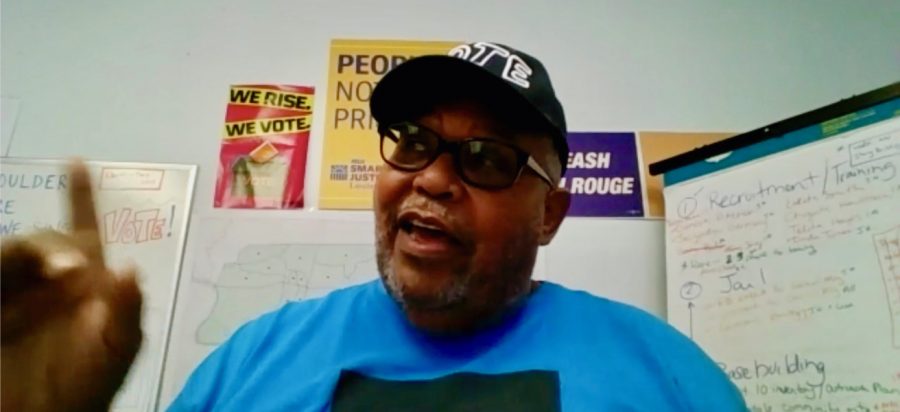

After 20 years in prison, voting rights activist Checo Yancy encourages you to register to vote

As voters started to cast ballots for the November election, incarcerated felons in many states including Massachusetts have to stay quiet. They lose their voting rights until they are automatically restored upon release.

Many previously incarcerated individuals never regain the rights. But in Louisiana, Checo Yancy, a 74-year-old formerly incarcerated person has been working to change that. He spent 20 years in prison and regained his voting rights last year after 37 years. He is now a director of Voice of the Experienced (VOTE), a grassroots organization that advocates for the rights of formerly incarcerated people.

Each state has its own policies regarding voting rights of those who are serving felony sentences, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. While some states deprive those rights until release or completion of sentences, other states never put such restrictions.

Activists in Massachusetts have been fighting to end the state’s felony disenfranchisement, which was introduced in 2000. “It is a form of voter suppression,” said Kristina Mensik, assistant director of an advocacy organization Common Cause Massachusetts.

“A lot of people are really confused about their voting rights and believe that they lose the right to vote,” said Mensik. Those include formerly incarcerated felons and people who are serving a misdemeanor. “Felony disenfranchisement, in effect, suppresses participation from those folks who maintain the right to vote,” she added.

Nationally, some states such as Florida and Kentucky have loosened the restrictions on felons’ voting rights in recent years. Louisiana is one of them as the state enacted a new law last year.

Before that, in addition to those who are currently in prison for felony charges, people were prohibited to vote even after release. Thanks to the new law, now, Louisianians who’ve been on parole or probation can vote, as long as they have no issues for five years.

Mensik welcomes those changes in other states. “I think Louisiana helps. Even though it’s a different set of circumstances, but helps propel our work here to move the needle forward.”

“There is a recognition that’s a part of this national movement, that restrictions on voting rights don’t have a place in a modern and true democracy,” she added.

Checo Yancy, a formerly incarcerated turned activist fighting for the right to vote of formerly incarcerated people, shares his life story and what it means to have voting rights back. Tune in to his powerful voice. You can also find a transcript of the podcast below.

Transcript

Reporter: In Louisiana, convicted felons did not have voting rights until they completed their sentences. This changed last year, when the state enacted a new law. Now those who’ve been on parole for more than five years can vote. Checo Yancy, 74, is a formerly incarcerated person who regained his voting rights last year.

Yancy: My name is Checo Yancy. I spent 20 years in prison. 7,309 days.

Reporter: In 1983, he was convicted of felony charges and sentenced to life in prison. He was put in Louisiana’s Angola prison and released on parole in 2003.

Yancy: I did something 37 years ago that I’m responsible for. I had a victim. And I’m very sorry for that.

When I got to prison, I realized I had put myself there. And I needed to do everything I could do to do the right thing to earn my way out of prison.

Reporter: Yancy is now a director of the grassroots organization, Voice of the Experienced. He is one of the founding members.

Yancy: We actually started this organization inside of Angola almost 40 years ago, and we wanted to get our family members and everybody involved in understanding that voting and election was an important part, we wanted to change the law within like prison. We discovered that voting is the way that you do that.

Reporter: Now, Yancy educates formerly incarcerated people about the new law and encourages everyone to register to vote.

Yancy: We’re doing lip dropping right now. Making literature and going into the doors and put it on people’s door knob so they can get an idea of what Know Your Vote is, what candidates are on the ballot.

If you’ve been on probation or parole, you’ve been out five years, you have the right to vote, and I’ve heard people say, “Huh? I can vote here? What do I need to do?,” then we have to sit out there and explain to that person.

Before the pandemic, we were taking people to the registrar’s office. And it wasn’t about who you gonna vote for. It was about getting you registered.

Reporter: Last year, for the first time in 37 years, Yancy was able to cast a vote in Louisiana’s state election.

Yancy: It felt so good last year during the governor’s election. Advertising came in the mail that had my name on it, asking me for my vote. That means I’m a registered voter. I have a say-so.

I vote because my vote is my power. My vote is my voice. When I vote, I’m voting for my children. I’m voting for my granddaughter. I vote because my voice matters.

Reporter: Yancy has two children. Family is a big part of his life.

Yancy: My son is in his 40s and my daughter is in her 40s. They were young when I went to prison. One point they hated me. Because of what I did to the family.

But now, you know, they see their father working for justice working for this. You know, my son told me other days, he sent me something he said, I’m trying to get people registered like my father. And it made me feel good. It made me really feel good that I was doing something that my son was proud of. My daughter sends me a text every day and says, “Daddy, I love you.” That is important.

This election is probably the most important election in the history of my life. Because we have an opportunity to change what’s going on in America right now.

My motto is “I will beat you to the polls.” Are you gonna let a former incarcerated who’s been in prison beat you to the polls? You should be ashamed of yourself.

Reporter: This is Yuriko Schumacher reporting.