The quiet effort to change Massachusetts’ education policy

Parent groups are challenging Newton and Wellesley Public Schools for implementing social safe spaces and antiracism education in the classrooms

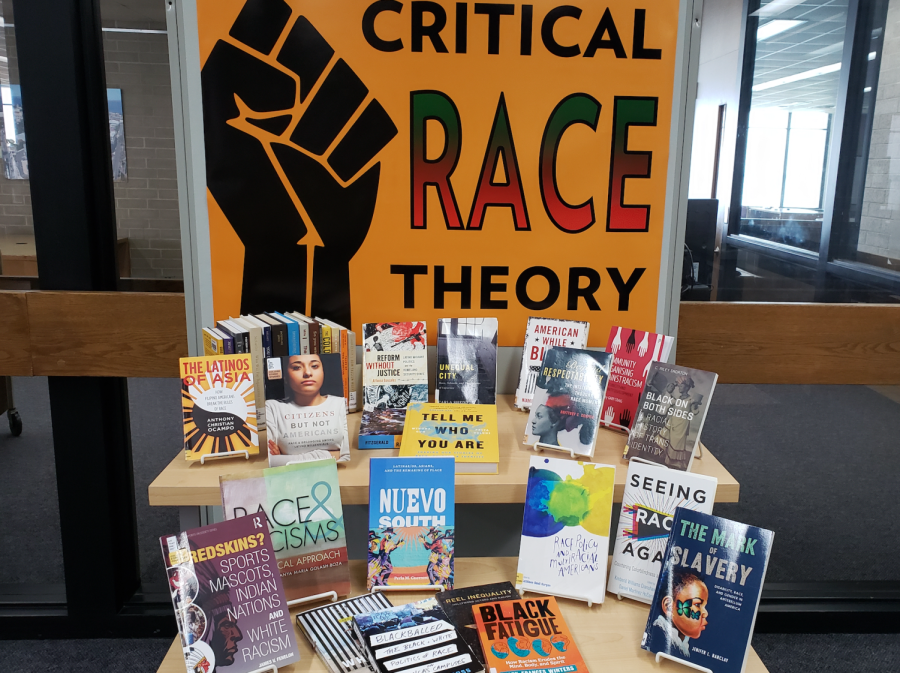

Even Boston’s most liberal suburbs are not immune to right-wing activism aimed at limiting how public schools can address social inequality. Both Newton and Wellesley have recently become targets of a conservative group that’s helping fuel vitriolic protests at school board meetings across the country.

Parents Defending Education group is suing Wellesley Public Schools over the district’s creation of optional discussion groups where students and faculty can discuss race. Newton, meanwhile, has been flagged by the group because of a PowerPoint presentation that pledged a commitment to antiracism at an elementary school.

“[Newton Public Schools] is committed to working tirelessly to ensure that we propel our community forward into an antiracist future,” reads the commitment. Parents Defending Education takes issue with this statement.

In this year’s elections, parental control over children’s public education content emerged as a polarizing issue nationwide. Mask mandates, vaccination requirements and education about race divided parents. School board meetings in states like Virginia and New Jersey became confrontational and hostile affairs. Parents Defending Education, which advocates against “indoctrination” in public schools, is one of the driving forces of these protests. Parent members monitor schools for education about race and equity, among other ideas, that they deem too political or “harmful.” The group has also filed civil complaints against school boards in New York and Ohio.

In Massachusetts, parents are approaching education policy subtly and strategically. During the 2020-2021 school year, Wellesley Public Schools introduced racial affinity groups, which were meant to provide safe spaces for discussion about discrimination and the experiences of individuals with shared racial identities. The groups were available to students and teachers and encouraged open conversation about race.

In response, five parents, represented by Parents Defending Education, sued the district’s superintendent, two principals and the district’s director of diversity, equity and inclusion. The organization accused a “disregard for students’ First Amendment rights” and said racial affinity groups do “far more harm than good.”

