Addiction-related family support groups provides clarity during uncertain times

Through this process of sharing, family members are able to help one another navigate how to deal with and help their family members experiencing addiction while also taking care of themselves.

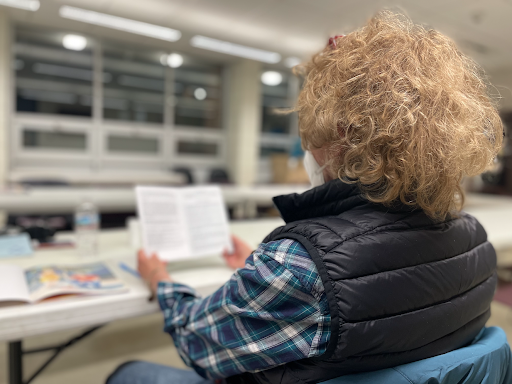

Donna Goneau has been attending weekly support group meetings for 21 years. She currently co-leads meetings on Wednesday nights in Cambridge through Nar-Anon Family Groups with co-leader Patricia Mederios.

“Nar-Anon helped me so much, personally, being able to love my son and cope with his disease and still live my life and not worry so much,” said Goneau. “It teaches you how to be honest and how not to fear constantly.”

Boston city’s numbers of opioid-related overdoses continue to rise annually. As more attention gets drawn to the city’s ongoing challenge regarding the opioid crisis with the intersection of Massachusetts Avenue and Melnea Cass Boulevard — also known as Mass and Cass — clarity needs to be found in order to solve the issue. The city has become a reflection of how addiction can impact and take over anyone’s life.

When Mederios discovered her daughter was dealing with addiction, she primarily started going to meetings to figure out where she went wrong as a parent. As time passed and she met other family members and loved ones of those experiencing addiction at the group, she had a realization.

“It wasn’t my fault. It was something that she chose to do,” she said.

The concept of support groups was not introduced into society until the 1930s, when the first self-help group, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), was founded. Since then, support groups have expanded their practices to a variety of individuals – including those experiencing addiction and people with disabilities, to parents and family members as well.

Although Boston has a number of support groups that family members can attend virtually online and in person, many people do not come. Goneau explained that one reason behind this is the stigma around addiction.

“You’re so worried about what other people think,” Goneau said. “A lot of mothers and fathers feel like they failed their children or otherwise they wouldn’t be in this mess.”

Eileen Ruhl, program director of Learn to Cope, said that when she first discovered her child’s struggles with addiction, “My gut told me something was going wrong, but you don’t want to believe it.”

Denial, shame and guilt are all common challenges family members’ experience that hold many of them back from attending support group meetings and allowing themselves the opportunity to understand and learn more. Ruhl said that although most people come to her meetings to get help for their family members who experience addiction, what they are really doing is getting help for themselves.

Once people start attending regular meetings, they realize “it’s a safe place for people to share and know they’re not alone,” Ruhl said.

At Learn to Cope, Ruhl explained, “We don’t tell people what to do at our meetings. We give suggestions. This is what I did… this is how I handled this…”

She said that, most importantly, “everyone’s story is different, yet it’s the same.”

Through this process of sharing, family members are able to help one another navigate how to deal with and help their family members with addiction while also taking care of themselves.

Elsa Vivant, a researcher who specializes in urban studies, has been investigating the opioid crisis in Massachusetts since 2018. After attending a number of support group meetings at different Boston organizations, Vivant found that the support groups are not just places for emotional support and sharing stories. They have also expanded their services to areas such as financial support, education and advocacy.

For example, medical insurance typically only covers the costs of rehabilitation centers. When people with addiction come out of them, their journey to recovery and normal life is not complete. Often many need sober living homes and other resources that are not paid for by insurance. Unless they have savings from their own jobs, they turn to family and loved ones.

Currently, there are nonprofit organizations that also support groups and offer funding for sober living and better quality treatment facilities, such as Shatterproof and Team Sharing. Some organizations also fund funerals for people who have lost a family member who had an addiction and cannot afford to hold a service themselves.

Learn to Cope provides members with free access and training in naloxone nasal sprays, commonly sold under the brand name Narcan. They also hold webinars and bring guest speakers to group meetings that come from all backgrounds of addiction, such as people who have recovered, doctors and people in the legal field.

Making support groups more inclusive and diverse is another goal many organizations have taken into consideration. Learn to Cope offers Spanish-speaking-only meetings, as many minority groups whose first language is not English lack the same opportunities for support. The Sun Will Rise Foundation holds men-only meetings, as men can find it difficult to talk about their vulnerabilities and emotional struggles.

As the coronavirus pandemic hit the country, Ruhl said in a lot of ways going online has provided people the opportunity to feel more comfortable to join support group meetings.

“People don’t even have to put their picture on. We don’t force anyone to talk,” Ruhl said.“You could just sit. They’re still getting something.”

Coming to meetings has helped a number of people. Ruhl, Goneau and Medierios are all examples of parents who had addiction affect their household, and through finding the support in group meetings and having it help their journeys, they have tried to provide that for other people.

Medeiros described her healing process with support groups as helping her realize that, “There’s hope and peace for yourself.”

“And there’s hope and peace for that person who is [experiencing substance use disorder], if they want to,” Medeiros said “Because I say it’s their journey, not yours. You have your own journey to heal.”