The North End shouldn’t work.

It breaks all the traditional rules of city planning. It’s very densely populated. There’s little to no green space. And for decades it could have been considered a slum.

Anyone who’s actually visited Boston’s North End, though, knows that it’s a vibrant, energetic and healthy neighborhood. A ten-minute walk can take pedestrians past a variety of thriving restaurants, bookstores and bakeries. People flock to the North End because they enjoy being there. Somehow, the North End defies the odds.

The North End isn’t the only seemingly impossible community like this. Urban neighborhoods that defy all the logic of city planning are everywhere, from New York’s Greenwich Village to The Mission in San Francisco. They’re crowded and they’re crisscrossed with twisty, hard-to-navigate streets. They started out as low-income slums and they have very few parks. But they’re also thriving cultural hubs with close-knit residential communities and relatively low levels of crime.

Many say the reason is diversity. Their residents are from a wide range of backgrounds and incomes, work in many different fields, and keep many different schedules. In part, demographics are natural and organic, but there is a lot that designers and developers can do to encourage diversity and build stronger neighborhoods.

DREAM Development LLC is a local minority-owned business that recently won the Boston Housing Innovation Lab’s Housing Innovation Competition. The competition, run by city officials, was aimed at creating innovative, affordable, compact housing that fit the Roxbury neighborhood.

DREAM Development’s design proposes mixing residents with a range of incomes and from multiple generations, and housing them in compact, affordable apartments on the city-owned lot.

“The overall objectives of the project — we wanted it to be easy to build, we wanted it to be sustainable, and we wanted it to fit into the context of the neighborhood,” said Gregory Minott, the managing principal of the 24 Westminster Avenue project.

The question that remains is can the diversity and successes that the North End has experienced naturally, be recreated elsewhere in Boston?

Diverse neighbors for diverse opportunities

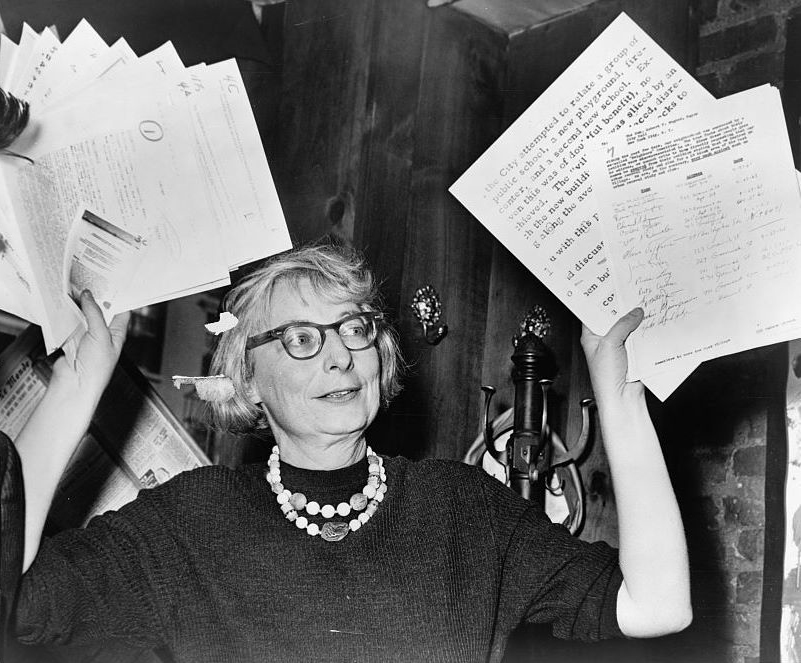

Jane Jacobs, an activist and journalist who lived in Greenwich Village in Manhattan in the 1960s, was one of the first to establish the theory that the key to healthy neighborhoods is diversity. Much like the North End, Greenwich Village at the time was a twisty, crowded neighborhood with a thriving cultural scene. It was also, by today’s standards, considered a slum, so valueless that it was almost bulldozed to make way for a highway.

