MFA union strikers use art exhibition highlighting past activist movements in fight for wage increase, improved benefits

“We’re just trying to bring attention to the issues that we’re advocating for and trying to get a fair and equitable contract.”

Artist Helina Metaferia aimed to highlight the history of activist groups in Boston for her latest exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA). Now that history is proving to be even more relevant, current employees at the MFA are copying her art as posters as they walk the picket line in a fight for their rights.

Metaferia, 38, is a professor at Brown University and a self-described “interdisciplinary artist.” She works across visual and digital mediums to tell stories about the human body and its relationship with identity and experience. Her latest exhibition, “Generations,” opened to the public on Nov. 6 and will be available until April 3, 2022.

“Generations” is intended to give perspective on the experience and history of oppressed individuals, including people of color, feminists, labor unions and queer activists. Metaferia felt inspired by movements in Boston in the 1960s to 1980s and wanted to demonstrate how individuals today have since learned from and built on the work these communities have done.

“I’m really interested in how history informs our present moment, so trying to understand why things are the way they are,” she said. “That curiosity takes me to understanding more about the past, and for me, the resources we have at our disposal is how people document the past. I’ve been focused on where women sit within history, how labor and service, and the labor of activists particularly, is documented.”

“Generations” consists of many different works, including mixed-media collages, a 17-minute long film with female descendants of civil rights figures and a participatory installation titled “The Woke.”

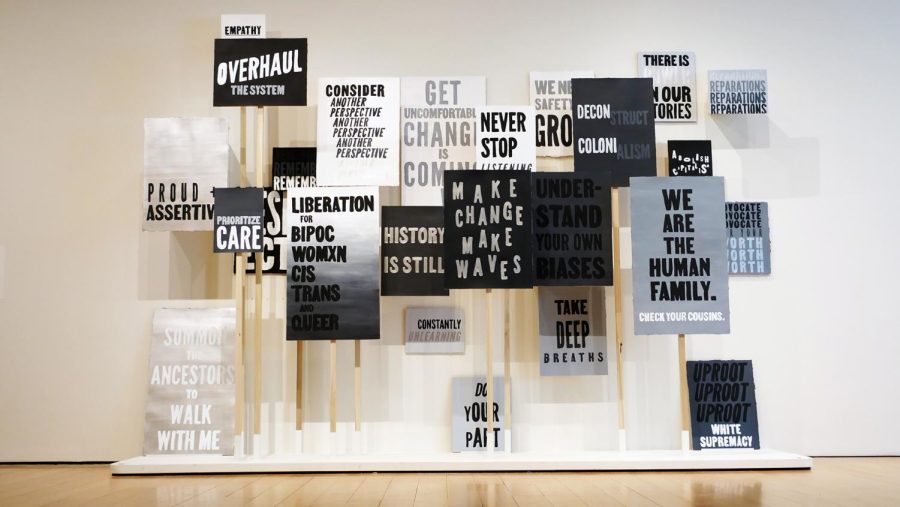

To create “The Woke,” Metaferia asked viewers of her previous works the question: What spurs your everyday revolution? Metaferia turned responses into a wall of picket signs, with typography commonly used in civil rights protests of the 1960s.

Copies of these signs included language like “Overhaul the system” and “Get uncomfortable. Change is coming!” and were used at the Museum of Fine Arts’ labor union protests held on Nov. 17, when some protesters carried copies of her posters on picket lines outside the museum.

Eva Mayberger is one of nine bargaining members of the union and has directly negotiated with management to represent the interests of the union’s membership. She explained that workers at the museum are fighting for higher wages and improved benefits in worker contracts.

“The very insultingly low proposal on compensation was a factor that really contributed to this vote, but really we’re just trying to bring attention to the issues that we’re advocating for and trying to get a fair and equitable contract,” Mayberger said.

The MFA Union, which represents about 200 workers, voted overwhelmingly to hold the one-day strike after seven months of contract negotiations with museum management. The union claims that their wages have been frozen for two years and that the museum refuses to guarantee any increases until 2024. While the museum remained open on the day of the strike, a crowd of workers picketed outside the museum from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.

The use of Metaferia’s work in these protests proves the relevance and importance of her message in the modern day.

“We feel really privileged that [Metaferia is] willing to support the MFA staff while her own work is currently being displayed in our galleries,” Mayberger said.

MFA curator Michelle Fisher, 39, worked closely with Metaferia on the installation of the exhibition. Metaferia is a traveling fellow with the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts and met Fisher over two years ago when Fisher was looking for a traveling fellow to feature in the museum. Fisher immediately connected with Metaferia as they bonded over their passions and their relationships with their mothers, both of whom had recently died. Metaferia’s artistic style impressed Fisher, and she immediately knew she wanted to display it at the museum.

“I did a number of studio visits with different artists, and what I loved about [Metaferia’s] work came from our studio visit together. It was really about hearing about her approach to practice, Fisher said. “I’m very interested in communities and in thinking about transparency and activism myself, and I do that in a number of ways in my curatorial practice.”

Prior to participating in the union strike, Fisher shared on Instagram how grateful she was for Metaferia’s support.

“I’m so delighted to have worked with the brilliant artist Helina Metaferia who reflects histories and current movements of protests in her show ‘Generations,’ up right now at the MFA Boston,” she wrote. “As she said, her work is not symbolic. It’s real. I will be printing out a version of one of [Metaferia’s] signs currently on display at the museum to hold proudly during the strike picket line.”

