By Jasmine Wu

In 2015, Joyce Chen won the housing lottery. Out of nearly 4,500 applications, the Asian Community Development Corporation (ACDC) awarded 95 affordable housing units in Chinatown. Chen knew that she was getting a rare opportunity.

“There are not too many rooms for renting out. And there are more people that want to move in, but can’t because it’s expensive,” said Chen.

Chinatown is one of few Boston neighborhoods in which Chinese immigrants do not encounter cultural or language barriers, Chen said, adding that many only speak Chinese. But residents do face another obstacle: the exorbitant cost of rent.

While Chinatown has seen a dramatic increase in luxury condo development, there are far more limited options for affordable housing. Lotteries, like the one that Chen won, are often the only way low- and moderate-income residents can move into the neighborhood. The most recent housing lottery was for 51 affordable units; ACDC received 1,600 applications.

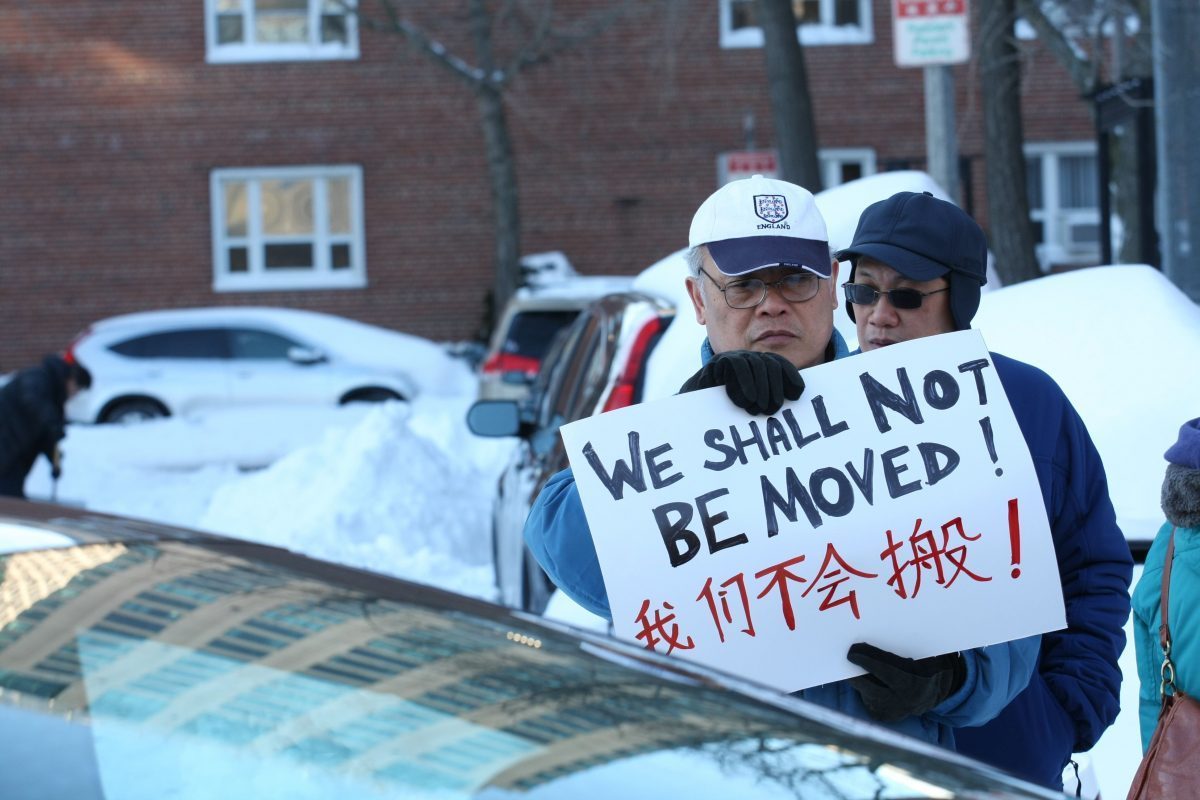

In addition the rising cost of living, long-time residents have been impacted by neglectful property owners. Arturo Gossage, treasurer for the Boston Chinatown Resident Association (CRA), has lived on Hudson Street in Chinatown for 11 years. He vividly remembers a time when the owners of the neighboring building neglected their property and, eventually, all of its residents had to leave.

“We saw the last family getting moved out of those buildings,” Gossage said. “I usually take a lot of photographs, and it was so powerful to see them getting moved out. But I think the image would’ve been so degrading.” Gossage said that, as residents watched the demolition outside, everything they owned was out on the street with them.

Once residents are forced out of their homes, they are unlikely to find other affordable options in their neighborhoods. A BostonInno report found that Chinatown’s median rent in 2015 was $3,381, the highest of any neighborhood in Boston.

