A Boston artist’s critical solutions to the housing crisis

Photo: courtesy of Pat Falco

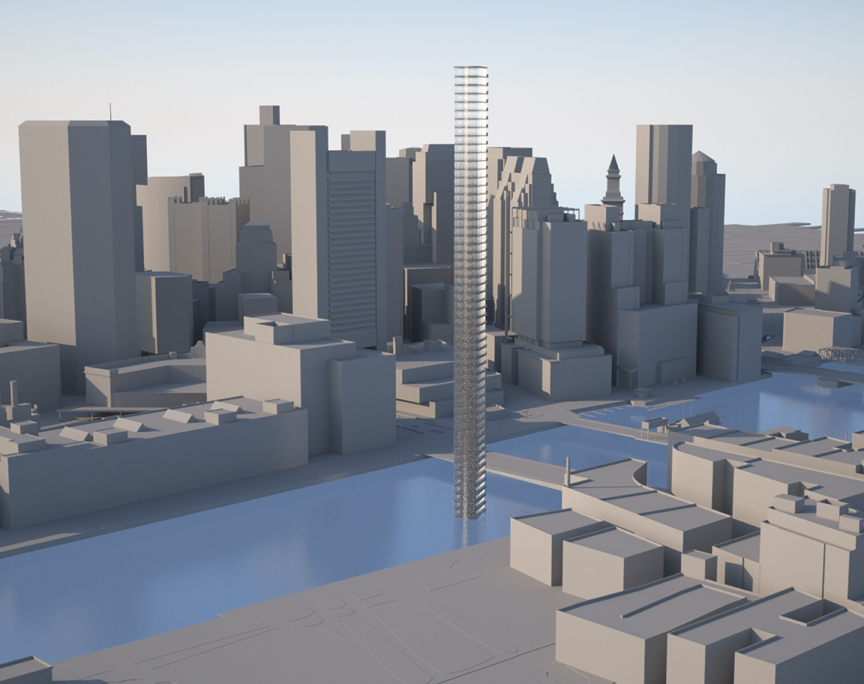

A photograph of Boston artist Pat Falco’s innovative housing solution design in Seaport

Art is generally seen as an aesthetic, decorative medium rather than what it can be: thoughtful, creative problem-solving. The city of Boston struggles with affordable housing, transportation and racial equity, as artists ponder the same issues. Boston’s Artists In Residence (AIR) program employs five local artists on a year-long tenure to work with city departments on projects that have to do with social issues and local policies.

Some of the key initiatives of the program are “to learn from artists’ expertise and practice, and think about how we can better our city policies, processes, and initiatives, to engage communities and residents that we’re not reaching, and to break silos in the city, connecting artists and city employees working on the same issues to work together,” Sharon Amuguni, the Program Manager for Boston AIR said.

“Artists will receive an artist stipend that covers their time and their work, and then there’s up to $10,000 in material funding available, so that’s supposed to cover expenses for artmaking related to your project or hiring other artists,” Amuguni explained. This money is separate from the stipend and is for any other materials or contracting work.

“There have been a wide variety of artists’ projects in the past four years, but a lot of them focus on social justice, addressing community needs. They focus on engaging the community members and bringing Bostonians into the City space,” Amuguni said, citing projects by Victor Yang, Erin Genia, and Karen Young, whose projects ranged from a youth-led campaign for school wellness blocks to an elder voice and visibility project utilizing Japanese taiko drumming.

One of the artists, Pat Falco, a Massachusetts College of Art and Design (MassArt) graduate, has focused on Boston’s housing crisis as the topic of many of his recent projects. He has produced a series of installations intended to critique housing policies and developments in Boston through a faux-luxury development company called “Upward Living Associates Inc.”

A previous project, “Luxury Waters,” seemed to propose a massive, 62-story glass condo building protruding from the middle of Boston’s Fort Point Channel in the highly-affluent Seaport district. The fake proposal, which confused passersby as truth, was actually an intricate, interactive satirical piece on gentrification and racial and fiscal inequality in Boston, especially in the Seaport area. The tower would consist of three-deckers stacked on top of each other, stretching into the sky. The three-decker is a three-story apartment building, usually constructed with light, wood frames. Each floor usually houses a single apartment, with whole buildings frequently being occupied by extended families on multiple floors.

for a 62-story luxury triple-decker rising from the Fort Point Channel waters in Boston’s Innovation District.” (Photo: courtesy of Pat Falco)

“I have personal memories of a three-decker, you know, and like I have a personal connection to it, and I think it’s just kind of an iconic Boston thing that represents home to a lot of different people,” Falco said.

The three-decker is a symbol that Pat Falco has used in several of his projects, including his more recent 2019 project, “Mock.” “I had been making a lot of work kind of centered around housing in Boston up to that point, but this was basically looking at the history of the three-decker there, and it’s elimination essentially in Boston as middle-income housing,” explained Falco.

