Massachusetts community-based healthcare project works to increase COVID-19 testing access

The commonwealth’s focus on community health in the state-wide coronavirus testing initiative has created a model that experts believe is crucial to making further advances in ensuring a widely accessible public healthcare.

In July, the state pioneered Stop the Spread, a strategic program that provides free coronavirus testing for all Massachusetts residents, whether they’re symptomatic or not, at 75 testing centers located in the hardest-hit areas, including Chelsea, Everett and Randolph. This effort was built through partnerships between the state and laboratories like the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute and Technology and Harvard University, as well as hospitals across the state. The hospitals and testing centers have coordinated staff and volunteers to help facilitate testing and preventative care for COVID-19.

“The benefit is sharing the responsibility,” said Monica Lowell, vice president of the Community Benefits Program at University of Massachusetts Memorial Health Care, the largest health care system in central Massachusetts. “The hospitals, we can’t do it alone. By coming together, we are all working towards the same goal, trying to control the spread, and so I would say this is the best thing, because what it means is that everybody is contributing to take care of this horrible situation.”

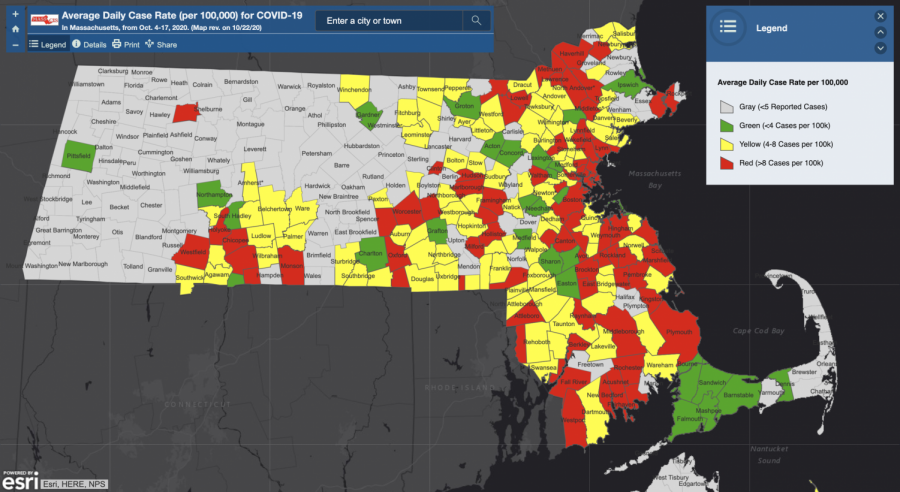

Testing centers are primarily located in what are designated as “red” communities on the commonwealth’s COVID-19 Community-Level Data Map. These are higher risk communities that have an average of more than eight cases per day, per 100,000 residents, such as towns like Brockton, Framingham, Springfield and Lawrence. However, testing is not limited to the residents of those communities.

University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center in Worcester, is one of many hospitals providing free testing on behalf of Stop the Spread. Worcester is a designated “red” community with 6,846 total cases and an average of 12.1 cases per day, per 100,000 residents, as of Oct. 22. The hospital administers on average 400 tests a day. The system requires a massive effort, including finding the physical space, setting up tents and computers, registering patients, collecting demographic information and informing patients about their results.

“It’s boots on the ground on all levels to make this happen,” Lowell said. She emphasized how they are “capitalizing on the prevention end” in their outreach.

“We do tool kits, which is a bag that has masks, cloth masks, sanitizers, it has information on COVID, what to do if COVID [is] an issue in their household, proper masking and the instructions on how to get the results for the COVID test,” Lowell said. She said they also provide their coronavirus infographics in different languages, using translations by Harvard Medical School. The focus is on languages that are spoken widely in Worcester, such as Spanish, Vietnamese and Portuguese.

Testing alone involves a lot of moving parts, but laboratories like the Broad Institute are responsible for processing those tests. The partnership between the Department of Public Health and the Broad Institute was initiated by the state because the research institute could operate at a scale beyond their own. Stacey Gabriel, senior director of the Genomics Platform at the Broad Institute in Cambridge, which rapidly transformed into a COVID-19 testing facility, spoke about how they work with medical centers to facilitate their testing programs.

