Blue Hill Avenue: a lesson for Boston activists 50 years later

“Massachusetts’ capital city, with its lofty aspirations and serious shortcomings, its principled pluralism and rabid racism, may be paradigmatic of America.”

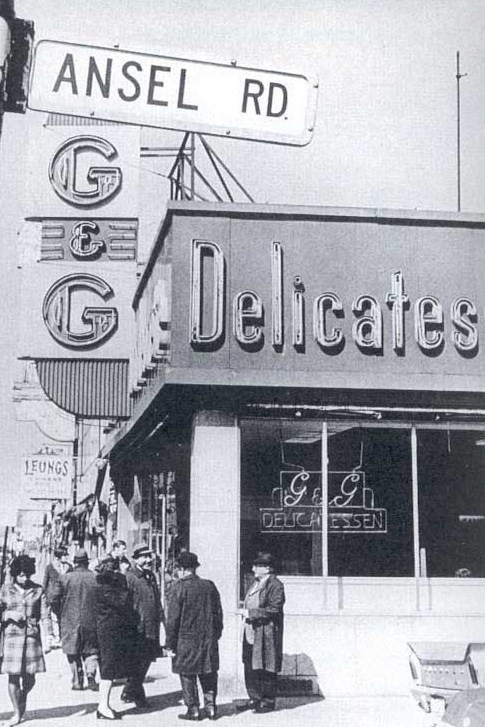

Photo: Public Domain

Until 1968, the culinary and political heart of Boston’s heavily Jewish Blue Hill Avenue was G&G Deli. From US presidential candidates to local celebrities, G&G was the place to be seen and heard.

Lew Finfer, a longtime Boston organizer and activist, quips that the city is like “the Deep North,” referencing its long and sordid history of societal inequality and racial injustice.

Finfer described the impact of redlining and other “well-intentioned” policies of the 1970s throughout America in a 2019 Boston Globe article. The piece also underscores how these policies shaped legacies that still loom large over poor and vulnerable communities in Boston. They remain at the forefront of the minds of community activists battling skyrocketing rents and once integrally familiar but now alien and unwelcoming main streets in a post-pandemic era of economic uncertainty.

Today, Blue Hill Avenue is a neighborhood in a city only superficially removed from a decades-old history of racial segregation, which still shapes its rapidly gentrifying foundations. Yet, as Levine and Harmon write in “The Death of an American Jewish Community,” “Massachusetts’ capital city, with its lofty aspirations and equally serious shortcomings, its principled pluralism and rabid racism, may be paradigmatic of America.”

But its current problems are rooted in the 1960s and ’70s, when the neighborhood, a working-class Jewish area, fell victim to the rapacious ‘blockbusting’ interests of the banks and their pet real estate agents.

After the assassination of Martin Luther King in 1968, the Fair Housing Act was taken up to ensure more equitable lending practices and home ownership for communities of color. The Boston Bank Urban Renewal Group focused this lending exclusively on Black families in neighborhoods around Blue Hill Avenue. The inevitable inability to service these expensive mortgages or pay for dubiously regulated renovations led to early bank foreclosures and abandoned homes, a devastated community, and a downward trend of economic instability and entrenched segregation yet to be bucked.

The impacts of these policies not only devastated communities at the time but persist today. They are visible on the street corners around Blue Hill Avenue and in the degradation of the historic Black-Jewish civil rights alliance, an issue intensified in today’s discourse through the recent behavior of influentially ignorant actors with malicious intent. However, projects such as Main Street America run initiatives in neighborhoods like Boston’s Roxbury to revitalize historic communities and commercial districts and recognize, listen to and elevate the voices of their affected residents. Created as a program of the National Trust in 1980, Main Street’s work focuses on combating the harmful impacts of urban sprawl on the physical character and economies of communities.

Delaney Murray, development, fundraising, and communications associate with the Roxbury chapter, told me, “When you have a strong main street, you have a strong community,” detailing her organization’s reinvestment and fundraising work to bolster the minority-owned businesses and institutions of Dudley Square.

Murray said, “Roxbury is isolated. It’s a wonderful community, passionate and boisterous, but they are an island in this area of Boston, a victim of outside forces proliferating gentrification and trying to minimize its role. I want to push back on that and make sure Roxbury is here to stay.” She added, “If we lose cultural identifiers of Boston like Roxbury, we’re going to lose the heart of the city. If we don’t start focusing on these communities, they’re going to disappear forever.”

While the destructive forces of 50 years ago are still with us, community activists like Lew Finfer and affordable housing and small business initiatives like Main Street America continue to do much to revitalize the inner city and reduce the racial wealth gap. Long may their fight continue.