By Hannah Bernstein & Jasmine Wu

Facebook

Twitter

Google-plus

Wordpress

Gloria Colon always knew where her roots originated. She was a First Nation, from the Elsipogtog reservation in Canada’s New Brunswick province. But after spending her childhood in Boston’s foster care system, she wasn’t sure how to connect to a part of her history she didn’t know much about.

“I was taken away when I was young, so I didn’t know what a drum was, I didn’t know what a rattle was,” she said, referring to certain Native musical instruments. “I was lost and I didn’t know who I was or wasn’t. Once everything fell into place, I was like, ‘Oh, okay. Now I know who I am.’”

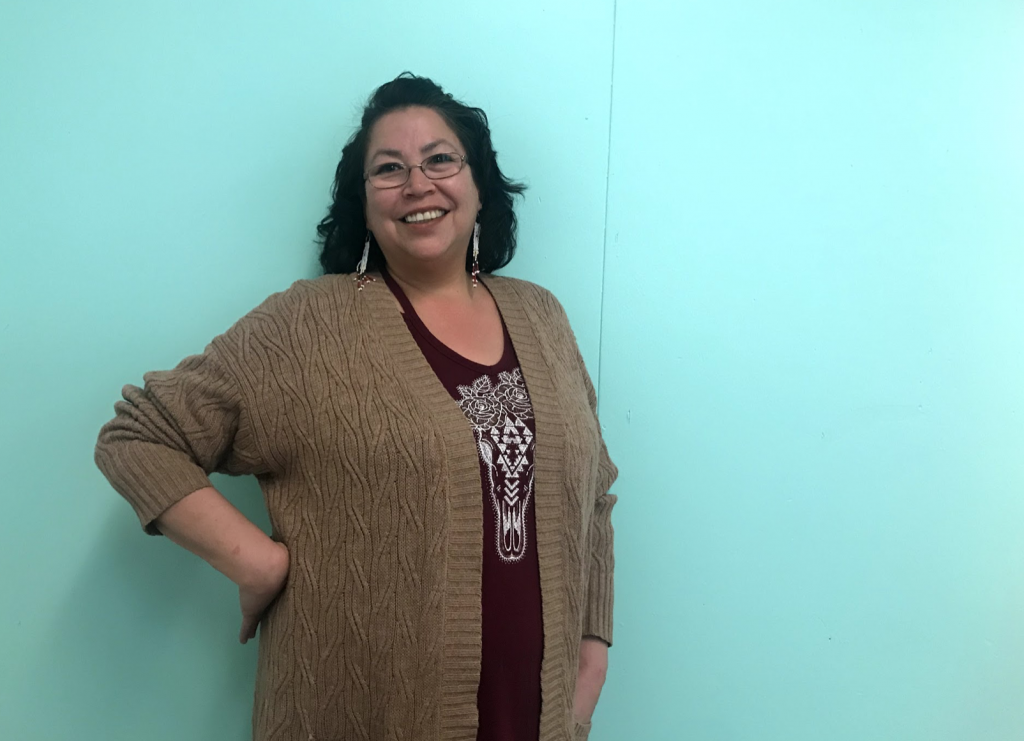

Everything came together once she began working at the Native American Indian Center of Boston, a nonprofit organization located in Mission Hill, in the early 2000s. She learned about cultural traditions of dancing, singing and artwork. Now, almost two decades later, Colon works as the center’s outreach coordinator — but said herself that she wears quite a few “hats” beyond that.

The center has a goal of closing the opportunity gap between indigenous and non-indigenous people in Boston, and offers seminars and workshops focused on things like computer skills. Colon teaches many of those classes herself.

Gloria Colon, outreach coordinator at the Native American Indian Center of Boston, has been working at the organization for almost two decades.

“We knew that it was needed, because obviously if you have a job, you have to learn [Microsoft] Word, you have to do PowerPoint,” Colon said. “You have to know your way around a computer in order to go forward.”

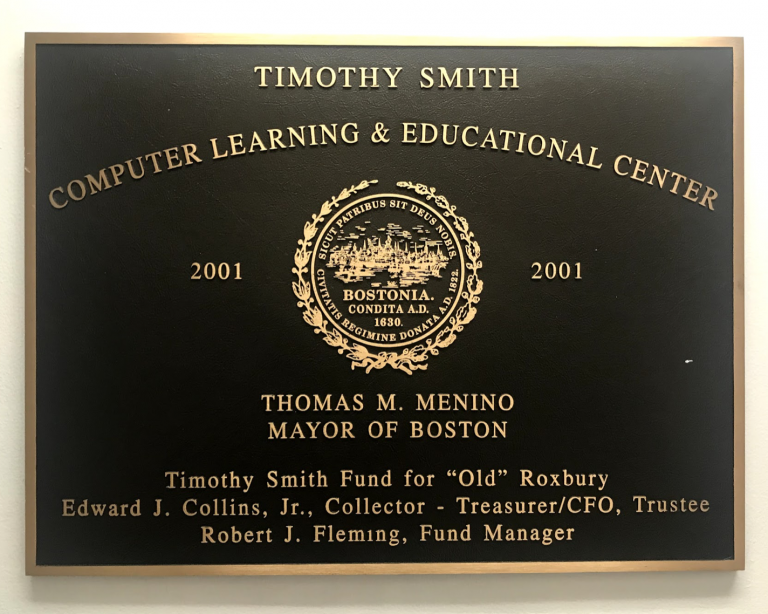

To provide access to technology for their members, the Native American Indian Center partners with the Timothy Smith Network, a Roxbury nonprofit that provides computer equipment for local community centers. Milton Irving, executive director of the Timothy Smith Network, said this technology helps to level the playing field for those in lower income communities.