“It absolutely takes a village,” said Gabriel, who is also a scientist at the Broad Institute. “We’re happy to do our part of it. We don’t do all of it, but it’s been gratifying, the part that we’re doing in the middle, anyway.”

The “part in the middle” involves processing 70,000 tests a day, with a maximum capacity of 100,000 tests a day, and returning results within 24 hours, on average. The Broad Institute generally charges between $35 and $50 for processing tests, but Gabriel said they currently charge the state $25 for each test, which she said is the bare minimum required to cover their costs.

Gabriel said that there is no fixed timeline for when they will stop testing, and they will continue to test as long as there is a demand for it.

Offering free testing is an example of how community based health care can reduce barriers to access. It considers the financial factor that may otherwise prevent an individual from seeking care. According to Leland Ackerson, associate professor in the Department of Public Health at University of Massachusetts Lowell, income is an example of a “social determinant” that may limit access to health care.

“Whether a person seeks health care or not, in this case, seeks testing for COVID-19, is patterned by those social determinants,” said Ackerson, who holds a doctorate in social epidemiology. “The more you can attend to those, the better. If you make it so accessible in their neighborhood that they can access it, if you can consider the cost, it sounds terrific.”

Other examples of social determinants include gender, education and transportation.

“A person can get sick because they can’t see the doctor if they don’t have transportation, so suddenly, transportation and the MBTA becomes a public health issue,” Ackerson said.

Janet Mulligan is the executive director of nursing at Fenway Health, a community health center that primarily serves the LGBTQIA+ community. She similarly spoke about the strong interdependence between social determinants and public access to health care.

“What we know is that if you don’t address the social determinants of health, it is very difficult to address physical health needs,” Mulligan said. “If someone has diabetes and hypertension, but they don’t have the right food to eat or a roof over their head, no matter what treatment we give them, it won’t stick, unless we address the social determinants of health.”

Fenway Health has long been an advocate for community health, practicing “meeting the people where they are, meeting the people in the community they’re in, getting their health care needs met, whatever those may be,” as Mulligan said. The Stop the Spread initiative seems to consider some of those values in their endeavor for widely accessible testing.

Both Mulligan and Ackerson agreed that collaboration and interaction with communities and other relevant organizations is key to understanding how to best serve their patients. For example, Ackerson said, if a person gets sick by inhaling a trigger for their asthma, and the presence of that trigger has to do with where they live and what their income is, “housing becomes a public health issue [and] the housing authority becomes a public health organization.”

Ackerson further emphasized just how varied, persistent and generational some social determinants can be, and how “it’s really hard to completely eliminate them.” For instance, if an individual lives in poverty now, that determinant will only be exacerbated in the face of a public health crisis such as COVID-19, which makes preventative measures extremely significant.

“What I like about public health and why I’m in public health is because the premise of public health is prevention,” Ackerson said. “What distinguishes people in public health from health care is oftentimes [that] health care is reactionary. The point of public health is to try and prevent those things before they happen. Public health is preventative, it’s meant to be collaborative.”

Mulligan also expressed hope that similar partnerships that formed between clinicians and laboratories will emerge between clinicians and pharmaceuticals.

“The cost of drugs to treat these patients, to treat HIV, to cure [hepatitis] C, to treat diabetes,” Mulligan said. “Some of the god-awful price gouging for EpiPens and insulin, to me, that’s a public health emergency.”

Regarding the preparation and ability of the state to enforce such a widespread testing effort, Gabriel of the Broad Institute said that while the work has been commendable, it was not simple.

“A learning for the future is how do you make this more universal so it can be more adaptable and scalable,” Gabriel said. “It works, but it’s challenging. We couldn’t go and build this overnight.”

Being aware of the social determinants that could prevent access to health care can inform the direction in which public health must move to ensure widely accessible care to those who need it.

As Ackerson succinctly said, “Think proactively, not reactively.”