Boston’s Generation Z population want somewhere to be queer

Decades ago, Boston’s gay nightlife thrived, now almost depleted, queer youth search for public spaces to build community

Photo: Allan Leonard

Photo of the LGBTQIA flag outside of the Boston Public Library.

Kester Messan, 23, didn’t come out as gay until he arrived at Williams College in 2017.

Born in Togo, he and his family moved to Boston when he was six years old, first settling in Roxbury, then Cambridge. Growing up, he became heavily involved in Boston’s theater and dance community, spaces that he says are often coded as queer. But he still wasn’t out.

For him, it felt like he didn’t have a sexuality — people asked him if he was gay in middle school, but in high school, nobody brought it up. He lived in limbo. He knew that he was attracted to men and never hid from queerer- or feminine-performing spaces, but he wasn’t going to tell anyone. When he moved out of Cambridge and away from home, he finally grasped his identity.

“There’s a reason why I didn’t come out until I left,” Messan said. “Why is it that Cambridge is this amazing bubble, this amazing utopia? But I didn’t feel safe enough or valid enough or affirmed enough to come out.”

During his first two weeks at Williams, he had his first hookup with a guy, which affirmed his sexuality. He felt like he could finally experience what straight people usually found much more quickly: intense, flirtatious banter and a natural connection. After that, Messan realized he couldn’t hide who he was anymore.

Now that he’s out, graduated and living in Brooklyn, Messan says he still doesn’t seek out queer spaces when he comes back to visit his family in Lynn, Mass. — mainly because the options are sparse and not made for creative-minded people like him.

“We all have our own assumptions of what Boston is and how it makes us feel and what we feel like we can get out of it,” Messan said. “In the same way that I feel like Boston, right now, doesn’t have a lot to offer queer people, I feel the same way about creatives and people making art. So every time I return home, I’m not excited to find community and explore. I know what Boston has to offer.”

Finding physical spaces for younger queer people in Greater Boston is often a struggle. With a handful of nightlife options like Club Café or DBar and a lack of a designated “gay neighborhood,” there’s nowhere that younger, Generation Z queer people can gather or find one another. If you’re under 21, the options are even slimmer.

According to a Gallup poll in 2020, one in six members of Generation Z — those born after 1997 — identify within the LGBTQ+ community, making it the queerest generation to date. Many college-aged youths fall into this category, and despite Boston housing 35 colleges and universities, queer people have few options to go out and gather with one another. Cities like New York City and San Francisco boast vibrant LGTBQ+ populations, each with queer havens like the East Village and the Castro, respectively, but Boston has no reputation up to this caliber, potentially to the detriment of younger generations.

“When kids, especially teenagers [or] college students, are told that they can be themselves, but they don’t see anywhere to feel themselves with other people like themselves, it can perpetuate the feelings of isolation … that have always existed,” said Kristopher Cannon, an associate teaching professor at Northeastern University and an expert in queer theory, who uses he and they pronouns.

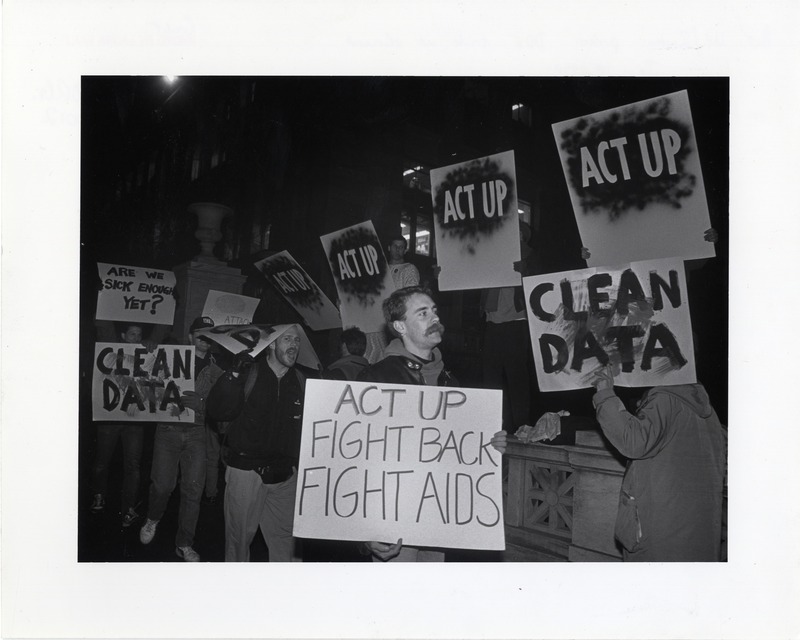

While historically, especially between the ‘50s and the ‘70s, Boston’s gay nightlife scene was booming with bars like Sporters in Beacon Hill and Buddies in Back Bay, the number of spaces has declined. The gay rights movement was the first of many blows to gay bars, along with the AIDS crisis and the rise of the internet, said Mark Krone, a board member of The History Project, a nonprofit that documents New England’s LGBTQ+ history.