“It’s around access. If we know that communities outside of the urban areas have access to programs that feed into pathways of higher education and employment, why shouldn’t these communities?” he asked.

He calls the mission at the Timothy Smith Network a “digital civil rights movement.”

Adreenne Law, director of programs at the Timothy Smith Network, said she has seen first-hand how the computer labs have helped those at the Native American center by learning hard skills such as resume writing and typing skills, and she’s seen tangible outcomes.

“There was definitely a number of students who were able to continue on with getting jobs, better jobs, and going on to college,” Law said.

Law said working with the center has even broadened her own cultural understanding of the Native community, since they view teaching as a two-way street.

The mission to preserve the history of indigenous people in Boston began more than 50 years ago with the Boston Indian Council. The organization bought its three-story brick house on South Huntington Avenue in 1969. The building provides office space for the organization’s employees, a large auditorium to hold events, classrooms full of toys and community rooms for meetings and programs.

After the city wanted to redevelop the land, the center had to negotiate to sign a 99-year lease on the actual building.

Back then, the purchase included an area of green space behind the building that they frequently used for community barbecues, powwows and summer camps. In 1991, the Boston Indian Council dissolved and reformed as the Native American Indian Center of Boston.

The center now has a 99-year lease on the building, once a women’s correctional facility, while the city of Boston to maintains ownership. The city built a large apartment complex on the green backyard space. It’s so close that the building’s interior is visible through the second-floor office windows.

Colon’s office is on the first floor, one door of many in a long hallway that used to be cells for prisoners. The walls are covered with Native artifacts, including dreamcatchers and traditional paintings, some of which were made by members or staff. Propped against the wall is a large, painted door that Colon designed herself for an event last year supporting murdered or missing indigenous women. She explains that it’s about rising above the effects of domestic violence and becoming free.

“When you do work at a nonprofit, you have to have a good heart,” Colon said. “You have to have that caring factor.”

Colon said the center demonstrated a caring factor last year during their annual community dinner, that they put on as a Thanksgiving alternative. When the attendees ended up with leftovers, Colon said they knew they couldn’t throw them out.

“We went across the street to the nursing home and we brought that to them,” Colon said. “They were so happy. They just loved that. So anytime we can try to help anybody, we look forward to doing that.”

The center’s executive director, Raquel Halsey, came to Boston from Maryland in 2012. It was a challenge, she said, because she often felt that Boston residents didn’t take Native issues into consideration or think about whose land they were living on. Those feelings pushed her to find a way to get involved with her own community, and she began volunteering at NAICOB in 2015.

“I haven’t been able to leave since,” she said. She took on the role of interim executive director in 2016 after serving some time on their board of directors. She said she wants her role to be interim because she believes someone with Native roots in Massachusetts should serve long-term.

The erasure of identity that Halsey feels is intimately tied to the history of Native Americans in Boston. According to The Pluralism Project, a Harvard University research project on religious history, tens of thousands of Native Americans were living in Massachusetts for more than 12,000 years before European traders arrived in 1616. Less than 40 years after their arrival, nine out of 10 indigenous people had died from European diseases.

Settlers in Massachusetts packed Natives into Indian Praying Towns in an effort to convert them to Christianity. Those who survived disease were likely involved in King Philip’s war, a final attempt by the Natives in 1675 to reclaim land after years of disputes. The two-year war was one of the bloodiest conflicts per capita in American history, according to the New England Historical Society.

Raquel Halsey, executive director of the Center, said many Boston residents haven’t taken Native issues into consideration or actively think about whose land they are living on.

The Massachusetts government granted indigenous people citizenship with the Enfranchisement Act of 1869. But Halsey says that didn’t change the long list of anti-Native laws, including one from 1675 which stated Native Americans were not allowed to enter Boston city limits. Although unenforced, that law was on the books until 2005, when it was repealed by the state legislature and then-governor Mitt Romney.

Halsey says that victory, a key memory for many members of the Native American Indian Center, is part of why she does what she does.

“I consider myself incredibly lucky to be able to work in a setting where I primarily serve people from my community, meaning the Native American community,” she said.

Colon agreed. “We’re all part of each other’s families. We’ve seen our children grow, good times, bad times,” she said. “It’s a family. Like a family, you have your good days, you have your bad days, but no matter what — you’re still there.”

##