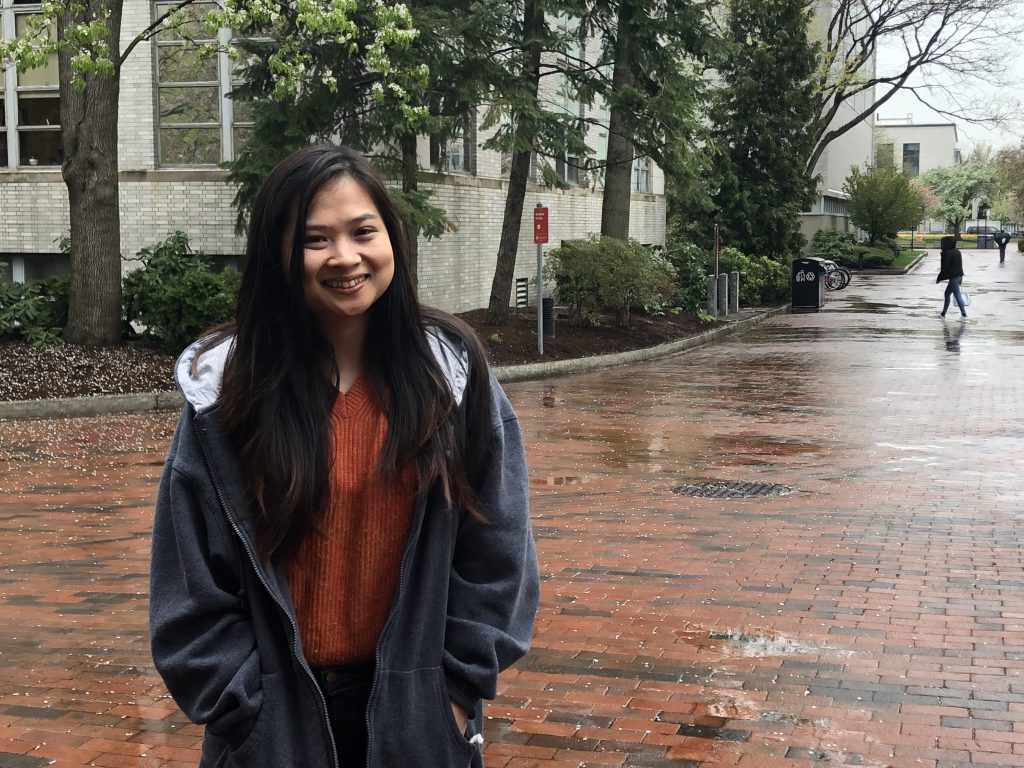

Photo by Eileen O’Grady

By Yuuki Nishida

Harvard University sophomore Robert Jomar Malate finds it difficult to identify as an American, though he carries a U.S. passport

It’s the same process every time he meets someone new: He is asked the question, “where are you from?” He opens Google Maps and points out the Northern Mariana Islands, the small archipelago in the middle of the Pacific Ocean that he calls home.

More questions always follow.

“Are you international?”

“Do you have internet?”

Malate usually sighs in resignation, then explains that the Northern Mariana Islands are part of the United States. He is American, just like his peers.

“I find it odd that we have to explain that I’m from a U.S. territory,” Malate said. He wishes that these territories and their relation to the United States were common knowledge.

Malate is one of 50,000 residents of the Northern Mariana Islands, which is one of the five territories the United States currently oversees. In Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands American Samoa, and the Mariana Islands, residents are considered American, but have no representatives in Congress and are not eligible to vote.

As a result, many of these residents report feeling left out of the democratic process. Northeastern University sophomore Nesanne Mae Tam, who grew up in the Northern Mariana Islands, is one of them.

“People in U.S. territories are just as affected as any other U.S. resident by the outcomes of these elections, but unfairly, we still have no say in what happens,” said Tam, who is a computer science and linguistics major. “All we can do is watch and hope for the best, which never feels like enough.”

Article II, Section 2 of the United States Constitution provides that “States shall appoint” their electors. But despite being regulated by the Constitution, U.S. territories, like Washington D.C., are not subject to the same rights as states.

In the early 1900s, a series of Supreme Court decisions, called the Insular Cases, granted the United States sovereignty over overseas territories, under the label of unincorporated territories, without requiring that they receive full constitutional rights.

In the 1901 case Downes v. Bidwell, Supreme Court Justice Henry Billings Brown ruled that U.S. territories are “inhabited by alien races, differing from us in religion, customs, laws, methods of taxation, and modes of thought, the administration of government and justice, according to Anglo-Saxon principles.”