Jacobs became a local hero leading the charge against demolition and was the first person to point out that unconventionally successful neighborhoods could provide a pattern for how to create a healthy neighborhood — a pattern that could be copied.

In her 1961 book, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” Jacobs argued that conventional urban planning had it backward. Cities didn’t need more parks or streets laid out in a grid. Rather, it needed social and economic diversity, diverse daily schedules and diverse interests and needs. When there are lots of types of people, lots of types of opportunities develop, she said. When there are diverse opportunities, residents can meet all their needs as they grow and change without having to move away.

In Boston’s North End, neighbors with a differing practical skills were able to work for trade when banks refused to issue loans in the area, turning tenements into comfortable family homes, and helping individuals to become invested in the neighborhood they built with their own hands.

At 24 Westminster Avenue, Minott is applying a lot of Jacobs’s theories about diversity to the development project, a building made up of 11 units, one-bedroom apartments with three-bedroom townhomes above. Each three-bedroom unit takes up two floors and are stacked directly on top of a one-bedroom unit: they can be sold separately or deeded together. The idea is that smaller families or single residents can purchase one space, while larger families can purchase both the one-bedroom and three-bedroom apartment and connect them. Families could even deed the spaces together and rent out one as a method of wealth generation.

“Adaptability was just key, you know,” said Minott. “As your needs change over time, as you need to contract your space or grow your space you have that flexibility, you have that ability for additional income if you rent the ground floor out and live on top, so we wanted to make it a wealth generator for families.”

Jacobs also stressed the importance of residents being able to stay in the same space as they grow older and their needs change. In 24 Westminster Avenue, units can be combined as a family grows and as parents age — one-bedroom units are cheaper and more accessible for people with limited mobility.

How to price for diversity?

But while mixed-income housing, the kind Jacobs envisioned and Minott is implementing, may improve neighborhoods overall, it often makes life worse for residents on the lowest end of the income bracket. Increasing the number of high-income residents in a low-income neighborhood leads to gentrification as the cost of living becomes too high for many of the original residents to continue to live there.

Henry Louis Taylor, Jr., a professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Buffalo in New York, said that if profit is the only motive, developers will create spaces for rich white people in order to make the most money.

“People prefer keeping any sizable amount of low-income housing in their neighborhood out, because of the impact that tends to have on the market values,” Taylor said.

Two of DREAM Development’s apartments are designed to be affordable for families who earn 80 to 100 percent of Roxbury’s median income — somewhere in the low $200,000 range — while the other ten will be priced at market rate in the $400,000 range.

“We’re definitely targeting the middle income buyer, because they’re the ones that really don’t get much subsidy,” Minott said.

In Roxbury, where the median income is $31,601, this means even the “affordable” units are out of financial reach for half of the neighborhood’s residents — something Taylor called a “joke.”

“One of the ways they get around inclusive zoning is by raising the limits,” he said. “That’s just way, way, way too high.”

Taylor said the way to combat pricing for profit is for the government to take some land out of the free market and set it aside for low income housing and businesses.

This is how other developments in Boston, like the Maria Sanchez House in Mission Hill, were created. Because the housing is subsidized it can cater to people with much lower incomes than DREAM Development can afford. The house, named after State Rep. Jeffrey Sanchez’s mother, is reserved for seniors making less than half of the area median income. Without a space like the Maria Sanchez House in the rapidly-gentrifying Mission Hill, many of those low-income seniors wouldn’t be able to afford to keep living there.

“The vision and the planning was, it essentially centered around how do you develop affordable housing and create opportunities for people who want to live in this neighborhood but maybe can’t afford to anymore,” said Collin Fedor, an advisor speaking on behalf of the Office of Rep. Sánchez.

Taking into consideration the needs of, and constraints on, the area’s most vulnerable residents — whether it be at the Maria Sanchez House, 24 Westminster Avenue, or the North End — seems keys to building resilient neighborhoods.

“To create, on any kind of mass scale, authentic and legitimate mixed income and diverse neighborhoods, you have to be able to change the way the housing market operates,” said Taylor. “It can be done, and it has to be done in my view, because that’s the only way to create just communities.”