“Chinatown won’t exist if things keep going the way they are going now,” Gossage said.

Change in Chinatown

Gentrification has become a factor of everyday life in Chinatown. But for a neighborhood located in the heart of downtown Boston, this burgeoning issue receives little coverage from major media organizations. And the stories that do cover this topic are frequently inadequate. Community newspapers are often the only outlets offering consistently in-depth coverage, and their readers are usually the very same people affected by the issues they cover. Without an increase in thoughtful coverage, one of Boston’s most celebrated neighborhoods may be doomed to a complete transformation without acknowledgement from the rest of the city.

“Chinatown is changing drastically,” said Chu Huang, co-chair of the CRA. “As gentrification hits, there is a deepening divide of socioeconomic inequality, and a misunderstanding and misconception of who actually lives in Chinatown today.”

According to a 2013 report by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, the overall white population in Boston decreased between 2000 and 2010, while the white population doubled in Chinatown. During this same period of time, the Asian population in Chinatown decreased and now makes up less than half of all residents. In 1990, Asians made up 70 percent of Chinatown’s population.

The report also highlighted the changes in median household income. For white residents of Chinatown, the median household income was $40,554 in 2000. In a five-year average between 2005-2009, that number rose to $84,355. Meanwhile, the median household income for Asian residents dropped from $16,820 to $13,057. During those same years, the poverty rate for Asians increased from 39 percent to 44 percent, the highest poverty rate for any racial group in Boston. As the report notes, “This juxtaposition in the increase of median household income for whites and a decrease for Asians is a classic indicator that working class Asian immigrants are and will be priced out of Chinatown.”

The rise of luxury developments, such as Millennium Place and The Kensington, has contributed to the wealth disparity in Chinatown.

“Recently, there have been so many high-rise buildings that do not benefit the Asian community, these luxury buildings. Asians need affordable housing,” said Hin Sang Yu, 80, co-chair of the CRA with Chu Huang. Yu, who lives in a four-bedroom apartment with his wife, daughter, son-in-law, son and daughter-in-law, spoke to The Scope in Cantonese using a translator. “The goal is to stabilize Chinatown, not gentrify it.”

Inconsistent coverage

Community leaders agree that, while gentrification is one of the biggest problems facing Asians who live in Boston, the problem is not widely recognized. A quantitative analysis of The Boston Globe’s stories show that in 2017, there were only six written about housing and Chinatown. In contrast, The Globe ran 11 stories between Dec. 3 and 7 about Patriots tight end Rob Gronkowski’s suspension and its aftermath.

But 2017 was a peak for coverage of housing in Chinatown in recent years. In the same analysis, The Scope found that only four stories were written on the issue in 2016, three in 2015, four in 2014 and three in 2013. The Scope contacted the archives of The Globe and confirmed these figures.

Boston’s two major public media outlets also have seemingly minimal coverage. Over the past five years, WGBH and WBUR have collectively published online around a dozen stories that discuss housing in Chinatown. This number reflects only those articles published online and not any that may have run on radio or television (and were not posted on the outlets’ respective websites).

Most of the articles published The Globe in 2017 were written by Katheleen Conti, a general assignment business reporter with a focus on real estate. In an interview over the phone, Conti said that she always tries to look for people who are “willing to share their stories, because [gentrification] is a deeply personal issue.” She believes “having the anecdotes, the people, makes the story human and better for the reader to understand.”

But Chu Huang, of the CRA, said she’s noticed that many stories from these mainstream outlets are told with a focus on business rather than through a human lens. Instead, she said, a story should make readers think, “‘I want to do something for this neighborhood because it’s for the people in the neighborhood. I didn’t know this neighborhood was experiencing this like mine is, too.’”

Despite these issues, there are examples of thorough reporting. Some past coverage by The Globe, WGBH and WBUR has highlighted communities at risk in Chinatown’s housing crisis.

In 2014, columnist for The Globe Yvonne Abraham focused on two low-income, long-time residentsand wrote: “Without them, Chinatown would be a characterless, Disneyfied version of itself, or, worse, an Asian West End. And Boston would be a smaller, colder place.” The following year, Maria Sacchetti, now a reporter for The Washington Post, wrote this article for The Globe that both humanized the issue and gave historical context. Phillip Martin at WGBH reported this thoughtful story in 2016, in which he toured the sites of shuttered apartment buildings and the condos of the wealthy with Leverett Wing, a community activist. Last year, WBUR reporter Simón Rios reported on housing advocates who are promoting affordable apartments in the neighborhood.

The problem is the infrequency of comprehensive articles like these. Placing those isolated examples in context, Chinatown’s housing issues receive thorough coverage from major outlets only a few times per year.