Federal Appeals Court Judge Juan Torruella, in a commentary for the Harvard Law Review Forum, said the Insular Cases allowed citizens of these territories “to be treated unequally from those in the rest of the nation solely by reason of their geographical residence.”

Daniel Immerwahr, associate professor of history at Northwestern University, says that isolation from political involvement isn’t the only way the federal government treats territories differently.

“There are all kinds of ways in which [these territories] are deprived of political rights,” he said. “It’s not surprising to see that economic investment, or federal investment, in the colonies is far less than it is in the states.”

Immerwahr is the author of the book “How to Hide an Empire: A Short History of the Greater United States,” about the history of United States territories. Immerwahr spent months in the former territories of the Philippines, Hawaii and Alaska as well as the territory of Puerto Rico, studying about America’s influence on these places.

“It’s embarrassing,” he said. “People in the mainland really know too little about these peripheral spaces. These are spaces where around four million U.S. nationals live.”

While the consequences of ignoring U.S. territories are relatively low for people on the mainland, they can be dire for territory residents, Immerwahr said, particularly when natural disaster strikes. The U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico are still suffering from a lack of relief efforts by the federal government following Hurricane Maria. And Super Typhoon Yutu, which hit the Northern Mariana Islands last month received little to no mainstream news coverage.

“I think that these storms are crisis moments and exhibit both the longstanding neglect that these territories are suffering from,” said Immerwahr. “The problem isn’t just the weather, the problem is the lack of infrastructure and the lack of federal commitment.”

A 2017 federal report revealed that problems, including staff shortages and lack of trained staff, slowed Federal Emergency Management Agency’s response to Hurricane Maria.

Rep. Gregorio Sablan, a non-voting delegate from the Northern Mariana Islands to the U.S. House of Representatives was vocal in his criticism of FEMA’s delayed response.

“I am not satisfied with their work,” he said at a December hearing. “How can I be, when so many of the people I represent remain without power and water, living in shelters and tents, their children not in school, without jobs and income, struggling day by day?”

Although efforts to obtain voting rights for U.S. territories are underway, they aren’t making much progress. In November 2015, six former Illinois residents who moved to Guam, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, filed a lawsuit in Illinois’ northern district court after they were denied absentee ballots. Their case was lost the following year when the court ruled that former Illinois residents who live in territories do not have a right to cast absentee ballots in Illinois. The judge cited the Insular Cases stating that constitutional rights do not apply to territories.

Although the case, titled Segovia v. United States, was appealed to the Supreme Court in April 2018, the Supreme Court declined to review it.

“It was surreal to watch federal officials actually argue that residents of U.S. territories are not denied meaningful political participation in the federal government because they can vote in presidential primaries, can vote for a non-voting congressperson, or can move to one of the fifty states and vote there,” said Neil Weare, founder of the activist group Equally American, in a press release after the decision. “This kind of reasoning not only defies logic, but it insults the dignity of U.S. citizens living in the territories.”

Weare’s organization is also involved in the case of Fitisemanu v. United States, which challenges the Insular Cases and the federal law in the Nationality Act of 1940 that labels those born in America Samoa as U.S. nationals not citizens. The case is waiting to be reviewed.

“I think that it’s just that now, last few years has really been a lot to demonstrate how the deficiencies and injustices in federal territorial relationships,” said Weare. “I think that historically there has been some kind of window dressing that this is a benign thing or maybe even beneficial relationship.”

In the meantime, many territory residents are working to raise awareness through advocacy work and art.

Craig Santos Perez, who was born and raised in Guam, now uses his poetry to empower Pacific Island culture. Perez hopes to spread awareness of the impact that United States colonialism had on his territory. Lauded for his work, Perez has received awards from the Poetry Society of America and the Before Columbus Foundation for his poems about migrating from Guam to California as a child.

Perez says his poetry is a “powerful and emotional way to convey messages of decolonization, demilitarization, and cultural revitalization.” He hopes to educate the public about the territories and to fight for visibility.

“To many, the territories are completely invisible,” Perez said. “This, in turn, makes me feel invisible, and it makes me feel like my culture and homeland are insignificant.”

In a email interview in November, Rep. Sablan said he was looking forward to the Democratic Party’s majority in Congress. In previous years when the Democratic Party held majority, rules allowed the Resident Commissioner and Delegates from territories to vote as part of the Committee of the Whole, when bills are debated and amended before final action by the House.

“I look forward to a new House rules package including the restoration of our vote in the Committee of the Whole,” Congressman Sablan wrote. “Ultimately, however, we must all set our eyes beyond this limited and symbolic vote and decide that every citizen – no matter where in America they may live – must be fully represented in the House.”