stop using the skin-lightening products. It has been a tough transition period. In addition to the sudden onset of burns, stretch marks and itches, she became “very very very black. Extremely black.” Now, she is in the process of repairing her skin by using lotion and aloe vera and avoids skin-lightening products.

“I feel healthier, like I’ve [repaired] my damaged skin barriers. Even though it is hard to accept how I am now, I made the right decision,” Akomolafe said, who is currently a student at Federal University Oye-Ekiti studying English and literature.

Eliza Vargas, a psychology major at Northeastern University, grew up with a father whose skin was much darker than hers. She considers herself white-passing and believes it has contributed to some of her professional success.

“One thing I’ve noticed growing up is that I was socially more accepted than my dad when it came to professional settings,” she said. Her dad is a mechanic, while she is studying to be an engineering psychologist.

She said that colorism is a thought that follows her everywhere she goes, including when she moved to Boston for school last year. She remembers a story her New Jersey friend, who is Black, told her when they met in college. Her friend’s sister was using skin-lightening products because she didn’t like how her Black skin made her feel “dirty.”

Vargas doesn’t agree that being Black means dirty, but explained that was how colorism had affected her friends. A continuing theme in her mind is that people will chase success no matter what, and success means being light-skinned.

Those privileges are not exclusive to the United States. In Nigeria, Akomolafe faces similar challenges as a Black woman.

“Nobody wants to be Black, dark. People are not confident enough in their Black skin, which is why most people bleach,” Akomolafe said. “I’ve seen too many guys in my area tell me they can never go for a Black-skinned woman.”

Such insecurities are profitable for businesses and experts believe the beauty industry is complicit in perpetuating colorism. Skin-lightening products are just one manifestation of colorism.

Gao, the visiting scholar at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, conducts interviews for her research. One interviewee’s family owns a beauty store and said skin-lightening products are in high demand and have to be constantly restocked. Gao worries that if these beauty standards continue, not everyone will have access to skin-lightening products, which could exacerbate the psychological stress that the consumers are experiencing.

Si Wook Yoo, owner of Kiki Beauty Supply where Gabriel Andre Augustin shopped for his cream, said he was not aware that any of his products contained potentially harmful chemicals. He removed the product Augustin used from shelves of his three stores once he learned of the lawsuit against him. His lawyer, Christopher Fitzgerald, could not be reached for comment.

His store on Washington Street in Roxbury is filled with hair creams, hair extensions and various beauty products. About halfway down on the left, on a shelf next to hair products, is his inventory of skin-lightening creams and gels. With names like WHITESECRET and Clair White, some promise “absolute results” while others advertise “skin toning.”

A number of the products in this section contain non-English ingredient labels, which is a violation of FDA regulations, said Nicole Hirschmann, a case consultant at Boston-based Morgan and Morgan law firm, which specializes in cases involving personal injury and defective products.

Burnett, the Wellesley dermatologist, said she is particularly concerned with social media’s role in spreading harmful messages about skin color.

“Skincare was always a big business, but it’s exploded in the past few years. And they’re targeting younger individuals. It’s driven by people trying to make money. And a lot of these things are unnecessary for people to use, especially at a young age and sometimes harmful,” she said.

Gao shared a similar sentiment: “It’s a vicious cycle. You’re widening health disparities mentally and physically by obtaining and using these products.”

Standing in the skin-lightening lotions and soaps aisle, Yoo spoke about the impossibility of checking each of his 30,000 products for safety and that wholesalers and manufacturers that supply products should be responsible. But Hirschmann says otherwise.

“If an owner has over 30,000 products, it’d be way more than a small business. He should be way more involved in knowing what his products are,” Hirschmann said. “It is your responsibility as a person selling the product to make sure it’s safe.”