“Wellesley maintains that the important work the District has done around diversity, equity and inclusion is not discriminatory,” said Seth Barnett, one of the attorneys representing the school district.

The case, which is pending in the District Court for the District of Massachusetts Eastern Division, uses the defense of freedom of expression to back up students and families who expressed support for Blue Lives Matter and similar ideas.

“Students have the right to learn in an environment free from racist hate, including ugly slurs and hate symbols,” responded the Wellesley Public School attorneys in the memorandum in opposition to the initial motion. “The irony is not lost on defendants that plaintiff challenges protocols and curriculum designed to promote and support diversity, equity and inclusion by citing Brown v. Board of Education… and quoting the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.”

Wellesley is not the only Boston suburb targeted by the group. In neighboring Newton, Parents Defending Education flagged multiple “incidents” on an “IndoctriNation Map,” used to track any teachings or policies that parents take issue with. Anyone can file an “incident report” against schools or administrations. The organization has four parent chapters in Massachusetts and has flagged 22 “incidents,” and the numbers are rising. The far-right group allows visitors of the website to attach tags like “equity,” “anti-racism” and “promoting activism” to the “incidents.” A parent has labeled the “safe spaces” offered at a Newton middle school as an “incident.”

At Angier Elementary School, a parent alerted the organization’s network of the school’s 2021-2022 commitment to antiracism. “We are actively seeking to dismantle systems rooted in racism and replace them with systems and structures that lead to more equitable outcomes for ALL students,” read the pledge.

The parent who had raised the issue did not appear to have directly addressed this with the administration, as the Newton School Committee was not aware of the issue. Chair of the Newton School Committee Ruth Goldman did not realize that the group was active in Newton.

“There was someone requesting a lot of background information on our antiracist statements on our website and under the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion webpage,” said Goldman. “But we have not had a group of parents, for example, come to public comment.”

The education curriculum of Massachusetts is centralized. The state sets the curriculum framework, and the superintendents design their districts’ curriculums, intentionally leaving parents, the public and school committees out of the decision-making process. Goldman speculates that the lack of parental control embedded in state law makes parents less actively involved in public comments at school committee meetings than parents in some other states.

While parents aren’t regularly voicing complaints, Goldman says, some may back administrators who defer to phrases like “excellence in education,” which she refers to as a kind of “coded language.” While not overtly hostile, the use of this phrase indicates that test scores and district rankings should be prioritized over equity education. In this year’s election, Newton had four candidates running for the school committee focused on “excellence.”

“They never said ‘we don’t care about equity,’” said Goldman. “But they were more silent on it.”

The strategic movement to prevent educating students about racism is subtly building. Other conservative parent groups have pushed back against teaching about race. In Norwell, the conservative group No Left Turn flagged the reading lists of the district’s public schools, claiming that the students were “too young” to be introduced to issues like racism.

The pushback on education about race has been largely between parents and administrators. Newton Teachers Association president Michael Zilles said that politically, education was a “lightning rod issue,” but right now, teachers are more focused on students than policy.

“The burnout amongst teachers is really high. People have their heads down and are trying to get through,” said Zilles. He explained that students back in the classroom for the first time in over a year are experiencing behavioral challenges.

In school committee meetings, public comment is geared more towards incidents of racism than complaints about the content of education. In an October 12 meeting, educator and parent Christina Horner commented on a racially charged bullying incident that had happened on Discord over the summer, during which a group of Wellesley High School students used racial slurs.

Horner argued that it was time for “some real, honest dialogue regarding race” within the schools. However, it is exactly this kind of conversation that is being met with some contention.

According to Zilles and Goldman, parents who don’t support antiracist education are a very small minority. In general, parents and administrators agree that educating about race can help prevent ignorant, racist incidents in schools like the one on Discord.

Deed McCollum, another Wellesley parent, addressed the same racist incident. “If the schools in our community are not taking action and consistently trying to send the message that hate speech… and actions will not be tolerated, we will continue to perpetuate harm,” she said.