Metaferia had different approaches to crafting other parts of the exhibition, but all her works included interviewing and championing historically underrepresented individuals in art, most notably women of color, and using their stories to tell a greater narrative.

When making the “Headdress Series,” Metaferia led a workshop with the MFA in March for students, staff and faculty who identify as female and with the Black, Indigenous and People of Color, or BIPOC, community from local colleges and universities. In this workshop, the group discussed the connections between performance art and protest. Using three portraits of participants from that workshop, Metaferia created collages to put on their heads in the form of headdresses. These collages featured activist archival imagery and news clips from the libraries of Harvard University and Northeastern University.

The headdresses used in the work were a tribute to Metaferia’s Ethiopian heritage. Metaferia tailored each headdress to include archival work unique to the individual subject highlighted. Even in the age of the internet, Metaferia prefers to use library print archives in her pieces.

Working as a research assistant for Metaferia, Marla McLeod, 40, helped her research the archival documentation necessary for the exhibition. McLeod was impressed by how structured and organized activism was in Boston specifically.

“It was really digging into the history of Boston, the activism, the stasis in which activism existed within Boston,” she said. “To go in and to be able to look into all that detail and to really really be able to understand the hows and the why she chose specific imagery within the work is so cool.”

In addition to her help on the project, McLeod is one of the models featured in the series. McLeod loved seeing how Metaferia used their conversations with each other and pieces of her own identity to include in the final collage.

“I know that looking at the other imagery, and knowing how she built my own, it’s almost like insider information in a way because you get to see the way that she thinks about the individual. Because I have conversations with her and then I see how she includes pieces of me in that work,” McLeod said.

Maria Servellón, 31, is another model in the headdress series, a first-generation Salvadorian American artist and filmmaker. Servellón attended Metaferia’s workshop but did not expect to be called back to be featured in the exhibition. As she posed for her portrait, she thought of her grandmother.

“One of the things they told me before I got to the MFA was to imagine bringing a maternal ancestor with me and then think about her while being photographed,” she said. “Not being very familiar with my grandmother, I tried to call on her, this mysterious figure for strength, for knowledge, for power, for acceptance, for healing.”

Seeing the final product for the first time, Servellón was shocked by the size and detail of the eight-foot-tall portrait. The archival imagery in the headdress included elements that were distinctive to her background, including news clips from feminist movements, Salvadoran flowers and depictions of labor unions to reflect her work as a professor. However, what stood out to Servellón the most was a sign in front of the portraits advising viewers to “Approach the art with respect, do not touch.”

“I think that, even if it’s something small like that, is empowering and almost makes me feel really good about myself. I don’t think a lot of women of color are approached with a lot of respect often, being, what I feel like, at the societal bottom of the rung with respect and safety and health. This helps combat that in a way,” Servellón said.

Ja’Hari Ortega, 23, recently graduated from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and met Metaferia when she visited one of her classes. Ortega also participated in the March workshop and is featured in the exhibition. Ortega admired the individual stories Metaferia told with each portrait.

“I did feel drawn and connected to the imagery itself, like what it looks like as a whole. Looking at all three of them together, you can feel that they’re very different stories and very different people, and each headdress and each collage I feel like represents that,” she said.

In addition to the collages, Ortega was impressed by “The Call,” a film combining storytelling and song featuring four female descendants from civil rights figures Dick Gregory, Frederick Douglass, and James Baldwin. These women highlight how the maternal figures in their lives helped support the idea of “revolutionary everyday activism.”

“I loved the video. I watched it a few times. I think that oral history, storytelling [and] multi-generational conversations are so important. Watching that video [and] listening to them sing and talk was very comforting and very powerful,” she said.

Metaferia will continue displaying art that touches upon similar themes next year in Praise Shadows Gallery in Brookline. While this work will be different from the pieces featured in “Generations,” the message and approach to creating the work will remain the same. Founder and CEO Yng-Ru Chen is looking forward to working with Metaferia to amplify traditionally underrepresented voices.

“I think [Metaferia] is speaking to a lot of issues that are relevant to women and artists and people of color,” Chen said. “I opened my gallery in December of 2020 with a mission to work on highlighting artists that I feel like are exciting and that are speaking to our current culture and societies, but in some ways may have been underrepresented in the art market. I felt like she fit that theme because she is bringing to the forefront voices that have historically not really been heard.”

Chen explained how the use of Metaferia’s work in the MFA Union strikes proves that her message is a timely one that will remain prevalent for years to come.

“Her work now being really activated in that way is important because it should never function as just an object in a gallery space. It’s not precious in that way. It should feed our minds and motivate us and compel us to take action,” Chen said.

In her work, Metaferia wants those who view it to understand that the struggles of the past should not remain in the past.

“We’re still fighting a lot of the same struggles that are happening in Boston in the 60s and 70s; I’m sure we all feel remnants of that,” she said.

Metaferia’s main goal in making and sharing her work is to be remembered and make an impact. With MFA activists utilizing her art in their own fights for liberation, her art is doing just that.

“I always want to leave an imprint,” she said. “I’m really interested in memory and how long people talk about something and remember it. I think I’m obsessed with documentation because I’m really obsessed with memory and remaining in people’s consciousness … But really, what I’m hoping is when people walk away, they think about [“Generations”] in their day.”