Massachusetts has seen an unprecedented spike in book challenges across public schools and libraries, overwhelming library organizations and inciting conversations state-wide about free speech and expression for youth.

“There is a level of intense activity we have not seen before,” said Jennifer Varney, president of the Massachusetts School Library Association, or MSLA. “And in Massachusetts, that’s really rare.”

This past school year, there have been a total of 23 official book challenges across the state. Varney did not specify which districts experienced the challenges, but said she is not aware of any formal ones filed in Boston.

Historically, the MSLA has not kept track of book challenges, and to date, there is no official database of them in Massachusetts. When individuals contact the MSLA about challenges, their inquiries are redirected to the American Library Association, or the ALA, a national organization based in Chicago. But even the ALA’s records are limited to self-reported challenges, meaning there are likely more challenges being made that neither organization is aware of.

The MSLA began tracking book challenges in early October, after seven challenges had been filed. Across the association’s seven school districts, 15 titles have been targeted.

Titles with three challenges:

- “Flamer” by Mike Curato

- “This Book is Gay” by Juno Dawson

- “All Boys Aren’t Blue” by George M. Johnson

Titles with two challenges:

- “Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out” by Susan Kuklin

- “Gender Queer” by Maia Kobabe

Titles with one challenge:

- “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian” by Sherman Alexie

- “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison

- “Felix Ever After” by Kacen Callendar

- “The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas

- “Lawn Boy” by Jonathan Evison

- “Let’s Talk About It” by Erika Moen and Matthew Nolan

- “Not My Idea: A Book about Whiteness” by Anastasia Higginbottom

- “Out of Darkness” by Ashley Hope Perez

- “The Poet X” by Elizabeth Acevedo

- “Push” by Sapphire

Collectively, the major themes in these books are of gender identity, sexuality and racism – sensitive topics which have reinforced the MSLA’s decision to start tracking challenges, said Varney.

“To me, the data is important because I think if you look at the list of titles, it’s clear that certain aspects of certain voices are being challenged,” Varney said.

ALA president Lessa Pelayo-Lozada said she also observed similar thematic trends at the national level. From personal experience, she said books about identity are especially important for youth, saying she lacked proper information about her background and ancestors as a mixed-race native Hawaiian woman.

“I’m born and raised in California, but I am native Hawaiian, which is very confusing to a lot of people, right? And a lot of people also don’t have access to that information to be able to understand that,” she said. “So, when we have access to that information, then we can really start to identify the humanity in one another and how our intersectionality is combined so that we can be whole and together.”

Many of these challenges are also coming from larger groups as an organized effort, which is a significant change. In the past, a community member would come across a book they found offensive, whether from browsing their local library or seeing their child brought it home from school, and then would submit a challenge.

Now, nationwide organizations like Moms for Liberty, for example, have generated lists of books to challenge, which may vary by state and chapter. Moms for Liberty aims to educate parents and hold politicians accountable for the content being taught in schools.

“We want transparency,” said Tia Bess, the national director of outreach for Moms for Liberty. “I mean, there are so many things that we want for our kids, and we’re working slowly on the local level by educating our parents and empowering them that they have rights. They have parental rights.”

Librarians, like Andrea Fiorillo, are frustrated by how these challenges arise, as providing diverse books is simply part of their job. Fiorillo is the Head of Research & Reader Services at Reading Public Library and also serves as co-chair of the Intellectual Freedom and Social Responsibility Committee at the Massachusetts Library Association.

“Not only are they different in nature — like it might not even be someone in your community that’s making a challenge — but there’s also a sense that these outside groups are using libraries and schools very much as a culture war, like we’re being kicked around like a culture war ball that, of course, we are not here to be,” Fiorillo said. “We really try to provide materials and programs, services and curriculum that really meet the needs of the entire community.”

Recently, there have also been instances where librarians have been harassed or bullied by parents in order to have books removed.

The Scope spoke with a public-school library teacher in the Greater Boston area, who was part of an ad hoc committee last year to address a challenge against both “Gender Queer” and “This Book is Gay.”

In this case, the titles were ultimately kept on the school shelves, and there was also an outpour of community support for the books during a school committee meeting. But at the meeting, the teacher said the most heartbreaking moment was seeing how the hatred toward these books affected the students:

“I was sitting right behind some of my students when the people got up and spoke about how awful these books are,” the source said. “And I looked back, and they were like flinching because it’s almost like someone was leveling that criticism to them as a human being.”

The challenging and banning of books has recently faced controversy throughout the country. In addition to many wanting greater representation in the media, those against book banning say it is unconstitutional and a form of censorship, since school libraries are children’s primary resource for reading materials, according to Varney.

Others, however, find these books unsuitable for their children and desire more control over what information their children can access at a young age, especially surrounding topics like race, gender or sex. Bess, for instance, wants to be able to discuss those themes with her children herself, rather than having a book teach it to them first.

“We are a two-mom household. I’m a lesbian; my wife is a lesbian. We are conservative, and we’re in a committed relationship. I’m a Black woman — I’ve always been Black,” she said. “However, there’s conversations that I need to have with my children. My children are biracial, so I don’t want someone else’s biased opinion to affect how my children view the world.”

Bess also understands that not every child may be able to have conversations like this with their parents, and that it’s not her place if other parents want their children to be able to read whatever they like. She personally desires a more nuanced solution, like having books with more mature content behind a library counter that requires a permission slip signed by parents to access it.

“When you go to some schools, it’s K-8. How should a kindergarten have access to the same book learning about sexual development?” Bess said. “And they’re in kindergarten. That just doesn’t make sense to me.”

One of the books Bess is referring to, which has caused the most uproar among parents, is “Gender Queer.” This book is an award-winning graphic memoir about author Maia Kobabe’s personal experiences in exploring gender and sexuality, and the ALA deemed it the most challenged book in 2022 and 2021 nationwide. In the book, there are illustrations of sexually explicit content, including an oral sex scene, which is at the core of many complaints about the book’s accessibility to children.

However, despite the rise in these challenges, a majority of the nation is actually opposed to banning books. An ALA study from March 2022 even found that 71% of U.S. voters opposed book banning in public libraries.

“This is a vocal minority of individuals. This is not a mass wave,” Pelayo-Lozada said. “It’s just that because it’s an organized effort, because they are very loud, it feels like more people support this agenda.”

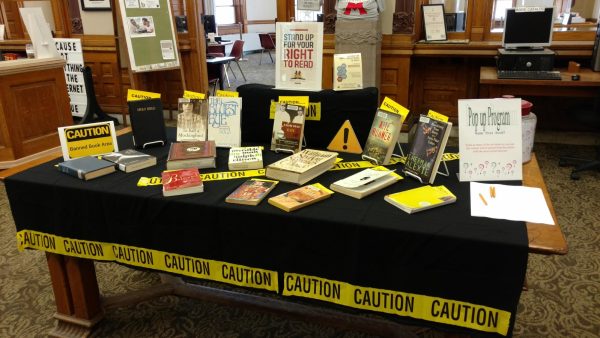

Boston as a city has generally embraced the inclusion of these books. The Boston Public Library even participates in “Banned Books Week,” an annual event hosted by the Banned Books Coalition, where libraries highlight stories that are typically challenged and draw more attention to this issue.

Librarians understand that parents may have concerns, but feel that their individual issues with these books should not influence how accessible these titles are to other youth.

“I think a lot of people think that if a book is in a library, they have to love it,” Varney said. “You don’t have to love it. You don’t have to love every book in the library, but you can’t take it away from other people who might want it.”