In his study of the three-decker and workforce housing, he highlights the contrast in the Seaport area, which has seen the development of more high-end housing instead of more necessary workforce housing.

His installation, “Mock,” with the Now & There Public Art Accelerator program, involved a full-scale mock-up, an architectural device that allows designers to review the materials before constructing a project. In the highly-concentrated developments of the Seaport district, mock-ups are common for large-scale developments that represent the wealth and power that only a small percentage of the population are included in. However, this small mock-up of a three-decker seeks to remind people of a more diverse, inclusive and affordable Boston.

“Anti-immigration and racist backlash grew at the turn of the 1900s, and wealthy housing reformers worked to ban the construction of three-deckers and advocated for public housing as an alternative to house the poor. Part of a legacy of racist and anti-poor housing policy, the consequences of these actions helped build the framework of Boston’s current housing crisis,” explained Falco on his project page.

During his time as an Artist-in-Residence, he worked with the Mayor’s Housing Innovation Lab design fellow, Wandy Pascoal, who had been working on a project called the “Future Decker,”

The project focused on “imagining contemporary three-deckers and what they might look like,” Falco said. “It was a solution to the affordability crisis, so I helped support the work she was already doing on that.”

He said that the project saw them meeting with developers and including neighborhoods and non-academic architects in decisions to shape their neighborhoods.

“I think a lot of art talks about gentrification in a really shallow way, and I think artists generally tend to be really complicit in gentrification and displacement. So what had gotten me into this was trying to get past that and generally understand why stuff is happening and how it’s happening,” Falco said, explaining why he has chosen housing as his focus issue.

Falco has been making artwork about housing in Boston for almost 10 years. This led to him becoming more interested in policy in a way that connected to art.

Despite a strange COVID-19-driven virtual tenure as an AIR, Falco spoke on the positives of his experience.

“It was kind of a nice fluid residency. I ended up doing a few different things, but nothing in the way of a solid public art you could kind of look at,” Falco said, “It was a very fluid thing. I think the initial idea of the residency being centered around a single project, with a very visible outcome, just kind of evolved.”

“The department I was in was really small, and they’re meant to be experimental, and they were super amazing and super insightful. I was kind of surprised with how they were pretty radical and had ideas that I was excited to see already in the government,” Falco said about the Housing Innovation Lab team.

The five Artists-in-Residence also held meetings twice a month. Falco felt that the transition to working online was tough but found a collaborative community in his cohorts.

“I think it’s also important to realize that artists are community members, and they bring in a very specific lens as people who live in the city, and who use city services, and so part of the hope of the program is that you know nothing is going to happen in one day, but we’re in a culture that is acknowledging expertise and the value that the arts bring to the city, we can begin to find creative solutions to these problems together,” Amuguni explained.

Amuguni praised the AIR team, “I’m really thankful for the eagerness and generosity of both our artists and our city partners who, even though the year began with so much confusion, they were all so dedicated and decided we’re still going to participate, and we’re still gonna really bring our hearts into this work.”

Brooke Stewart, a post-graduate teaching fellow for art design at Northeastern University and practicing artist in Boston since 2018, applies for the AIR program every year. “It’s definitely competitive, but if you’re in the city long enough and you keep working, it’s just a matter of time before you get it, I think,” Stewart said.

In addition to being a practicing artist, Stewart teaches several art classes at Northeastern University, teaches a spin class and works at a restaurant as a waitress to afford to live in Boston. A significant portion of her curriculum involves educating students about contemporary and local artists.

“I think it’s really important for students especially to understand what’s going on around them, especially if they’re young and interesting. And if these artists live down the street from you, like, why not? They’re tangible and pretty responsive if you reach out,” Stewart said, “They’re not untouchable. Their work is cool, and sometimes that’ll be in major exhibitions, but they’re just normal people.”

Stewart also said that the city can do a better job with planning.

“I think maybe they throw an artist in at the table, but I don’t think they actually care,” Stewart said as she compared the inclusion of creatives with other performative diversity actions. She hopes for more agency and freedom as well as funding being afforded to these city artists.

Stewart’s first solo show was at the Distillery Gallery, which Pat Falco helps run, remembering his kindness and helpfulness in setting up her first show. Stewart said that Falco’s work is impactful for incorporating things he finds on the street and passersby to show the importance and meaning in everyday objects. “I think the best thing about Pat is that he embodies what it means to be from here. He’s the most Boston person I know,” Stewart said.

Both artists commented on the struggles of being a working artist in Boston and affording materials and studio space.

“Boston’s a hard city to be an artist in. There’s a lot of walls up that can be hard to get into, and it turns a lot of people away,” Falco said. “I think making art, making sure you’re excited about it and you’re not worried about necessarily where it’s going or the outcome — that’ll tend to come from you enjoying it rather than trying to force it into something.”