Love in the time of coronavirus

Decisions need to be made before members of a couple (and members of both their households) can feel comfortable removing their masks and being in close proximity to one another. The social distancing effects of the pandemic might have altered the way people date, perhaps forever.

For many people, the past 11 months have represented a period of loneliness, isolation, and a loss of dating life. Even though vaccine distribution has begun, college-age singles who want to get back into the dating scene still have months to wait until they can get their dose.

“I feel like I’ve lost a year of my dating life,” said Hank Sparks, a senior at Harvard. “It’s not ideal at all. So it’s something I’m pretty upset about.”

Besides the fact that many people without partners are mourning the loss of almost a year’s worth of opportunities to connect with others, they are also suffering an acute lack of the benefits that such connection involves. Aline P. Zoldbrod, 73, who has spent the past 30 years counseling couples and singles through their sex and relationship woes, called the current dating situation “a very lonely state of affairs.”

“Most people would actually have, like a physical longing…Your self-esteem feels bad, you’re lonely, right?” Zoldbrod said. “And then you’re not getting these feel-good hormones and chemicals in your body, so it’s a double whammy.”

This prolonged deprivation can result in decisions that are less informed by public health guidance and more by unmet biological and psychological needs. People are facing the dilemma of whether to put themselves (and others) at risk to satisfy their need for intimacy, or fight against human nature in order to comply with social distancing guidelines. The result is a large-scale social experiment in real time, one that health professionals say is an exhibit of human creativity in response to a biologically event that hasn’t occurred for a century.

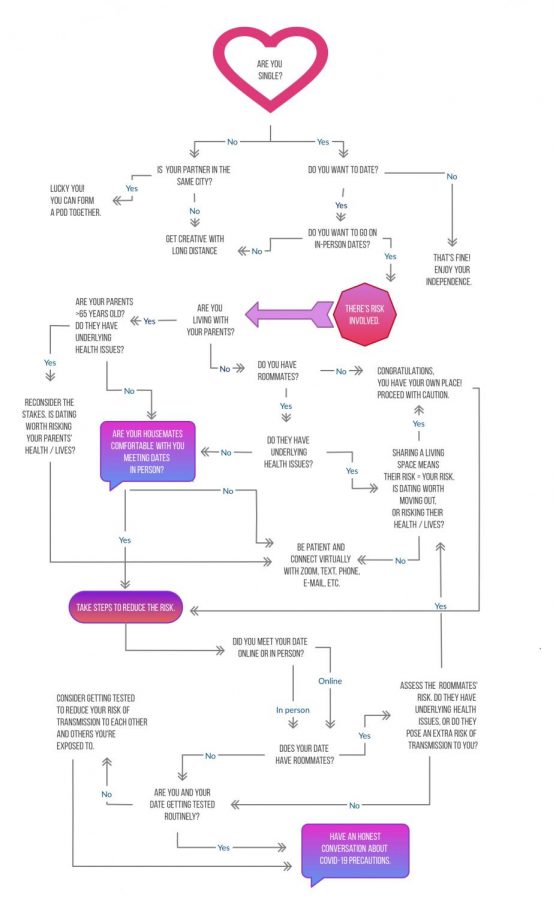

Many decisions need to be made before both members of a couple (along with members of both their households) can feel comfortable removing their masks and being in close proximity to one another. The social distancing effects of the coronavirus pandemic might have fundamentally altered the way people date, perhaps forever.

Feelings of isolation are particularly stressful to humans, with decidedly negative impacts on our mental, emotional and physical health. “Loneliness is a biological event in the body, and it’s associated with poor immune system functioning, poor cardiovascular functioning,” said Lisa Diamond, a professor of developmental and health psychology at the University of Utah.

Diamond, who is also a prolific author of books and studies investigating human sexuality and relationships, said that our brains and bodies have evolved against prolonged physical distancing. Oxytocin, a hormone associated with bonding, is released in response to physical proximity and contact. When that contact is denied, “that kind of feeling of loneliness is associated with a lot of negative physiological effects,” she said “And the only solution is human contact, human love.”

This drive, which Diamond said is a survival mechanism as hard-wired in our brain as the need for food, causes some young singles to risk potential exposure.

“It’s kind of like how people say that, like the safest way to have sex is to not have sex at all. With COVID, the safest, most foolproof way to not get COVID is to not leave the house,” 21-year-old Sydney Brown, a senior at Boston University said.“But I feel like there’s a point where you want this, like personal comfort,” Brown, who went on several dates over the summer when living in her parents’ home in Pittsburgh and in the fall after moving into college dorms in Boston, rationalized the risks she had taken. “I felt like I was doing as much as I could for my own, like to do my part,” she said, “But I feel like this has been such a long period of time; you get into different mindsets based on caseloads, based on how people are behaving around you.” After informing those she was living with of her plans for dating and communicating openly about safety precautions with the girls she met, Brown said, “I always felt like I was the safest of the people that I was around. So I didn’t really feel like I was doing anything wrong.”

To experts in human psychology, this sort of rationalization is not unexpected. “We’re just inherently social creatures,” Diamond said. “When you see other people breaking the rules, you feel like it’s more acceptable for you to break the rules.”

