Public employees and social media: what stays private?

“There’s no such thing as privacy on social media, even on a private page.”

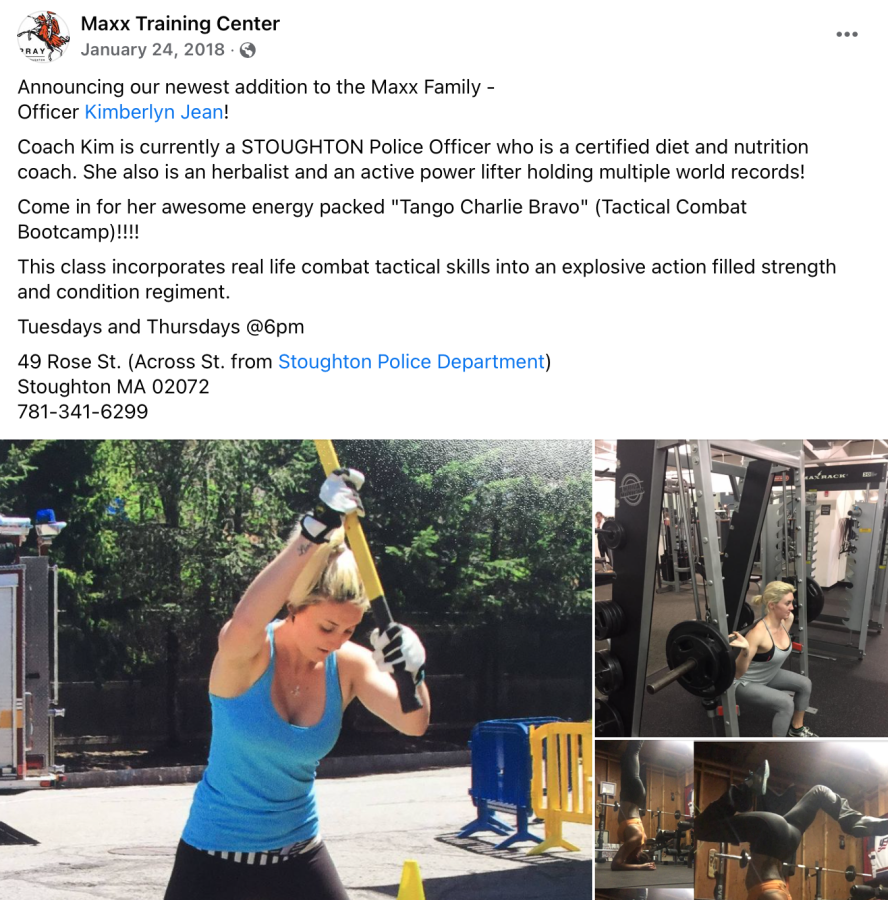

In the pictures posted in 2018 on Facebook, Maxx Training Center advertised their newest fitness class, “Tango Charlie Bravo,” phonetic alphabet for “Tactical Combat Bootcamp,” taught by their newest employee, “Officer Kim.” But this was no ordinary advertisement, as Kimberlyn Lydon, the employee in question, was also a police officer with the town of Stoughton.

The conflation of the two jobs in such a public manner was seen as a “potential ethics violation” by Town Manager Marc Tisdelle, prompting him to fire the five-year employee without opportunity for remediation. After multiple attempts to reach them, Lydon and Tisdelle declined to comment on the matter.

Now Lydon is suing the Stoughton Police Department and the town of Stoughton for damages on six counts, two of them involving wrongful termination in an ongoing demand filed in Norfolk County Superior Court on Oct. 13. Deputy Chief Brian Holmes of the Stoughton Police Department referred to their lawyer, Thomas Donohue, for comment. Reached by phone at his office, Donohue declined to comment on the department’s behalf.

“Being a police officer is public knowledge,” Lydon, 31, of Canton, wrote in defense of herself as part of the statement filed in Norfolk County Superior Court. “What the training center posted was acceptable. And if it wasn’t [I] did not have control over it.”

For employees like Lydon, social media has blurred the line between their public jobs and private citizenship, confusing what their First Amendment rights permit them to say with what directly reflects on their institution. A social media slip-up means more than mere embarrassment for public servants across the country — it can impact their reputations and jobs because, in some communities, there seems to be no room for slip-ups or even mistakes of judgment.

“There’s no [legal] restriction for an employer to survey their employees. I don’t know of anything that would preclude that,” said Alan McDonald, legal counsel for the Massachusetts Municipal Police Coalition, a statewide alliance of police unions. “The question of ‘should they be surveilling other social media’ is not the best practice, but it’s not illegal.”

