With disparities between city and university COVID-19 testing, should colleges provide testing for local communities?

“We should be using these testing centers to help the community to reduce the spread of COVID-19,” said Michael Siegel, a graduate program professor at Boston University School of Public Health. “It’s really only a matter of time before it spreads into the communities.”

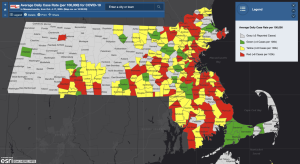

In recent weeks, the city of Boston has rolled back school reopening plans because of an increase in COVID-19 cases. In the city’s biggest neighborhood, Dorchester, the weekly positive test rate for the week ending in Nov. 2 is up to 11.9%, according to the Boston Public Health Commission. However, there are pockets of communities in the city that remain fairly unaffected from the general rising cases, including college students at Northeastern.

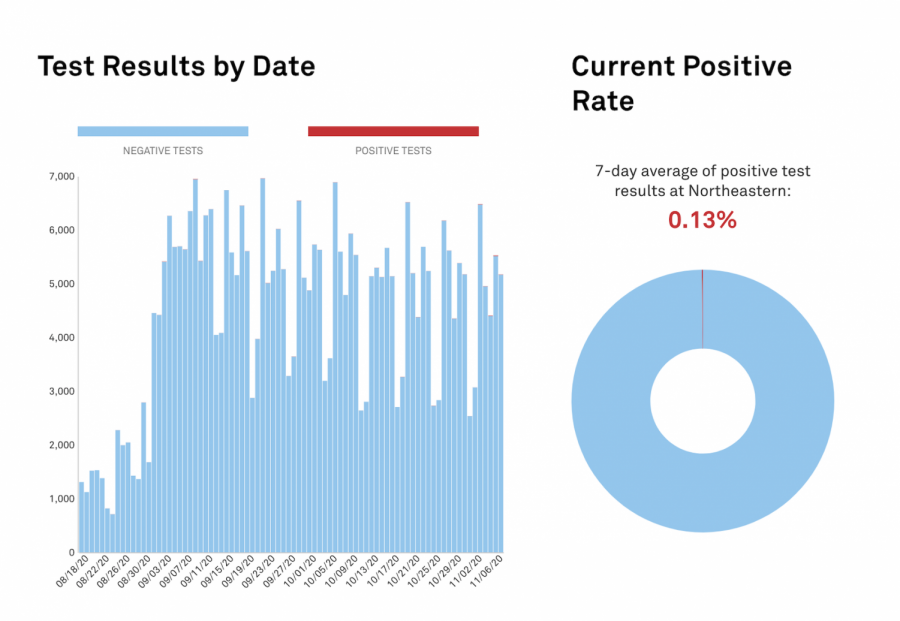

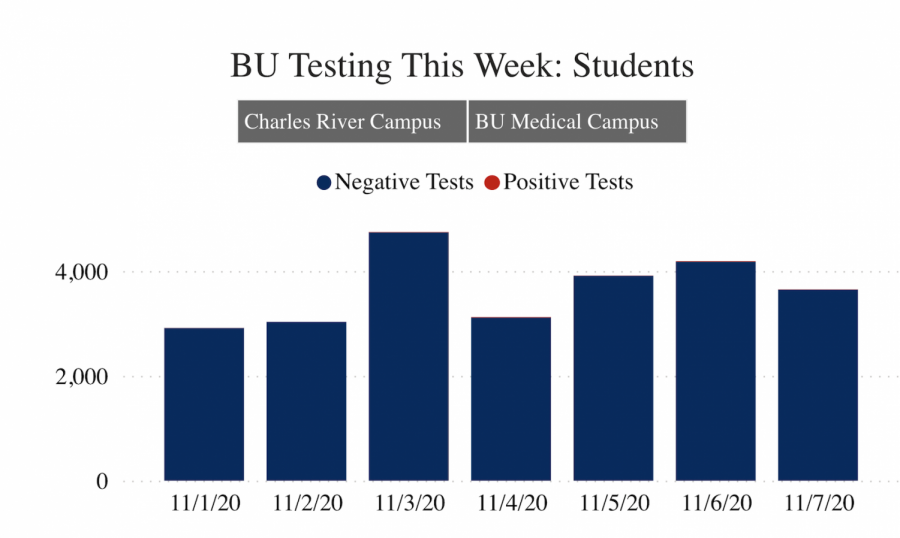

At Northeastern University, the current seven-day average positive test rate is 0.13% according to their COVID-19 dashboard, while at Boston University, the positive test rate for students the first week of November was 0.14%, according to their dashboard.

