By Felippe Rodrigues

There’s something to be said about the state of women’s hockey in America today: it’s never been better.

Women now have their own paid professional league, the National Women’s Hockey League, or NWHL. After some controversy last March, USA Hockey finally succumbed to the demands of female players on the national team, increasing their compensation in a landmark deal. With less than a year to go before the 2018 Winter Olympics, Team USA’s women’s hockey team is the favorite for gold. The team clinched its fourth straight world champion title last March.

Yet, one undeniable truth remains. Be it on the ice rink, the soccer field, or the basketball court, the vast gender pay gap is still the rule in sports.

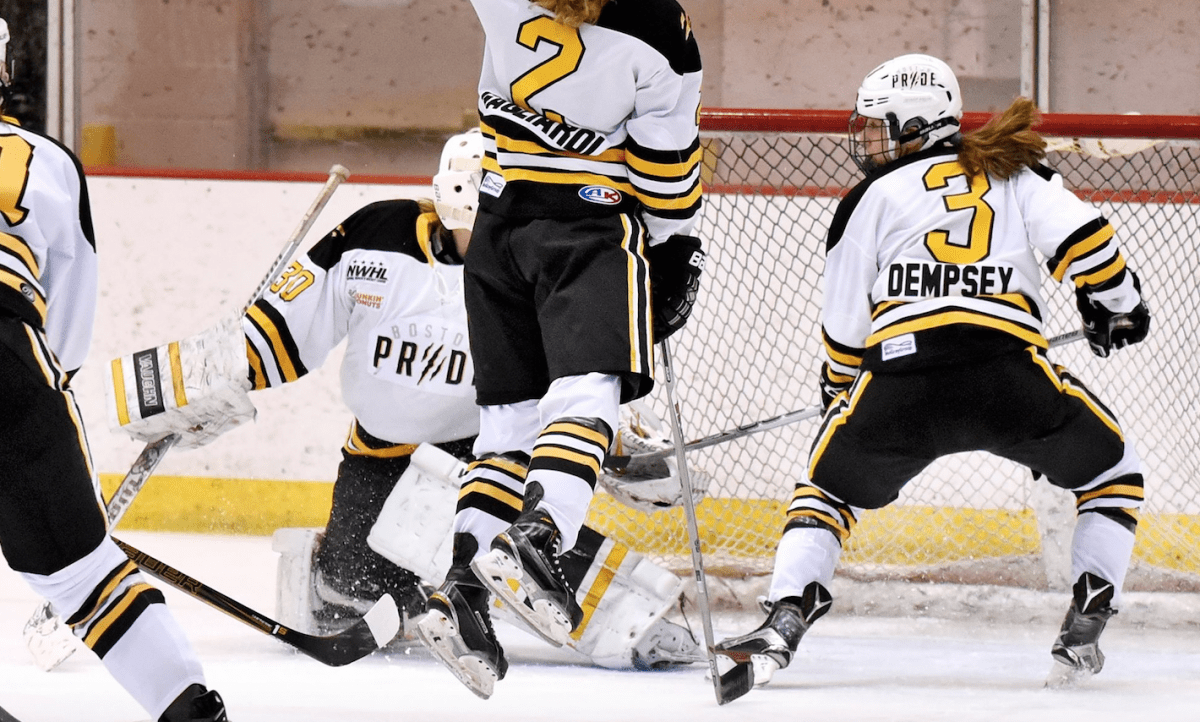

Take Jillian Dempsey, 26, a forward with the local NWHL franchise, the Boston Pride, as an example. She is a former college standout from Harvard, where she majored in Classics and became an All-Ivy League player. Dempsey was also nominated for the Patty Kazmaier Award, given every year to the top female player in the NCAA.

But, still, Dempsey can’t make a living as an athlete. Aside from being a professional hockey player, she also teaches fifth grade at the Cummings Elementary School in her hometown of Winthrop, Mass.

“Throughout my whole life, I have been balancing school and balancing hockey. Now, of course, it is a little bit tougher being an adult and having a full work day,” Dempsey said. She squeezes in gym and cardio sessions before going to work. At night, she heads to practice in Brighton. “[It is] definitely tiring at times. It is a long day, but I am doing what I love in my job and playing hockey. I can’t really complain.”

According to data released by the NWHL in 2015, Dempsey earned just over $10,000 from the league, a figure that already included a share in the sale of player jerseys.

The idea of playing hockey full-time brings a smile to Dempsey’s face. But there’s no such option for most women aspiring to play professional hockey today. Superstars in the NWHL may receive a maximum salary of $26,000 a season. But even starters at the last World Championship final—Hilary Knight, Kacey Bellamy, and Brianna Decker—do not get paid the maximum in Boston.

While the most reliable estimates put the gender wage gap at 20 cents nationwide, the gap widens significantly in hockey. The best women in the country, and arguably in the world, earn four cents on the dollar when compared to the minimum salaries paid at the National Hockey League, or NHL.

Despite income inequality in professional sports like hockey, there is a relentless optimism in women like Dempsey or Haley Moore, the Pride’s general manager and a former player herself.

“We are looking to pave the way here and continue to pay our players and find out what the best model is for everyone to just keep moving forward,” said Moore. “Our players have been tremendous [in] jumping on board and understanding their roles as pioneers for the sport.”

The NWHL faced a financial crisis last season, and commissioner Dani Rylan, also a former player, decided along with the league on a pay cut to players’ salaries to “keep the league financially viable.”

It may be a while before women in hockey enjoy a livable wage. Even the Women’s National Basketball Association, or WNBA, which is the only example of a women’s sports league that pays relatively high wages, sees All-Stars go abroad during pre-seasons to make money on the Chineseand Russian markets. It took the WNBA years to reach a sustainable model, and in those years, plenty of sacrifices were made by athletes in the name of the love for the game.

If that is what it is going to take, Dempsey could be the one that helps make it happen. She recently re-signed with the Pride for her third season in the NWHL.

“Jill is probably the player who loves hockey the most out of everyone that I know, honestly,” said Moore, who played with, played against, and coached Dempsey.

The fact that an athlete of Dempsey’s caliber cannot choose to dedicate herself to the sport she loves at a time when women’s hockey is at its best is simply disheartening. But it is also what fuels the dedication of this teacher and player, to prove people wrong day in and day out.

“It is kind of what we pictured growing up: having an equivalent of the NHL and being able to be paid to just do the game that you love,” Dempsey said. “It would be amazing if there were more financially viable options, but it is a work in progress and we are working towards that. The big thing for us is we get to play hockey.”