“You didn’t have to go to a bar just only to meet queer people. You could go to the gay men’s softball team, the lesbian softball team … the Massachusetts Lesbian Gay Political caucus. There were organizations for Latino gays … Asian American gays and Black gays,” Krone said. “There were a lot of non-bar activities starting up … so you had other ways to be gay than just going to a bar for a long time. The bars were it — that’s all you had.”

However, as a white person, he recognizes the limits of his perspective. “It was easy for me as a white male to say, ‘Oh, gay bars were such a refuge. We could all exhale and be ourselves.’ True, to some extent, but not for everybody because you could be Black and go into a gay bar and nobody would really talk to you because you’re not what they were looking for,” Krone said.

Today, Cannon says spaces are still often made for cisgender men with no counterpart for women or transgender people, who are all active members of the LGBTQ+ community. In the United States, The Lesbian Bar Project found in 2020 that there are only 21 lesbian bars, with some bars closed since the project started. Cannon says they frequent places like Club Café, a gay club in Back Bay, but the options are still sparing.

“Boston, for example, as much as there is sort of a liberal theology, politically, that kind of floods through the city and maybe more broadly the state, there’s a way in which, in my mind, a lot of things are lip service to ideas over practice,” said Cannon. “Boston itself has felt very lackluster for there being community spaces, and when they do emerge, they’re either sort of mixed-bar spaces that in some cases have trouble staying open.”

As an immigrant, though, Messan’s perception of Boston is informed through the lens of his parents, who came to the U.S. to give their children a better education. And that’s what Messan feels is Boston’s priority, a deep focus on its student-rich community and corporate environment. “Everything else — pleasure, fun and creativity — those things kind of take a backseat,” he said.

However, he recognizes that queer spaces in Boston exist, but he feels that spaces aren’t doing enough outreach, especially to younger people.

“They need to be actively working to reach out to people like myself, and I’m sure a lot of young people growing up in Boston desperately needed those spaces,” Messan said. “And so, just existing isn’t enough. Clearly, the outreach or the marketing or the PR wasn’t strong enough to reach me.”

As soon as he graduated from college and moved to Beacon Hill in 1973, John Kane, now 72 and a lecturer in graphic design at Northeastern University, found a sense of community at gay bars throughout Boston. Kane and his friends frequented Sporters, a gay bar on Cambridge Street on the north slope of the hill.

While queer nightlife may seem sparse today, the 1970s was a vibrant time for Boston’s gay community. Kane and his friends would come together at bars like Sporters, Buddies in Back Bay and The Boston Eagle in South End, often dancing the night away.

“We would go, god, three nights a week probably, to go out dancing,” Kane recalled with a sigh, “just because it was terrific fun, and it was the ‘70s, and disco was just starting.”

For Kane, what he loved about going out was the feeling of freedom, the ability to be yourself in a gay bar. “Part of what made it nice was that you still had a sense of being an outsider, so part of the thrill was that you were there with a lot of other outlaws even though people had the most mundane, stupid jobs you can imagine,” he said.

Boston’s queer community was generally much more integrated than the city of Boston itself, says Michael Bronski, professor of the practice in media and activism at Harvard University and a former reporter with publications like Fag Rag.

“I think that gay bars are probably the least segregated — not in terms of race, completely segregated, but in terms of class and age, the most integrated places that you could find. Because people were there to hang out with gay people … or meet somebody to have sex with, or meet a boyfriend or a lover or whatever,” Bronski said.

Outside of the bars, some queer people found themselves anywhere from the corner of Washington and Essex to Washington and Kneeland, an area called “The Combat Zone.” Now shut down and a part of Bay Village, it’s a neighborhood that the Boston Globe in 2018 called a “sleazy enclave of strip clubs, lounges, X-rated theaters, peep shows, and adult bookstores.” Kane says it was a place you never went alone.

