The portrait of Diana, Wilson, and their daughter Sammy hangs in the apartment from which they were recently displaced in Eastie. / Photo by Jorge Caraballo Cordovez

By Jorge Caraballo Cordovez

East Boston (Eastie), Boston’s fourth largest neighborhood, is being rapidly transformed. Its location and public facilities have made it attractive for a wave of developers and investors. They’re buying and renovating properties to rent them to young professionals and students who can pay much more than the Latino working class community that has been living there for more than two decades.

The fear of being displaced can be felt all around the neighborhood. You hear it in casual conversations on the bus; you read it on the “room-for-rent” signs on the laundromat’s cork boards. It’s told by the families who just got an eviction notice as they walk around Eastie on Sundays to see if they’re lucky enough to find a unit with the old, affordable prices.

I’ve been reporting on displacement in East Boston since 2015, and I’ve seen how it has rapidly snowballed. One of the variables that contributes to Latinos’ displacement is lack of information: few of them know that getting an eviction notice doesn’t mean they actually have to leave, that they have tenants rights no matter their legal status in the country, and that there are NGOs and lawyers who could provide them free legal assistance. East Boston, Nuestra Casa seeks to make that information more accessible to the Latino community in Eastie.

What is this project about?

East Boston, Nuestra Casa is a series of postcards that I made in collaboration with a group of Latino families who are facing eviction. The goal is to inform other Latinos about the causes of the housing crisis and the available resources they have to remain in the neighborhood.

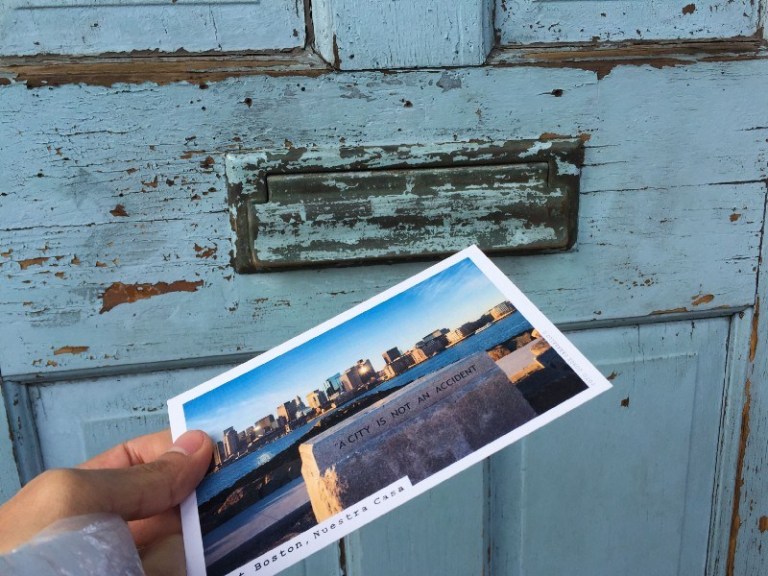

We chose this printed format because it guarantees us that every tenant will receive the information directly to their home. Besides that, East Boston, Nuestra Casa is a public Facebook page and a Facebook private group where more than 200 tenants are sharing their stories, questions, and concerns.

This is a hybrid project of journalism and activism: It seeks to mitigate the anxiety caused by the housing crisis with useful information for the affected community.

The first postcard is a panoramic of downtown Boston taken from Eastie. On stone is carved an ironic truth: “A city is not an accident.”

What’s on the back of the postcards?

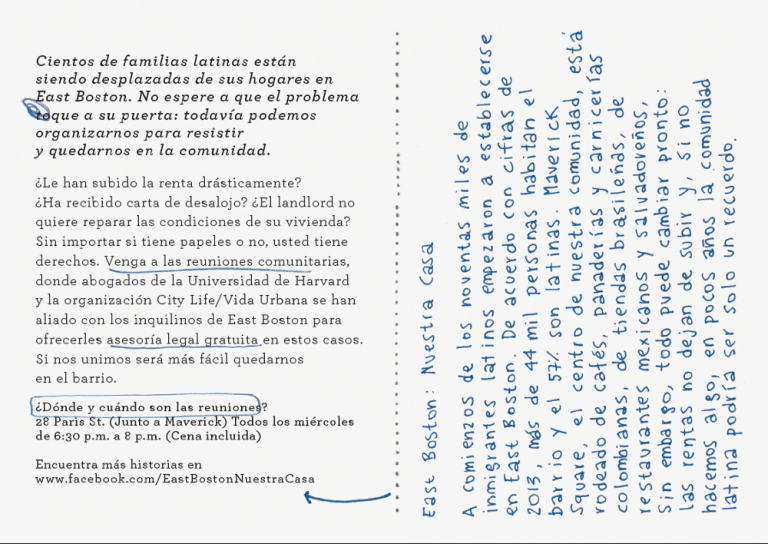

The back of each postcard is divided. The left side is the same on every card. It’s meant to hook readers by describing some of the most common causes of displacement: huge rent increase, eviction notices, negligent landlords. After getting your attention, you’ll find information about the community meetings where tenants can get free legal assistance. The message is brief and it calls for action:

“Hundreds of Latino families are being displaced from their homes in East Boston. Don’t wait until the problem knocks at your door: We can still organize ourselves and resist so we can stay in the community.

Has your rent skyrocketed? Have you received an eviction notice? Is your landlord reluctant to fix the unit where you live? It doesn’t matter if you’re an undocumented immigrant or if you have legal status: You have rights. Come to the community meetings where Harvard lawyers and the NGO City Life/ Vida Urbana have allied with Eastie’s tenants to offer free legal assistance.

Where and when are the meetings?