The tension between our social nature and desire to act independently is exemplified by a pandemic that, as Diamond said, “truly draws out the inherent connections among us all.” The virus does not act differently in response to our calculations of risk or assumptions of individual consequences for individual decisions. As Diamond said, “You may think you are taking the risk for yourself…but meanwhile, your risk has put someone you care about in great danger.”

Zoldbrod acknowledged the temptation to break social distancing rules is especially strong for young, healthy people. “I think people in [this] age group are not accustomed to thinking of death,” she said. “We all imagine that it’s the other person who’s going to get sick.”

Despite the dangers, for those who do break the rules, the potential payoff can be hard to resist. The conditions created by the pandemic can actually be beneficial to building strong relationships. At least for the moment, gone are the days of casual dating. The high stakes of a public health crisis necessitate an all-or-nothing approach to dating, forcing people to make decisions that they otherwise wouldn’t face in a new relationship.

21-year-old Liisa Balazs, who took a semester off from her studies at Northeastern University, connected with her boyfriend over the summer when she was staying with her parents in Stanford, Connecticut. The two met through mutual friends, and talked over text and Zoom before going on socially-distanced dates like hikes. Then, after just weeks of knowing one another, the two decided to move into Balazs’ 2-bedroom apartment in Boston.

According to Balazs, this drastic move was an efficient way of finding out whether they were right for each other. “It was almost an easy way to figure out if someone is worth it or not very quickly,” she said. “You’re not going to spend time putting in all this effort for someone that you don’t get along with, or don’t feel safe with, or isn’t respecting your boundaries.” Luckily for the fast-moving couple, the results of their high-stakes litmus test were positive. “Our communication was so good…I don’t foresee this being a short-term relationship at all, and neither does he.”

According to Diamond, the biological processes that cause us to crave and create human connection are sped up in stress-provoking situations like, for instance, a global pandemic. “The stress system and the attachment system are very intertwined in our brains,” she said. “It is having somebody alleviate your distress that bonds you.”

So for those who decide to shirk public health guidance in hopes of cultivating a physical and/or romantic connection, what is the best strategy for approaching these high-stakes decisions? For many, the answer lies in creating open communication and clear boundaries.

Emma Monahan, who is 24 years old and works full-time as a nanny, puts any potential partners through an extensive line of questioning.Monahan said she takes the situation extremely seriously because not doing so is not taking the proper precautions, “I constantly think of other people in the house, like I could potentially affect them. And that just makes me incredibly anxious.” In order to temper this anxiety, she asks the men she is considering meeting for a date about the precautions they take. “It’s like a common question to ask people now, if you meet up with them,” she said, laughing. “Not like, ‘oh how many siblings do you have?’ it’s more like, ‘are you healthy?’”

Asking how someone feels about the pandemic or wearing masks may actually be a good strategy for identifying whether or not they can be trusted to take appropriate health measures. Diamond said that this expression of an individual’s worldview lays bare their core value systems: “How do you receive and interpret scientific information, whether you put other people’s needs ahead of your own.” For those who don’t seem to take the pandemic seriously, she said this can be an indication that, “their immediate gratification is more important to them than the people that they love.”

Akram Semakula, who met his girlfriend before the COVID-19 outbreak and kept their long-distance relationship alive by using technology to communicate daily, says that they both decide which people and establishments to trust based on such conversations like, “When you talk to someone about COVID…the general sentiment they have about it: is it a global pandemic or like something that’s blown out of proportion?” The 21-year-old senior at Boston University said that responses to these sorts of questions, along with indicators like wearing a mask in more intimate spaces rather than immediately ripping it off, affect how he sees someone, and whether he trusts them to take the appropriate precautions in order for him to feel safe hanging out in person.

The big question that remains is the long-term effects these new social norms will have. Semakula predicts that the wariness toward others will remain after the pandemic has run its course, “People are gonna be way more conscious of who they’re interacting with on a day-to-day basis. People are gonna be more aware of who they want to date.”

Diamond hypothesized that unlearning the social distancing behaviors we’ve had to adopt will be a prolonged process. This extended period of heightened caution, which has forced many people to be more mindful of their everyday choices, could have wide ranging effects that cannot be fully anticipated. One outcome she postulated is that single people might feel more empowered to cut out short-term hookups that may not be altogether positive experiences.

Monahan followed a similar train of thought and said she thinks hook-up culture will definitely dwindle as people are more likely to be searching for a trusted companion and less apt to seek out short, impersonal connections. She said that the guys she matches with on dating apps these days, “seem more willing to get to know you…because everyone seems so lonely now with so much more free time.”

The safest course of action for everyone now is to abstain. For single people who feel lonely, Zoldbrod recommends keeping a journal and to “try and soothe yourself as much as you can with stuff that isn’t sexual and is safe, like talking to people you already know and trust.”

However, for those who can no longer handle their loneliness, Zoldbrod said that the best course of action is to proceed very carefully and really spend time interrogating and curating the people we allow into our space. “If you actually are lucky, if you really connect with someone, okay, it’s probably worth taking a risk.”

That said, she recommends investing in warm clothing, bundling up, and starting with outdoor dates where the risk is easier mitigated. “Get the best warm clothes you can get. Seriously, I would dress up in multiple layers and go for a walk outside.”