Lydon is not the only police officer with social media under scrutiny. Nicholas Holden, a former Massachusetts state trooper, faced an 18-month suspension and termination for a post on a private Facebook group for Massachusetts State Police that read, “Don’t be a [expletive]. Go and kick some [expletive] … Holden #3005.” At the time of the posting, Holden was stationed at the Brookfield barracks in uniform and in front of a state police vehicle. Holden is now suing his former employers to “be reinstated in his prior rank and position” in an ongoing case filed in Suffolk County Superior Court April 4.

“Trooper Holden stated that he did not intend for his post to reflect negatively on the State Police,” according to transcripts provided in the lawsuit. Holden also said in the transcript that he was “one hundred percent confident” that the general public would never view the post. Experts say this assumption isn’t enough to shield public employees from the consequences of being the subject of unbecoming content on social media.

“There’s no such thing as privacy on social media, even on a private page,” explained Jonathan Downes, a labor and employment attorney at Zashin and Rich, L.P.A., in Columbus, Ohio. “Public employees leave some of their constitutional rights at the door in their service of the public.”

David Officer, Officer Holden’s attorney, said via email that he and his client have no comment on the matter. The Massachusetts State Police could not be reached for comment.

Social media complicates how statements are viewed in a courtroom setting, making them harder to classify as public or private.

According to McDonald, this has roots in the 1968 Supreme Court case Pickering vs. the Board of Education, where a public school teacher was fired for a letter to the editor complaining about a school board decision. In an 8-1 decision, the court ruled that Pickering’s termination violated his First Amendment right to free speech.

“[Pickering vs. Board of Education] began that interesting balancing act between whether [speech by public employees] is a matter of public concern vs. internal concern,” McDonald said.

With social media, the lines are blurred even further. According to legal professionals, the courts primarily consider social media postings to be that of a private citizen unless there is a link to someone’s job duties or responsibilities. A link to their job automatically associates them with the public sector with public employees.

“Whether speech by a government employee is protected by the First Amendment depends in part on whether it was made in the speaker’s role as a public employee — in other words, pursuant to his or her official duties — or as a private citizen,” said Caroline Davis, an associate attorney in state and federal employment at Zalkind, Duncan and Bernstein, L.L.P., in Boston.

However, McDonald said that police departments and unions have strict guidelines on what is considered appropriate beyond the courtroom. For instance, Holden’s department prohibits “speech containing obscene or sexually explicit language,” according to court transcripts. Holden, nor his attorney Thomas Donohue, would comment on the case. On Aug. 5, 2020, Holden was dishonorably charged but was also the subject of four internal affairs investigations beginning in March 2014, before the post was even made.

“People tend to confuse violation of rights with policy,” said McDonald. “Employment isn’t intruding on free speech when we have the right not to work for that employer.”

In August, the Washington State Criminal Justice Training Commission, or CJTC, a council that establishes standards and instructions for criminal justice professionals, announced that officers must “consent to and facilitate” a review of their social media accounts. This required all new hires to hand over access to their social media accounts, including private ones, to the CJTC for review or face termination.

Darren Wright, the public information officer of the Washington State Patrol, told The Scope this move originally was to maintain transparency between public servants and the communities they serve.

“We hold our troopers to a high standard of conduct, both on and off duty. On social media, and with inappropriate behavior in general, our troopers need to know that they live in a glasshouse. We need to maintain respect from the public with no hypocrisy involved,” said Wright.

As of Nov. 20, this move has now been walked back due to “confusion, frustration and anger” from those involved, according to a statement from the CJTC. Now social media reviews are only to be used for specific cases related to investigations per state law.

While this is only in effect in Washington, Wright said there is a chance that social media reviews within police departments will become more customary, creating a commonality in how the profession is viewed.

“Things like this tend to spread [across the country]. Our profession is under scrutiny right now, and I hope the profession everywhere is able to maintain a level of respect from the public,” Wright said.

This does not mean that police departments will censor their employees. McDonald explained that as long as officers understand and obey the standards of ethics within their respective departments, they shouldn’t worry about their social media postings.

“I advise all union employees to be careful and to understand lawful first amendment expressions… But sometimes it’s easier to cite the rule than to apply it,” McDonald said.

This does not quite ring true for situational cases like Lydon’s, where she was not at fault for creating the post. Reached over email, Lydon, who owns Bare Studios in Canton, where she now works full-time as a personal trainer, refused to comment because her ongoing litigation against the Stoughton Police Department is close to its end.

“I have been fighting this for over 3 years and would like to close it without anything getting jeopardized,” Lydon said in an email.