While mostly an area for straight people due to a lack of gay bars, gay men were still frequent guests. They’d go to bathhouses, pornography bookstores and movie houses, the most famous of which was The Pilgrim Theater. Here, Mark Krone says gay people would gather and have sex.

“Gay men are sitting there having sex with each other in the seats while a giant screen is showing straight porn. After a while, they started showing gay porn in the ‘70s. There was no gay porn in Boston in the ‘60s — that started in the ‘70s,” Krone said.

Meeting other men in public places to have casual sexual encounters is known as “cruising.” Around this time, some popular spots to cruise were in The Back Bay Fens, at the Charles River Esplanade and in The Combat Zone.

Martha Vicinus, a professor emeritus at the University of Michigan and tour guide of “Boston’s LGBTQ Past,” says that cruising was particularly popular among sailors.

“They offered single rooms, hotels where you could rent by the hour or by the night,” said Vicinus. “And because there was a very large naval base … in Charlestown, there was a lot of cruising [from] sailors [who] knew where they could go for a pick-up.”

Gay nightlife was scattered throughout the city, but there was never a designated “gay neighborhood.” However, the South End had a sizeable gay population despite its dangerous reputation, said Kane, who bought a brownstone there with his partner in 1975 for $27,000.

“You only had gay couples who were buying houses and fixing them up because no straight people would go there with kids because that was just crazy. You couldn’t have a kid in the South End,” Kane said. “It was sort of like, ‘Yeah, you could do that because you were sort of a social pioneer.’”

According to Kane, from 1975 to 1980, the South End became akin to a hub for queer people. But gay people moving to the area came at the cost of gentrification.

“The gay boys were the ones who were gentrifying. They were absolutely gentrifying because they had money somewhere … and they wanted to find a place to live where you could be gay,” he said. “You could just walk down the street and be gay, and that was a new kind of thing. And the South End afforded that.”

Compared to the ‘70s, the ‘80s were a dark, sobering time, defined by death. On June 5, 1981, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released its first report of five mysterious cases of pneumonia in five gay men who lived in Los Angeles. Unbeknownst to the world, those were among the first cases of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or AIDS, an epidemic that would shake the queer community.

In Boston, the effects were palpable. Kane, who volunteered with the AIDS Action Committee, saw the devastation firsthand. Initially, he noticed a general awareness among the community, but nobody took it seriously until people started to die.

“A lot of people became more careful, more circumspect,” he recalled, though he didn’t participate in the hookup culture back then. “There was less of a kind of go out dancing and maybe hook up with somebody culture. There was that bit of caution or self-care — whatever you want to call it.”

Krone echoed Kane’s feelings, describing a mentality among gay men that made living with the disease isolating.

“It was a nightmare. And it’s hard to describe how bad it was because most people were not really out to their family, even if they led a very out life in Boston,” Krone said. “You didn’t discuss sex with your parents those days.”

Krone says many people — either sick or well — moved back home to their families. A plus side of the crisis was that it allowed the queer community to coalesce around a central cause — helping their peers.

“People were dying; people would be in front of their apartments because they couldn’t pay their rent,” Kane said. “At the beginning, of course, no one had any idea how it was transmitted … but once that was established, which was pretty soon, then there was just, how do you find support for these people? How do you provide hospice, basically for these people?”

What were once lively spaces and bars for queer people like Buddies and Sporters closed in 1985 and 1995, respectively. Other spaces like The Boston Eagle were put up for rent in 2021, Machine Nightclub and Ramrod closed amid the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, and disco club The 1270, named Boston Magazine’s Best Gay Disco in 1979, closed in 1988.

After a decade of trauma, death and loss, the next 20 years ushered in a new era that satisfied the need for physical queer spaces — the internet. With this new technology, hookup apps like Tinder and Grindr emerged, offering virtual spaces for people to meet in lieu of these physical entities.

K Anderson, who requested that his first name be omitted for privacy concerns, lives in London and hosts “Lost Spaces Podcast.” He discusses lost queer spaces and venues and their effect on the larger community in his show. He says the internet has forever changed how we meet people and view ourselves. But for him, these hookup apps aren’t as “organic” as a physical space can be.

“It’s quite disappointing,” said Anderson. “The value in having a gay bar that you go to every week is that you get to see people and build up an impression of them over time rather than having that like, ‘Oh, we’ve got this half-hour where we’re going for a coffee, and I’ve got to decide what the rest of my life is with you.’ And that’s just impossible to do.”