“It’s frustrating because we’re always left out of the conversation,” Wing said. “The news cycle moves quickly … but the problem has definitely not gone away.”

Local solutions

Ling-Mei Wong, editor of a Chinatown community newspaper named Sampan, said she does see coverage of Chinatown, but that it’s very general.

“If I see a Chinatown story in The Globe, I do clench my teeth, because it’s either about food or crime,” she said. In the past year, the newspaper has run 15 stories about restaurants in Chinatown, though six of these were routine “where to eat in Boston” pieces. “It’s great that food is mentioned and certainly local crime is an issue, but it makes it seem like that’s all that Chinatown is — a place to eat — when, actually, people live here.”

Sampan, New England’s only bilingual Chinese-English publication, is one of several news outlets in Boston that cover the Asian community. Others include The Epoch Times, which covers China and is distributed weekly in Boston, and World Journal Boston, a daily newspaper printed in Chinese and based in Chinatown, featuring local and national news. These publications cater to the Chinese community, which, according to a 2010 UMass Boston study, is the largest subgroup of Asians in Massachusetts.

“We’re smaller, hyperlocal and very narrowly focused on Chinatown. If there’s a new building, a new housing development, we’re there. We’ll always look at city-wide issues from the angle of Asian-Americans,” said Wong. “The Globe has a general readership of almost all of the New England region, but we as Sampan can be a small boat to move information from the larger media to our community in a format or language they understand.” Sampan, in Chinese, is a small wooden boat. When larger boats are unable to access shallow harbors, a sampan can be used to receive goods and transport them onto land.

Though regional newspapers may have greater reach and resources, smaller organizations seem critical for local issues of importance. Quincy City Councilor Nina Liang said that she tends to form relationships with the local newspapers and tells them about events more often, because the local publications are always present.

Marty Baron, the executive editor of The Washington Post and former editor of The Globe, has talked about the difference between local and hyperlocal coverage. In an interview on CBS News journalist Bob Schieffer’s podcast, “About the News,” Baron said The Post continues to devote considerable resources to local and regional coverage, but that it had to draw the line at anything more granular.

“It’s very difficult for a newspaper of The Post’s size, or even for major metropolitan newspapers, to do hyperlocal coverage,” Baron said. “Many of them have tried. … There have been very few successes.”

Earlier this year, however, WBUR may have created a model for hyperlocal coverage by major news organizations. In July 2017, to increase and improve coverage of Dorchester and Mattapan, WBUR partnered with The Dorchester Reporter. Along with cross-publishing neighborhood stories, The Reporter hosts at least one WBUR journalist in its newsroom. This collaboration allows both organizations to expand their audience and improve their coverage.

Another solution for the lack of consistent hyperlocal coverage is greater diversity in media. News organizations should focus attention on Asian representation in the newsroom, said Paul Watanabe, director of the Institute for Asian American Studies at UMass Boston.

“It makes a difference to have reporters who are from Asian-American communities,” he said. “There is a conception often among the leadership of news organizations that, while we need to respond to diversity to include large numbers of African-Americans and black people within the business, there’s not such a comparable need to include Asian-American personnel.” He added that it is often an issue of familiarity. “You don’t have people who are attuned to the community to the extent they could be from personal experience, background and sensitivity.”

Shirley Leung, a business columnist at The Globe, said that her background as an Asian-American does play a part in the stories she writes.

“You tend to write from your own experiences,” she said. “A lot of newsrooms struggle to cover diversity, and often it takes an editor or reporter to drive coverage. If you have someone who’s passionate about the topic, it’ll get covered.” Since stories about race are more often enterprise than breaking news, Leung said, reporters should keep an eye out for news events that will allow them to discuss the topic. “We just have to find our way into it,” she said.

In July 2017, Leung wrote about a poll conducted by The Globe on politics and race relations that left out Asian-Americans. The omission was a way to include voices such as Leverett Wing and Michelle Wu, a Boston City Councilor. It started a larger conversation about Asian-Americans in the media, the rise of Asians in politics, and their role in elections by citing a civil rights group poll that filled The Globe’s void and surveyed Asian-Americans’ thoughts on the same issue.

“What the results tell me is that Asian-Americans have a lot to say. … Pollsters and the media can no longer just view race through the prism of white, black, and Hispanic,” Leung wrote. “If we want race relations to improve in this city and elsewhere, we have to bring everyone along.”

Leung is right. There is no reason for the media to exclude what is, according to a recent UMass Boston study, the fastest growing ethnic population in Boston. These Bostonians are being priced out of their own homes, and their stories are often left untold. There is a crucial need for hyperlocal news outlets. But without a swift effort to improve coverage and increase diversity in bigger newsrooms, Asians will continue to be silently displaced from Chinatown without spotlight and without action.