28 Paris St., Next to Maverick Square, Every Wednesday from 6:30 p.m. — 8:00 p.m. (Food is served)

Find more stories in www.facebook.com/EastBostonNuestraCasa“

The right section is different on each postcard. It’s handwritten and it combines both narrative and data to explain the dimensions of displacement. There are testimonies of Latinos who have been effectively evicted, and also of tenants who have won their cases in housing court. You can also find statistics about housing in Boston and read some policies that have been suggested to slow down displacement.

Each postcard is designed to be self-contained and work independently, but you can have a better picture of the housing crisis by reading all twelve of them.

How did all this get started?

I met most of the portrayed families thanks to the weekly community meetings facilitated by City Life / Vida Urbana, a nonprofit focused on housing and displacement. On average, 50 tenants — most of them Latinos — meet every Wednesday in the basement of an East Boston church to share updates about their cases, exchange support and helpful tips, discuss legal strategies with the lawyers and plan actions to raise awareness in other neighborhoods. It was in those meetings where I got to know the problems of the community and where I began thinking on how could I help them as a journalist.

There has been a constant concern during the community meetings: Thousands of Latinos in the neighborhood are ignorant of the resources available to help them fight their cases and try to stay in their homes. In response to that, I suggested creating an information campaign to reach those people and engage them with a discussion about displacement.

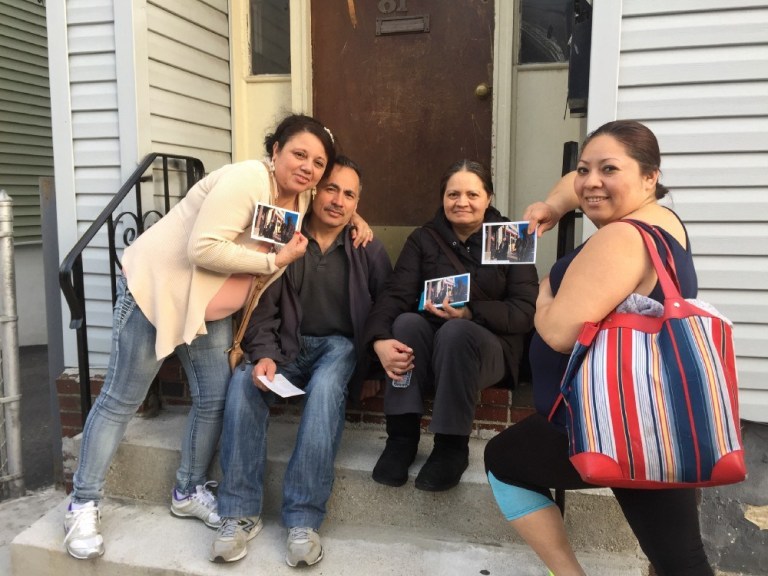

At the time, I was taking a photography class with artist and activist Lara Baladi at MIT, and her course helped me to come up with the postcards idea. I presented it to the community and they liked it. More than a dozen people — most of them women — raised their hands to volunteer. Even though many of them are undocumented, they were not discouraged with the idea of their portraits and testimonies circulating around the neighborhood. (However, to protect their privacy, we omitted their last names and, obviously, their addresses).

How did the community participate?

While taking the portraits in their apartments, the families told me about how the threat of displacement has affected their health, their jobs or the education of their children. But even though they’re facing a very difficult situation, the process of making this project together was a happy one. They invited me to their family parties (where they made me drink aguardiente, a strong Colombian liquor that I had avoided for two years). I was with them until late in the night when their kids were getting ready for bed. I watched them play cards for hours, and I spent afternoons in their homes where they fed me with treats from the delicious Salvadoran bakery.

After taking the photos, we wrote the stories. I collected data about the housing market in Boston, and also about Latin American community. I found, for example, that the value of the properties in Eastie has increased 36 percent in the last two years, and that Latinos are the demographic group that earns the least money in Boston and across the United States. We put together those numbers with their testimonies.

Finally, we were lucky to have the support of Laura Pérez, a talented Colombian designer who created the graphic identity of the project.

In one week ten volunteers have walked around the streets and put the postcards in the mailboxes that are marked with Latinos’ names (by law, we’re only allowed to put them in mailboxes that don’t belong to USPS). We’re also handing them to Latinos on the street, in laundromats, and at bus stops and subway stations. Their response has been surprising: people want to talk about this, they know it could happen to anyone at any point. And, yes, most of them didn’t know about the meetings.

How are you measuring the impact of the project?

You could measure the impact by comparing the lists of attendance to the community meetings before, during, and after distributing the postcards. If the strategy is successful, we expect to see more Latinos every Wednesday.

The second metric would be the number of followers and their engagement in the Facebook private group.

However, we think that this project is already having an impact on the community. The collaborative process of making the postcards and the way they’re being distributed is starting a conversation in the neighborhood. The housing crisis in Boston has been well reported by local outlets, but not in Spanish.

What’s your personal interest in doing this work?

I’m one of the approximately 20,000 Latinos who live in East Boston. I felt at home when I arrived to the neighborhood, but I was also aware that my privilege as an international student was problematic: I’m one of the many students or young professionals moving to Eastie and competing with the working class community for housing units. I’m part of the problem, but could I also work with the community to find possible solutions?

Have other reporters used postcards to tell their stories?

Yes. Photographers Anastasia Taylor-Lind (English/Swedish) and Mónica Gónzalez (Mexican), have done beautiful works using postcards as their medium. Do you know about someone else? We would love to hear about it.

You can see more photos and read the texts of all the postcards here.

You can read this article in Spanish here. A version of this story first appeared on Medium.