COVID-19 pandemic exposes Boston green space disparity issues

Physical activity and exposure to nature boost immunity and improves people’s mental health. But quality green space is scarce for many Boston residents.

For many Boston residents, the past six months have been spent tucked inside working or taking online classes. Although this long period of isolation can lead to mental health issues including depression, studies have shown that nature can help. For residents living in densely populated Boston neighborhoods, however, finding an accessible green space within walking distance can be difficult.

Physical activity boosts immunity and reduces inflammation, effectively lessening the severity of COVID-19 symptoms, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Being active is also linked to mental health benefits, like reducing anxiety and depression.

Humans are social creatures who thrive when we “feel” connected to other human beings and prolonged isolation similar to the one occurring now due to the pandemic can be harmful, said Desiree Dickerson, a clinical psychologist in Spain who specializes in academic mental health and well-being.

“It is a death sentence as far as our evolutionary wiring is concerned—back in the day if we were isolated we’d either be eaten or we’d starve,” Dickerson said. “We are wired for social connection and belonging. And when those needs aren’t met, we see increased psychological distress, anxiety and depression and a raft of other health issues.”

But physical activity requires open green space—a luxury that few Boston residents have available at their homes. Boston residents often live in multi-unit buildings and rarely have the space to exercise at home. With schools and other recreational facilities closed, green spaces have naturally become the go-to resources, but aren’t always accessible to everyone.

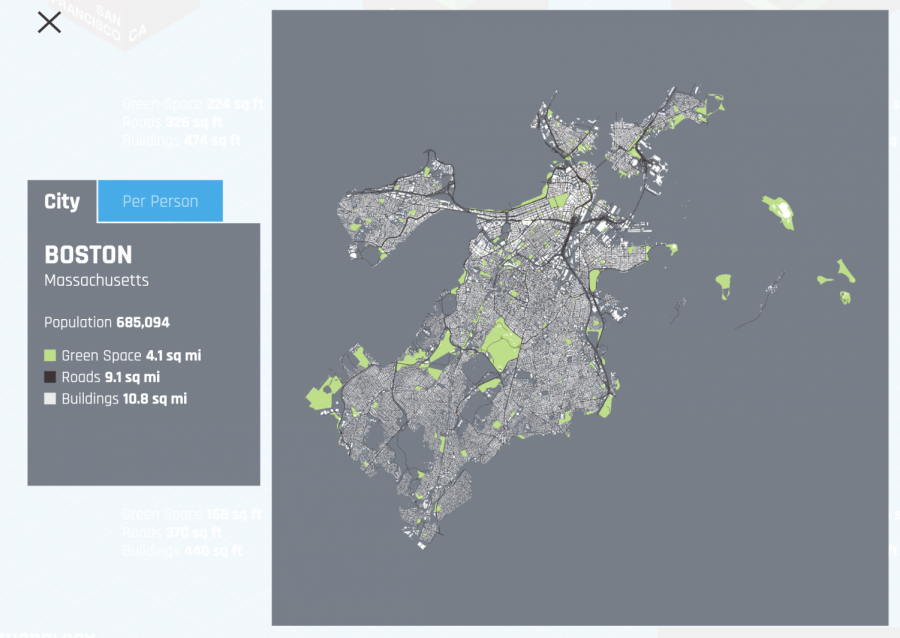

Boston green space per resident was ranked among the nation’s lowest in a 2019 report by telematics company Geotab and data shows that those green spaces are not distributed equally. The approximate green space, maintained by the city’s Parks and Recreation Department, per 1,000 people is around one acre in the South End and East Boston compared to six acres for residents in Back Bay-Beacon Hill. In Atlanta, the greenest major city ranked by Geotab, the green space per 1,000 residents is more than 20 acres.

“The whole question of whether Boston residents have the quality of access to parks is going to become increasingly fraught because more people will want to use the parks which are already heavily used, and there will be fewer resources to take care of them,” said Ted Landsmark, a distinguished professor and director of the Kitty and Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University.

Ease of access to green space is important but so is quality of experience

In 2018, Mayor Martin Walsh announced that Boston reached a major milestone in “ensuring park access for all residents.”

“Reaching this milestone is a big step for our city to ensure that every resident, no matter the neighborhood, has a high-quality park or open space within a 10-minute walk of home,” Walsh said in a press release.

But the issue is not so much about ease of access as it is about the quality of the experience. One such example is New York City’s Central Park, located in the heart of Manhattan.

“A majority of the people who are enjoying Central Park don’t live anywhere close to it,” Landsmark said. “Many of them have to travel more than an hour to get there and they do it anyway, because they know that when they get there the experience may not always be predictably the same, but they know that when they leave the park they will not be disappointed.”

But a well-maintained park means higher costs. And the fact that residents are flocking to parks due to restrictions in restaurants, bars and other venues of entertainment would mean more maintenance costs, which can exceed existing funds.

“As COVID and the post-COVID period makes it more likely that there won’t be as much money to take care of the parks, what should we protect? And how do we decide what to protect?” Landsmark said. “That’s going to be a really hard set of decisions for a lot of policy makers. It could be in three months, next spring or two years from now, but it is going to be a big, big question.”

“If you ask people, ‘Would you be willing to pay 200 dollars a year to fix the streets? Not so much in your neighborhood—you wouldn’t know that it was going into your neighborhood, but everywhere in the city.’ Most people would say, ‘Oh, but that is why my tax is paid for. I am already paying for that. I want the potholes fixed for free,’” Landsmark said. “Nothing is ever for free. Everything requires trade-offs.”

In the meantime, there are small things individuals can do to bring themselves closer to nature.

“There is plenty of evidence to suggest that exposure to nature is beneficial for our physical and mental health,” Dickerson said. “It improves mood, reduces anger and stress, and increases happiness.” But she said we don’t need acres of greenery for it to be effective. “There is even evidence for the benefits of a simple potted plant in your office and in hospital rooms.”