At universities in Boston such as Northeastern University, Boston University and Tufts University, the estimated turnaround for COVID-19 test results is approximately 24 hours. However, students are reportedly receiving test results even faster, usually in 10 to 12 hours.

To maintain a low positive rate, these universities and other colleges in Boston offer frequent testing with quick results for students, faculty and staff. Northeastern, for example, has said it can administer up to 5,000 tests per day. Northeastern requires individuals who primarily attend in-person classes to be tested every three days, according to the school’s website.

The rapid turnaround for results is possible because many universities built their own laboratories to process COVID-19 tests, and have partnered with the Broad Institute of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University, which currently supports more than 100 colleges in the New England and New York region.

As a result, university testing centers have the capacity to collect a large number of test samples per day at a low-price rate. This allows universities like Northeastern to collect up to 5,000 samples a day, while on the other hand, the city of Boston’s full current testing capacity is around 2,000 tests a day, according to Boston Mayor Martin Walsh.

The disparity in the positive test rate and testing capacity between the city and the universities poses a question of whether universities should provide free access to testing for the surrounding communities.

Universities have come under heavy scrutiny from their faculty and the Boston community for not providing public access to testing and aid to the neighboring communities despite having spent millions of dollars on robust testing centers. Even though students on campus have been contributing to the increase in COVID-19 cases in Boston, the testing centers and laboratories created by universities to process rapid results have not yet provided testing support to surrounding communities.

“We should be using these testing centers to help the community to reduce the spread of COVID-19,” said Michael Siegel, a graduate program professor at Boston University School of Public Health. “It’s really only a matter of time before it spreads into the communities.”

The only university in the metropolitan Boston area that currently holds a public-private partnership with local communities to provide COVID-19 resources is Tufts University. On Oct. 13, the school announced it would offer free COVID-19 testing for residents who are 18 years or older, living on select streets close to the Medford/Sommerville campus, on Tuesdays and Wednesdays from 3 p.m. to 6 p.m. This program will be available until Dec. 11.

Other than that, free testing centers for Boston residents are available through “Stop the Spread,” a state government initiative that aims to provide tests to communities that have a large number of COVID-19 cases. However, these testing centers tend to have a much slower turnaround for results. Brookside Community Health Center, which offers testing only on Wednesday and Thursday, takes 24 to 48 hours to return results. At Tufts Medical Center, results take two to three days.

“The city has done a lot to make free COVID-19 testing available across every part of Boston, in alliance with our community health centers,” said Kenzie Bok, the Boston city councilor for District 8. “But as the public health situation evolves, we may at some point need to also lean on the impressive testing capacity that our higher education institutions have built up to help our wider neighborhoods.”

Universities in the area have discussed providing access to the local communities but have said they must get through the legal challenges and safety requirements of opening the testing center to the public.

“I think it’s something that we’ve talked about at the university and continue to talk about. I mean, there’s a lot of nuance on how to make that happen, legally and safely,” said Jared Auclair, associate dean for Professional Programs and lead of the Life Sciences Testing Center, Northeastern University’s COVID-19 testing center. “Part of the university’s mission is to help the community it’s in, so I think that’s definitely the goal.”

Another issue is that if universities expand testing for the general public they would need more staff and resources to maintain the same turnaround time for results.

“There’s a lot of things that need to happen right,” Auclair said. “You need to have the extra capacity, you need to have trained staff, you need to have ways to collect samples and get them so that they’re accurate or observed.”

The decision by some Boston area universities to reopen campuses and bring students back was heavily criticized over the summer by residents and some city officials. When Tufts University announced its reopening plan in June, they were met with protests by local residents of Medford and Somerville, as well as city councilors and mayors. Siegel, the Boston University professor, called the decision racist and discriminatory, as it directly impacted communities of color and disproportionately.

In a letter to the Boston University School of Public Health, Siegel highlighted two main problems. The first was that there was an active dissent from local communities and that they had not consented for students to return to Boston. The second was the amount of resources and money that universities were spending on creating and operating their testing centers.

“In the School of Public Health, there’s a lot of talk about concerns about the community. But when it really comes down to it, our attitude was, ‘forget about the community,’” Siegel said.

In August, Councilor Bok addressed a letter to Boston University and Northeastern University, and urged them to not bring students back to campus to prevent an increase in COVID-19 cases.

“Your institutional plans for off-campus student communities are concerningly weaker; the seniors and other vulnerable populations who live in these neighborhoods must not be put at such elevated risk,” Bok wrote.